Author: Conner Moses

Advisor: Prof. Bhuvana Narasimhan

Class: LING 4220: Language and Mind

Semester: Fall 2022

LURA 2023

The purpose of the media’s reporting on world events is to inform and educate the public. What might not be expected or recognized is to what degree subtle linguistic cues can influence our perception and evaluation. As Boroditsky and Fausey (2009) describe in the context of legal cases and news articles, these cues can have a significant impact on people’s understanding and association of blame.

The research question of my paper looked at the example of how the American media has primed readers and viewers for certain narratives or viewpoints in the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I was prompted to consider this topic and question after reading The Media and the Gulf War: Framing, Priming, and the Spiral of Silence (Allen et. al, 1994). Allen et al. found, in the lead-up to the 1990 Gulf War, that media coverage was significantly more supportive of the U.S. government’s claims and actions than the general public was at the time. This had the effect of creating a narrative in the general discourse that was openly accepted by authority figures despite being not entirely true. Throughout the conflict, government spokespeople, as well as much of the mass media, employed language that “sanitized” the U.S.’s actions, emphasizing the precision that American technology brought to weaponry, with the erroneous implication that only intended targets would be hit, and that no innocent lives would be lost.

When considering linguistic cues in spoken or written media reporting, we can break them down into three categories. What I refer to as “emphasis” is largely a factor of message delivery — a media platform may choose to omit mention of the story or of particular facts, or it may bury the story on the back page, on the one extreme, or elect to run the story non-stop as front-page news on the other extreme.

The second category, which I’m calling “agency,” refers to the use of active or passive voice. Sentence structure using active voice can attribute blame or responsibility, while the use of passive voice can avoid any association, involvement or accountability. A sentence such as “The Russian army bombed the apartment building.” carries greater weight and assignment of responsibility than a sentence like “The building was hit with heavy bombardment.” Even more weight of responsibility can be achieved by attributing the action to a single person, such as, “Putin attacks over a dozen Ukrainian cities in ‘retaliation’ for bridge explosion.” (Yahoo News, 2022)

A third linguistic cue, which I refer to as “emotion,” is the use of language that is emotionally charged at one end of the spectrum or desensitized at the other. This is similar to a behavior noted by Loftus and Palmer (1974), where test subjects would watch films of automobile crashes and were more likely to remember higher speeds and more damage when questions were posed using words like “crashed” instead of “bumped.” Verbs like “slaughtered” carry much more emotional weight than “killed” or “lost”. In some cases, the suffering or loss of life may be glossed over or omitted with a verb like “fought”. Some justification of the violent action may be included with verbs like “responded.” The same military action can be characterized as “overthrowing,” connoting aggression and illegitimacy, or “freeing the country,” connoting justification. Adjectives and adverbs may be included to indicate culpability, such as “brutally,” “savagely,” or “unprovoked.” When reporting on the violent actions of the supported side in the conflict, the news report may resort to military terms that can minimize emotional response, such as referring to injury or loss of life as “casualties.”

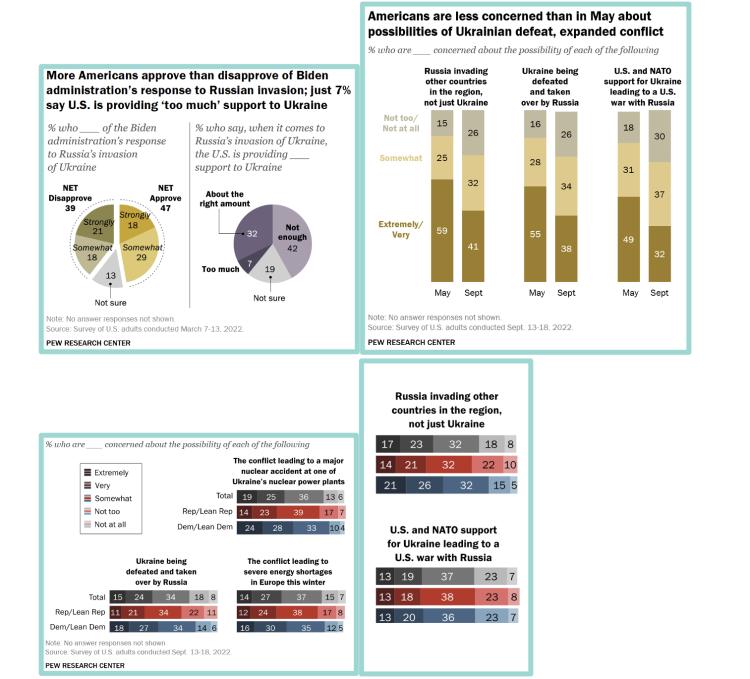

In my research paper, I suggested two ways in which the impact of these three types of linguistic cues might be assessed. My suggestions were (a) the use of polling data and (b) priming experiments. Polling data would be gathered and compared to media coverage categorized by support for aspects of the war. (Example polling data below.) The comparison would show if public opinion seems to follow the frequency and types of the above-mentioned linguistic cues that are employed in media coverage. The correlation would have to be assumed, which is a downside of this approach.

The second suggested approach was priming experiments. Participants with varying knowledge on the subject would be shown media coverage on the war that vary in the frequency and types of linguistic cues used (agency, emphasis, emotion). Their views on the war would be gathered before and after they read the coverage in order to see if the coverage may have influenced them. While I did not gather any data on these approaches, I propose that the suggested methodological approaches will yield valuable insights into the impact of language on the public’s perception of, and attitudes toward, war.

I believe it is in the public’s best interest to be able to identify these linguistic cues in media coverage and assess in what ways and to what degrees they affect our understanding of world events and our support of government actions. If we are aware of the effect that charged language can have, we are better able to decide for ourselves as to whether we agree with the positions subtly conveyed by the media.

Image Credit

REUTERS/Maksim Levin (found on: https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine)

References

-

Allen, B., et al. “The Media and the Gulf War: Framing, Priming, and the Spiral of Silence.” Polity, vol. 27, no. 2, Dec. 1994, pp. 255–84. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.2307/3235175.

-

Boroditsky, L., Fausey, C., & Long, B. (2009). “The role of language in eye-witness memory: Remembering who did it in English and Japanese.” Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 31. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4k31500t.

-

Loftus, E. & Palmer J., “Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory”, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, Volume 13, Issue 5, 1974, Pages 585-589, ISSN 0022-5371, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(74)80011-3.

-

“Putin Attacks over a Dozen Ukrainian Cities in ‘Retaliation’ for Bridge Explosion.” news.yahoo.com, news.yahoo.com/putin-attacks-over-dozen-ukrainian-231103555.html. Accessed 7 Dec. 2022.

-

Nadeem, R. (2022, April 1). Public expresses mixed views of U.S. response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine.Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy. Retrieved December 1, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/03/15/public-expresses-mixed-v...

-

Daniller, A., & Cerda, A. (2022, September 22). As war in Ukraine continues, Americans' concerns about it have lessened. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 1, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/22/as-war-in-ukraine-conti...

Conner Moses is majoring in Linguistics and is completing a certificate in Peace and Conflict Studies. He is interested in photography, politics, history, and the study of languages.

Conner Moses is majoring in Linguistics and is completing a certificate in Peace and Conflict Studies. He is interested in photography, politics, history, and the study of languages.