An Unforgettable Ride at the Ringwald Rodeo

A Conversation as Treasured as It Was Confounded

Why couldn’t we just call a halt for a while – stop making those chlorofluorocarbons that are destroying the ozone layer, halt the auto assembly lines and see if we can’t come up with viable alternative transportation, halt the arms production and the arms sales, maybe even consider ending wars? A radical thought, of course, but who knows? It just might work. What’s the point of all this hurrying, after all, if we can’t stop to smell the roses?

George Ringwald, former reporter at the Riverside Press-Enterprise, writing in 1991

An Unusually Sophisticated Inquiry by a Cub Reporter

I once had the great privilege of asking a Pulitzer-Prize-winning reporter a question that left him dumbfounded and speechless.

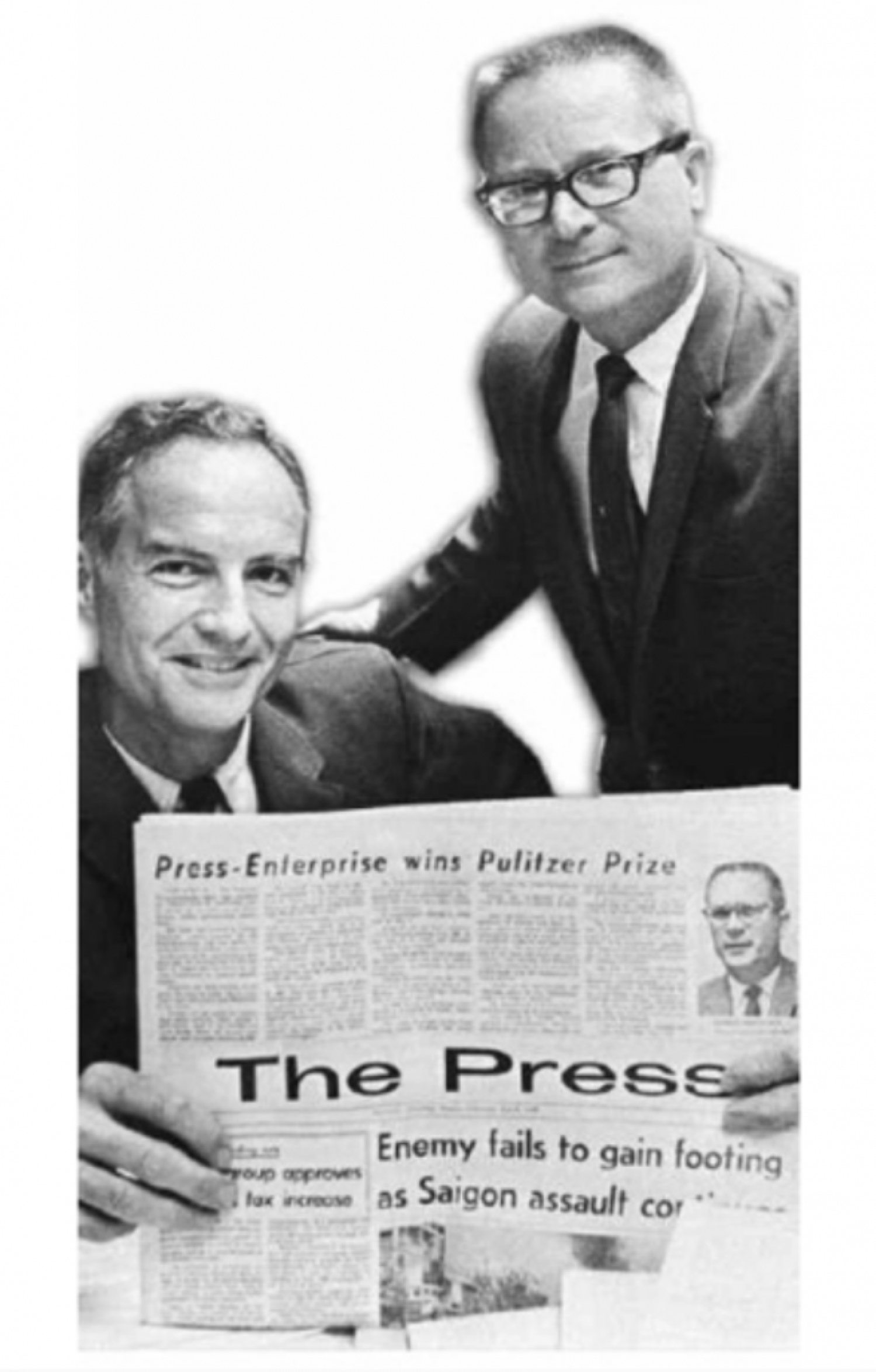

In 1968, I had an after-school job at the Press-Enterprise office in Banning, California. A reporter named George Ringwald had conducted a brave investigation of corruption in the administration and management of Indian lands in the Palm Springs area. His series won a Pulitzer Prize.

In those distant, analogue days of yore, Mr. Ringwald filed his stories by physically walking into our Banning office and placing his typed manuscripts in the big envelope that a courier picked up every day and drove to the main office in Riverside.

When Mr. Ringwald got the Pulitzer, I recognized him—rightly and accurately—as a rock star of accomplishment, a writer who had received national acclaim, who lived in my hometown, and who nonetheless walked among us mortals.

Even as we were congratulating Mr. Ringwald, the world was taking a turn toward calamity. Martin Luther King was assassinated. Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. Riots rocked many cities, and violent resistance to the Civil Rights Movement flared up. Commentators on national television news kept referring to these troubling events as “symptoms of a sick society.”

Sixteen-years-old, I was taking all this in, trying to get my bearings, and falling deeper and deeper into despair.

But I knew that our Pulitzer-Prize-winning reporter was going to appear in our office at some point. And I would be ready for him, prepared to ask him a very sophisticated question that would invite him to tell me what on earth was going wrong with our country.

Remember, Mr. Ringwald was an enormously accomplished writer, who was recognized nationally but who had somehow been consigned to live in the humble town of Banning.

So I couldn’t just ask him a plain, direct question.

On the contrary, I knew I had to craft the question so that it would sound very sophisticated and would thereby engage his powerful mind.

By the time Mr. Ringwald walked innocently into our office to file a story, I had designed a question that met those specifications.

Without suspecting an ambush, Mr. Ringwald said “Hello” to the cub reporter.

The cub reporter then said to him, “Mr. Ringwald, do you subscribe to the sick society syndrome?”

I had every reason to think that this was the right wording to address a Pulitzer-Prize winner.

“Subscribe” I knew to be a very sophisticated verb that meant “agree with” or “believe.” And I knew that pundits and commentators aplenty had been asking whether the assassinations and the violence in cities provided evidence for the diagnosis that we lived in a sick society. And “syndrome,” I felt, was the exactly right noun for pulling together the various “symptoms” of sickness that all the commentators and pundits kept bringing to our attention.

“Mr. Ringwald, do you subscribe to the sick society syndrome?”

Mr. Ringwald seemed to be surprisingly slow to grasp the excellence of this question. He sat down, paused, and looked very puzzled.

And now, to reveal the trap that I had unthinkingly set for this poor man, I will retype my question as he heard it.

“Mr. Ringwald, do you subscribe to The Sick Society Syndrome?”

So this was his befuddled response: “I’m not sure I’ve ever heard of that.”

I was flabbergasted. How could this very accomplished and very connected man have missed all those solemn reflections about the illness afflicting our society? How could it be that I, a sixteen-year-old bumpkin, was turning out to be so far ahead of a Pulitzer Prize winner when it came to keeping up with the times?

Eventually, we figured it out.

For good reason, Mr. Ringwald thought that I had learned of a new publication, The Sick Society Syndrome, recently launched to compete with Ramparts and Mother Jones, and now on a quest for subscribers.

Once we got our wires untangled, neither Mr. Ringwald nor I had sufficient energy left for assessing the symptoms plaguing our society.

But what had I wanted from Mr. Ringwald?

Fifty-two years later, I have a pretty good guess, though I offer this guess with appropriate caution. If, as historians often say, the past is another country, our minds as teenagers surely qualify as another planet.

But here’s what I probably wanted.

I wanted Mr. Ringwald to reassure me. I wanted him to tell me that I didn’t need to be so worried. I wanted him to say that, yes, he understood how the violence in the nation might make me think that things were falling apart, but as my wise, Pulitzer-Prize-winning elder, he could assure me that this was a bad phase that would not last.

And now, in 2020, I cannot tell you how much I wish that Mr. Ringwald would appear in my remote working locale and give me one more chance to ask for his guidance, this time with my sophisticated phrasing deleted, and plain English put in its place.

Turn-About May Be Fair Play, But That Doesn’t Make It Anything to Look Forward To

Exposed to a precariously high dosage of irony, I am now sometimes asked—every now and then, by a reporter— the very questions I wanted to ask Mr. Ringwald.

Millions of Americans are trying to figure out how worried they should be about the nation’s current state of division, disorder, and misfortune. Deep currents of perplexity have fed a hope among some that historians will swing into action as the professional counterparts of physicians.

To put this another way, might there be a chance that historians could diagnose the afflictions of societies as doctors diagnose the afflictions of individuals?

People who struggle with illness ask doctors, “How bad is it?”

In 2020, a surprising number of people seem equally inclined to ask historians, “How bad is it? Is our current concatenation of calamity unprecedented? Has the nation been this divided before?” Or, to put this in more sophisticated phrasing, “Do you as a historian subscribe to the sick society syndrome?”

Here’s my guess as to what drives the hope that historians can help.

When people seek out a historian to ask if the tensions and conflicts of our time are unprecedented, they are hoping for an answer along these lines: “In fact, the troubles in 2020 are very familiar to us. This nation has periodically come close to falling apart, divided by fractures and factions that make resurgences now and then. But those times pass, and then the nation turns out to be OK again. Yes, the United States seems to be falling apart right now, but history tells us that we’ll be returning to an even keel soon.”

But history tells us no such thing.

Back to the question: “How bad is it? Has it ever been worse?”

Asked that question on many occasions, I assembled an answer which I delivered in a manner that bore a certain resemblance to a vending machine dispensing its holdings:

In the mid-nineteenth century, with tensions mounting over the expansion of slavery into the West, and then with the Civil War itself, division went way beyond differences of opinion, attitude, conviction, and principle, and became actual, armed disunion. Moreover, there were innumerable incidents in the American past, ranging from the invasion and conquest of Indian homelands to the lynchings of African Americans and Mexicans, when astonishing brutality and violence figured as dimensions of everyday life. No, the antagonisms and currents of hostility in our time are far from unprecedented. And, yes, you could make the case that things have been worse.

And, after many recitations of this answer, I have lost patience with it.

When I declared that American history comes well-supplied with episodes when every variety of hatred and hostility had free reign, what sort of comfort or consolation did I think I was offering? Was I guided by some witless idea that facing up to the miseries and calamities of the past would buy us a license to dismiss the seriousness of our troubles today?

Even though our nation’s history has been a kaleidoscope of tensions and divisions, our current constellation of problems today is nonetheless unparalleled and unprecedented.

We struggle against a virus that devastates and destroys individual lives, and we have no vaccine or treatment in our reach. We have reached a striking level of civil unrest, bringing into full view the lasting injuries and injustices that appear everywhere we look in the arena of American race relations. We have a tottering economy, with a massive number of unemployed workers—as well as owners of small businesses—in dire situations. And we could not, as a people, find our way out of a paper bag if such a modest undertaking required mutual respect and reasoned deliberation.

This posed a question that I cannot answer: how is the recognition of tragedy in the past supposed to make us feel better about the present?

Reminiscing about George Ringwald as a Way to Feel Better about the Past and the Present

Mr. Ringwald died in 2005 at age 81. Two years after his death, the Riverside Press-Enterprise ran a story about his character and his achievements. In the article, his friends settled on three words to describe him: “Dogged. Joyous. Curious.”

The influential series that Mr. Ringwald wrote (and filed in the courier’s envelope right next to my desk) “expos[ed] how judges and attorneys had been using their positions to levy exorbitant fees against the estates of the Agua Caliente Indians of Palm Springs.” Besides winning the Pulitzer Prize, Mr. Ringwald’s investigations “led to a change in the laws governing the administration of the Indian estates.”

The timing—of telling you about Mr. Ringwald, his achievements, and our confounded conversation about sick societies—is now looking utterly providential.

I started an outline for this essay just before the Supreme Court issued the decision (written by the Colorado-originating Justice Neil Gorsuch) in McGirt v. Oklahoma, affirming the promises made in the treaty with the Muscogee after their relocation from the Southeast. And now I am finishing this essay two days after the announcement that the Washington “Redskins” will change their name.

Dead for fifteen years, Mr. Ringwald, suddenly seems very present.

And now, ready for this?

Before serving in World War Two, Mr. Ringwald graduated from Colorado State University.

While I would have been proud to learn he was a Buff, I am completely content to share my association with Mr. Ringwald with my many beloved colleagues at CSU, and with Cam the Ram.

If we direct our thoughts to our legacy from our one-time fellow Coloradan George Ringwald and to the work he did on behalf of restoring justice to Indian people, our society starts showing some significant signs of health.

“Tomorrow is a new day with no mistakes in it yet.”

The words of Lucy Montgomery (whoever that is), appearing on a magnet on the Limerick household refrigerator.

If you find this blog contains ideas worth sharing with friends, please forward this link to them. If you are reading this for the first time, join our EMAIL LIST to receive the Not my First Rodeo blog every Friday.

Photo Credits: A prized day in P-E history photo courtesy of the Press-Enterprise.