Sandy Greenhills West, Urbana Asphalt West, and Suburbia Greenlawn West Take a Family Trip Through Time

Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic, but destroy our farms, and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.

William Jennings Bryan, “Cross of Gold Speech,” 1896

William Jennings Bryan’s rhetoric may be overwrought, but he makes a point that’s still worth considering.

Patty Limerick, “Not My First Rodeo,” 2020

The rural/urban divide runs through every region of the nation: the Northeast, the Mid-Atlantic, the South, the Midwest, and various subregions of the West. Residents in every community in the nation stand in some relationship to the divide.

Even a small step toward clarity in thinking about the rural/urban divide—its origins, its evolution, its current configuration, and its susceptibility to gestures and overtures of good will—could make a big difference. Since every region struggles with this divide, taking this small step could have an impact nationwide.

Here’s the good news: languishing in our storage cabinet for intellectual property, the Center of the American West has everything needed to take this small step. In the 1990s and the early 2000s, we performed a pubic program called the “Urban/Rural Divorce.” Taken to communities from Rock Springs, Wyoming to Boise, Idaho, from Idalia, Colorado, to Vancouver, Washington, this program worked.

And what do I mean by “worked”?

The program provided an effective framework for exploring the tensions and resentments—as well as the alliances and collaborations—between rural places and urban places. It created a forum that gave expression to the intense anger that some populations in the rural West felt toward cities, while it also put a light on the obliviousness to that anger that prevailed among many urbanites and suburbanites. And, maybe most valuable of all, this program used humor as the WD-40 for addressing and easing tension, achieving a seemingly impossible merging of the serious and the comical.

In the early 2000s, I and my coworkers responded to the success of this program in a decidedly peculiar way. Having crafted and field-tested an effective way to host deliberations on the rural/urban divide, we quit performing the program and stored the records it had generated in rarely opened filed cabinets.

And yet, even as we consigned our program to years in storage, the rural/urban divide grew wider, rural resentment gained strength, urban obliviousness made a resurgence, and the need for our program became ever more urgent.

In the presidential election year of 2016, herds of commentators and pundits could not stop talking (not that they tried!) about the rural/urban divide as a central—perhaps the central—structure of political polarization and antagonism. And, at that point, the possibility of reviving our dormant program started to gain ground.

Given that the relevance of this program has expanded dramatically, why haven’t we just rescued it from the intellectual-property storage cabinet, dusted it off, replaced its run-down batteries, and sent it back out on the road?

Good question.

A New Approach to an Old Problem Hits the Road

In 1993, writer Ed Quillen published a memorable essay in the influential regional periodical, High Country News. Since Quillen was one of the liveliest thinkers ever to explore and contemplate the American West, he was quite the production center of certifiably memorable essays. But his 1993 publication stands on its own as a reminder that we forget Ed Quillen to our peril. (Having written that remark and decided to let it stand, I will now say the obvious: no one who knew Ed Quillen will ever be at the slightest risk of forgetting him!)

But before I offer a quick summary of his essay, we have to take a quick trip to the distant past.

The history of the relationship between what we now call the Rural West and the Urban West goes back for a millennium or two. In North America, some indigenous groups clustered in towns and cities, while other groups moved in a seasonal cycle through landscapes they knew well. Trade, and sometimes hostility, set the terms of a dynamic relationship between these differing ways of being at home in this area.

In the nineteenth century, the invasion of Euro-American settlers disrupted these established ways of life. Driven by a quest for resources, participants in resource rushes usually paired rural development and urban development. People yearning to take possession of minerals and land dispersed into remote places, and merchants and town founders responded fast to the opportunities—and the markets—that these migrations created. In early phases of Euro-American settlement, rural people and urban people were, to use a term of our times, “co-dependent,” sometimes in fairly congenial or at least reciprocally tolerant ways.

And now, after that massively over-generalized paragraph, we will leap over a century and a half, with a nimbleness rarely permitted to historians, and return to Ed Quillen.

The title of his 1993 essay offered its own effective summary of Quillen’s unsettling argument: “Now That Denver Has Abdicated . . . Who Will Coordinate and Inspire the West?” With precision and erudition, he traced the many transactions that once tied Denver to its rural hinterland. He then went on to trace the fraying—really, the disintegration—of the belief that Denver’s well-being rested on the well-being of the rest of the State.

And here is the statement that, over several years. redirected my professional life:

Denver and its hinterland are a couple who were once intimate; each provided for the other and supported the other. Now they appear to be going their separate ways. Instead of cooperating, they compete.

In 1993, my emergence as a public intellectual had become an explosion of opportunity. Public speaking gave me an enviable chance to get to know people all around the state. I made frequent ventures to the Western Slope, to Southern Colorado, to the Northern Front Range, and to the Eastern Plains. At the same time, I got to know at least a small sector of the people we might call “the Denver elite.”

On multiple occasions of meeting Coloradans and hearing their stories and perspectives, I was participating in a social process that I could characterize as “drinking through a firehose,” though that phrase attributes a quality of discomfort to what was actually a delightful round of socializing.

But as I traveled hither and thither, there was one element of discomfort: what I heard from people in Denver and what I heard from people in the other areas of Colorado constantly brought to mind Ed Quillen’s observation. The perspective I heard in Denver and the perspective I heard in other locales did indeed match up with the analogy of a couple headed toward separation.

What could I do to help?

I could take advantage of the fact that I am the only person who hangs around in public policy circles, whose thinking was shaped by classes in renaissance and reformation history. (Thank you, Professor William Hitchcock; you are no longer with us on the planet, but you had a lasting effect on the programs of the Center of the American West.)

In those classes, I learned about the vanished tradition of “the morality play.” The Oxford Languages website offers a crystal-clear definition of this genre:

Morality play: a kind of drama with personified abstract qualities as the main characters and presenting a lesson about good conduct and character, popular in the 15th and early 16th century.

In plays of this sort, living human beings lend their life force to the project of standing in for, representing, and embodying concepts or groups that would not otherwise be able to appear as compelling and coherent presences.

If this art form appealed to people five hundred years ago, then maybe it was time for a “retro” repurposing.

As soon as I conjured up this idea, Bill Hornby, the editor of the Denver Post, pitched into the cause by writing up an inventory of the points of contention between rural Colorado and urban Colorado. Neither I nor Bill nor Ed Quillen, who I soon drew into this cabal, had even a remote qualification as playwrights. But if we had a list of “points of contention,” we could take it from there

And so the program we called “The Urban/Rural Divorce” began its travels around the West.

In play, Sandy Greenhills West sued Urbana Asphalt West for divorce, presenting—at length!—his grievances and complaints. Urbana contested the divorce, though, awkwardly, she was forced to admit that she had sometimes forgotten that there was a marriage in place, since “Sandy was a quiet kind of fellow, and worked outside a lot.”

In communities that agreed to host us, we would enlist a local person as the judge, and we would also recruit local people to testify as character witnesses for Sandy and Urbana. When we performed in rural areas, we soon figured out that it would be smart to add a moment of “debriefing” to the end of our program: if I did not get the chance to tell the audience that I was playing a part and did not personally espouse Urbana’s opinions, I would have no one to talk to at the post-event receptions, while Sandy would be surrounded by comrades.

But it became increasingly clear that someone was missing from our entourage.

Sandy would reliably accuse Urbana of expansion and encroachment on his territory. Since urban boundaries were quite well-established and the era of urban annexation had petered out, this accusation did not make much sense. And yet Sandy was right in thinking that residential, and sometimes commercial, expansion was reshaping many areas in the West.

So who were we missing?

Suburbia! (Or, when a young man played the part, Subbie.)

So we added Suburbia, and we settled into our program: Sandy presented his grievances; Suburbia drank everyone’s water (including the Judge’s); and Urbana had to listen to and respond to complaints that she’d never heard before or had forgotten right after she heard them.

[As to who “we” were, a number of good souls rotated in and out of the role of “Sandy” and of “Suburbia.” They all met the definition of the word “troupers” (in Merriam-Webster’s absolutely accurate definition, “people who deal with and persist through difficulty or hardship without complaint”), and I am forever in their debt. You will see two of these good souls—Charles Scoggin and Tamar Scoggin, in a photograph at the end of this posting.]

From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, the troupers and I traveled hither and thither: to Rock Springs, Wyoming; Bend, Oregon; Boise, Idaho; Vancouver, Washington; the Elko Cowboy Gathering; to many sites in Colorado–Salida (where Ed Quillen served as an expert witness!), Gunnison, Telluride, Idalia, Montrose, Denver, to the conferences of the Colorado Municipal League and Colorado Counties, Inc.

We had adventures beyond recounting.

Boarding the plane to Spokane for a performance in Moscow, Idaho, we were asked by a flight attendant, “Are you traveling together?” “Oh, yes, we are!” we responded cheerfully. “But we’re traveling to get divorced; we could tell you a little more about this if you’d like to hear!” For some reason, the flight attendant chose not to pursue the conversation, and quickly directed us to our adjoining seats.

In Telluride, we were tested as never before on our ability to stick with the program of staying within our assigned characters, as real actors are supposed to do. The cascade of wildness began when Urbana said that Sandy could and should quit denying his paternity of Suburbia, since the kinship between them—in their defiance of regulation and claims of independence—was unmistakable. “We don’t need a DNA test,” I–or, rather, Urbana— said. But that remark brought the bailiff—played by the Libertarian Sheriff of San Miguel County—to life. “Let’s have a DNA test!” the sheriff exclaimed, as he escorted Sandy Greenhills West out of the courtroom for a tissue sample. Order was restored not long after this, but I was a long time gaining control of a fit of laughter that, really, only the most skilled of actresses could have suppressed. Fortunately, I hit on the strategy of disguising the laughter as sobbing, choking out the observation that it was very sad to see that Sandy was so out-of-touch with reality that he could not recognize his own daughter without a DNA test.

And now, by main force, I am calling a halt to reminiscing, and moving on to summarize the usual content of the verdicts delivered by our multiple local juries: Suburbia was remanded for a Tough Love or Outward Bound program for character improvement, while Sandy and Urbana were told that their marriage would not be dissolved, though they would be required to take up rigorous methods of birth control on behalf of population limitation.

Anyone reviewing our old script would have to be impressed by how much we packed into a short time. We argued about water; agriculture; mining; the disconnect between Sandy’s production and Urbana and Suburbia’s consumption; excessive government regulation and unfunded mandates; our feelings about our “Uncle Sam,” especially in the allocation of his money; the threat that big box stores posed to “mom and pop” businesses; the condescension that second homeowners, outdoor recreation enthusiasts, and tourists often showed to local people; the dignity of physical labor; the persistent mythology attached to cowboys; the limitations of rural health care; the similarities and differences in rural, urban, and suburban dependence on automobiles; the negative stereotyping of rural people by urban people; the equally negative stereotyping of urban people by rural people; and the inequities of internet access to rural communities.

We covered a lot.

When we gave our presentation in small towns, nearly all the time we found that our audience was already familiar with all these topics, though they still appreciated the way our peculiar form of presentation brought these issues to life.

But when we gave our presentation in cities, audience members often said to us, “We had no idea that rural people had these concerns.”

We never had the chance to say, “Our work here is done.” Because it wasn’t.

So why on earth did we put this vital program into storage?

I’m getting to that.

Rescue by Revision

The program petered out because we had saddled ourselves with an unwieldy operating mode. Before any communities—even the ones who needed us most—could host our program, three of us had to coordinate our schedules and travel together.

There had to be a better way.

Our script for the “Urban/Rural Divorce” still carries overwhelming relevance. By 2016, there was no mistaking the fact that the time had come to get it back in the world. But it needed a major remodel.

In 2018, we got started. Jake Rothman, a gifted young man from Crested Butte with a history degree from Colorado College, came on board at the Center to get us moving.

Excavated from its long period of storage, the script needed rehab. Badly.

Jake identified the areas where the script most pathetically showed its age. He removed the cobwebs from the references to digital technology and to popular culture. And he worked the whole script over to change the venue—from a courtroom where a judge presided over a divorce trial, to an office where a therapist conducted a last-ditch counseling session. Jake also gave Suburbia the right to grow up. With the passage of fifteen years, the one-time self-preoccupied, self-centered teenager now had the potential for being the most sensible member of her disordered family.

Jake also added issues that, in our first run of this show, we had either not noticed or had purposefully tried to evade. Clashing attitudes toward immigrants; intractable disagreement over gun control; troubling rates of depression and suicide in rural areas; layers and layers of meaning beneath the surface of conventional definitions of manhood and womanhood; epidemics of opioid and methamphetamine abuse; and a variety of manifestations of climate change (also known as drought, flood, and wildlands fire). With all these additional topics, Jake added intensity and weightiness to the script. But sticking with the format of a morality play, we could still offset the weightiness with a lightness of spirit, retaining room for the play of humor.

Just as important as the transformation of the script was the redesign of the operating system that would bring this new script into the world. The plan now is to prepare a kit: the revised version of the script; a video of me and two lucky people, as yet unidentified, who will play Sandy and Suburbia performing this new script; and a set of suggestions on how to adapt the program to capitalize on the issues that matter most to a particular locale; and guidance on how to recruit and select volunteers to perform the drama—and to watch it and discuss it. With this kit in hand, a civic group, a high school class, a church-affiliated volunteer organization, a city council or county commission, or, for that matter, a local theater group could go to town and declare, with the assurance that they were investing effort in a worthwhile cause, that “the show must go on.”

Readers, Here’s Where You Come In

From all reports, the pandemic has made puzzles very popular. So, for any reader wrestling with the emptiness and ennui that remote working and social distancing can produce here’s your chance to take on a consequential puzzle.

On many occasions, the Center of the American West has put forward the proposition that historians are the necessary craftspeople when it comes to the crucial human enterprise of tradition-sorting. Historians, this form of professional cheerleading proposes, are positioned to guide people in assessing their customs, habits, and traditions, by asking 1) what worked and deserves keeping? 2) what didn’t work and deserves to be modified or discarded? And 3) what should be kept on on the chance that a vision might appear for making it work in the future?

As every historian who has ever tried to execute this program has learned, it is a lot easier to exhort others to sort thoughtfully and wisely through a tradition than to perform this act by oneself.

So put on your thinking caps, whatever hat-gear is your preference: baseball caps, cowboy hats, red MAGA caps; or whatever city folks prefer to put on your heads (not to stereotype, but perhaps fedoras and berets?).

Rewriting as a Practical Exercise in Problem-Solving

The context of our Rural/Urban Divide program has been transformed by the pandemic, by the economic depression, and by the accelerated division and polarization of the Trump Era. Updating a script that had languished for years was never an easy task. But in the autumn of 2020, the difficulty of updating this script—or, really, updating anything else in our lives—has expanded beyond estimation.

But to return to the point: the relevance of this program has not diminished in the least. So it really must be updated.

Puzzle #1

How to Acknowledge the Steep Decline in Civility and Respectful Disagreement

When we put this play together in the mid-1990s, we thought the tensions in the nation were at a high pitch. We thought that the diminished capacity of citizens to engage in productive civic dialogue showed few signs of recovery or redemption. It seemed to us that rural Americans, urban Americans, and suburban Americans had become mysteries and ciphers to each other.

Little did we know of what was ahead.

So how should the script incorporate a recognition of the worsened condition of communication across the canyons of disagreement?

Here’s my first run at an updating and rewrite.

When Sandy, Urbana, and Suburbia arrive at the Counselor’s office, they are surprised to find that the Counselor has collapsed in despair and cannot even pull herself together to greet them. Even though Sandy, Urbana, and Suburbia are only symbols, they still have a streak of genuine compassion and kindness.

So they ask the Counselor what’s wrong.

The Counselor is weeping and has a hard time speaking for a moment. But then she manages to say that she has spent her career trying to help people communicate, and the state of the nation has convinced her that she and her colleagues in counseling have gotten nowhere and had an infinitesimal impact on the nation. She had already been feeling very sad, but then she watched the Presidential Debate on September 29. She had to sit, immobilized and desperate, as poor Chris Wallace pled with the President to stop interrupting his rival every few seconds. And she also saw his rival, every now and then, take the bait and respond in kind with insult and contempt.

After enduring that debate, the Counselor is ready to throw in the towel. She figures that what she saw in the presidential debate will be reenacted in her office, and her three visitors (and, indeed, all her clients in the near future) will devote themselves to shouting without restraint and making every effort to drown each other out. And she will be stuck in Chris Wallace’s miserable role, pleading with her participants to engage in “open discussion,” and to abandon their reciprocal refusal to listen and to embrace mutually assured vexation.

So she has spent the day on websites in search of an occupation she could take up for a mid-career shift. She’s always liked making pottery—maybe with people at home more, there’s a growing market for charming ceramics? People have always told her she has a soothing voice; maybe she could start a product line of recordings for agitated people to listen to when they need help getting to sleep?

Here’s the upshot.

Sandy, Urbana, and Suburbia must begin their counseling session with a goodhearted effort to persuade their Counselor not to give up. They remind her that when they traveled around the West together, fifteen years ago, they were part of a program with a firm commitment to making sure that conflicting viewpoints got a fair hearing. In those travels, they certainly argued, sometimes ferociously, but they never once talked over each other. So, really, Sandy, Urbana, and Suburbia assure the Counselor, they have proven themselves to be willing practitioners of the kind of civil exchange that has vanished from so much of public life.

Later on, they begin to wonder if the Counselor staged this scene of pretended despair in order to bring out the best in her clients.

As the session ends, Sandy, Urbana, Suburbia, and the Counselor co-author a public letter to the growing multitudes of the failed moderators of electoral candidate debates, offering those moderators useful guidance on how they can hold their ground and insist on behavior that will require the debate participants to set a model for their fellow citizens, and not embarrass the nation.

Puzzle #2

The Moment and Momentum of Masking: Suburbia Comes Of Age

By the time the revised script goes out into the world, vaccinations may have prevailed over the coronavirus and the pandemic will be over.

Maybe.

But for now, let’s assume that, even if vaccines are widely available, the current widespread distrust over their safety has continued, and the question—to wear a mask or not to wear a mask—is still a matter of fierce contestation between the rural West and the urban and suburban West.

And now back to my trial run at rewriting the script for 2020.

When Sandy, Urbana, and Suburbia enter the Counselor’s office, Urbana and Suburbia are masked and compliant with pandemic protocol. But Sandy is not masked, and he reaches out to shake the Counselor’s hand, all the time exhaling and inhaling without impediment. Urbana and Suburbia, though muffled, audibly gasp at this risky move.

It seems certain that the threesome will soon pitch into the familiar battle of 2020, in which coverings placed over noses and mouths—or the absence of those coverings—have come to deliver a concise and clear declaration of political identity and to organize and orchestrate rage and resentment.

Here the script takes an unexpected turn.

Remember that Sandy and Urbana are the co-parents of Suburbia, and that a key feature of the revised script is that Suburbia has grown up and is revealing a heretofore under-developed capacity for self-examination and for recognizing her responsibility.

So when the fight over masks heats up, Suburbia comes into her own.

“Dad,” she says to Sandy, “I am worried about you. When we traveled around in that divorce trial fifteen years ago, one of the things we always talked about was the crisis in rural health, with the closing of hospitals and the vulnerability of rural people dealing with serious illness when the medical experts they need to see are way beyond their geographical reach. That situation hasn’t improved over the last twenty years. So when you refuse to wear a mask, I get even more worried about your susceptibility to a real affliction—and maybe an avoidable one. I am not telling you to do anything you don’t want to do, but I am just telling you that I was already worried about the unfair situation you face with access to health care. And now, when you keep saying that Covid-19 is probably a hoax, and you won’t submit to tyranny by wearing a mask, the main thing you accomplish is that those of us who care about you get even more worried about what kind of medical care you’re going to have to settle for, if this virus gets a hold on you.”

Will this plea melt Sandy’s heart, and persuade him to put a mask on his face?

Probably not, but it seems like a better alternative than the usual fight.

One More Puzzle, This Time Involving a Pre-Existing Condition:

Sandy’s, Urbana’s, and Suburbia’s Concealed Complexity in the Old Script

When our troupe traveled the West in our first run of this show, we could never fully dismiss a burdensome thought: in our earnest effort to improve understanding and empathy, were we inadvertently confirming old stereotypes of both urbanites, suburbanites, and rural residents? Were we doing enough—really, were we doing much at all—to capture the variation of ethnicity, race, class, income, and occupation in rural areas? In urban areas? In suburban areas?

Probably not.

Through the old script, Sandy portrayed himself as a rancher or farmer, maybe a miner or logger. True, he would sometimes speak of the resentment that rural people working in ski resorts or tourist attractions felt toward urban and suburban visitors. But Sandy did not present himself as a small-town merchant or a restaurant owner. He certainly never spoke as one of the many federal employees, often born and raised in the West, working for land management agencies and fully committed to thinking of the rural West as their home. Telecommuters, enthusiastic converts to the exurban life, owners of second homes who genuinely care about the communities they live in could not, in the framework of the old script, claim even a marginal identity as rural Westerners.

In a very similar way, the characters of Urbana and Suburbia obscured variation in ethnicity, race, class, income, and occupation. As the targets of Sandy’s resentment, Urbana and Suburbia stood for the Westerners who lived in cushioned comfort and who, consciously or not, wielded power over the rural areas.

That characterization left the majority of urban and suburban people offstage.

How could we update the five-hundred-year-old form of the morality play to capture—or at least to hint at—this diversity within each of our three characters?

Here’s my best shot at a solution.

Near the end of the script, the last-ditch marriage Counselor pushes so hard that she finally reaches Sandy and Urbana. As she pressures them into self-examination, they break down, and unleash the confusion they have concealed from others and concealed from themselves.

“I don’t know who I am anymore,” Sandy admits. “I’ve presented myself a rancher or farmer who lives on and knows the land and who produces the food that supplies Urbana and Suburbia. But maybe I’m actually a maintenance man at a ski resort! Or a ranger at a National Forest! Or a banker or a car repairman or a wildlands firefighter or a snowplow operator! What would be wrong with that? Am I really prohibited from revealing the many dimensions of who I am?”

With Sandy bravely leading the way in honest reflection, the Counselor pushes Urbana and Suburbia to offer similar acknowledgments of the many dimensions of their identity.

“All three of you,” the Counselor says to them, “are plagued by stereotypes that simplify you and constrain you. And—here’s the core of your conflicts—you impose and inflict those simplifications and constraints on each other. Those stereotypes conceal you from each other like veils that you think you can’t throw off. But you can throw those veils off. In fact, you can set each other free from those constraints. Sandy, Urbana, and Suburbia: you have many dimensions, and together, you compose the kinship that we know as ‘the West.’”

That has turned out to be quite a forceful Counselor, especially when we remember that she started this session in a state of personal collapse.

Handing the Baton to the Young

Here are the words that Jake Rothman, our youthful collaborator, wrote for the Counselor to say to Sandy and Urbana:

No matter how bad things between you two are, you are stuck together. Like it or not, and in spite of this big, globalized world, you two still rely on each other for so much. . . Splitting up would be a lot tougher than just living with this marriage because you share so much. In my professional experience, I’ve observed that often couples learn more about each other and are able to understand each other’s viewpoints, even as they are in the process of trying to separate. It’s extremely important that you both understand this.

And here are the words that Jake wrote for the Counselor to say to the audience attending the pubic program:

All these characters have been symbols. Fortunately, you are actual people and not strictly defined representations. You don’t need a public therapy session to talk things out.

The circumstances of 2020 seem to call for a modification of only one part of Jake’s draft.

We know now that “actual people” do “need a public therapy session to talk things out.”

I hope that our script for the “Last-Ditch Mental Health Counseling Session,” revised with Jake’s help, will offer that opportunity to the nation as a whole to clarify the terms of the rural/urban divide and open a route to coexistence with a one-of-a-kind invitation to mutual understanding.

If you find this blog contains ideas worth sharing with friends, please forward this link to them. If you are reading this for the first time, join our EMAIL LIST to receive the Not my First Rodeo blog every Friday.

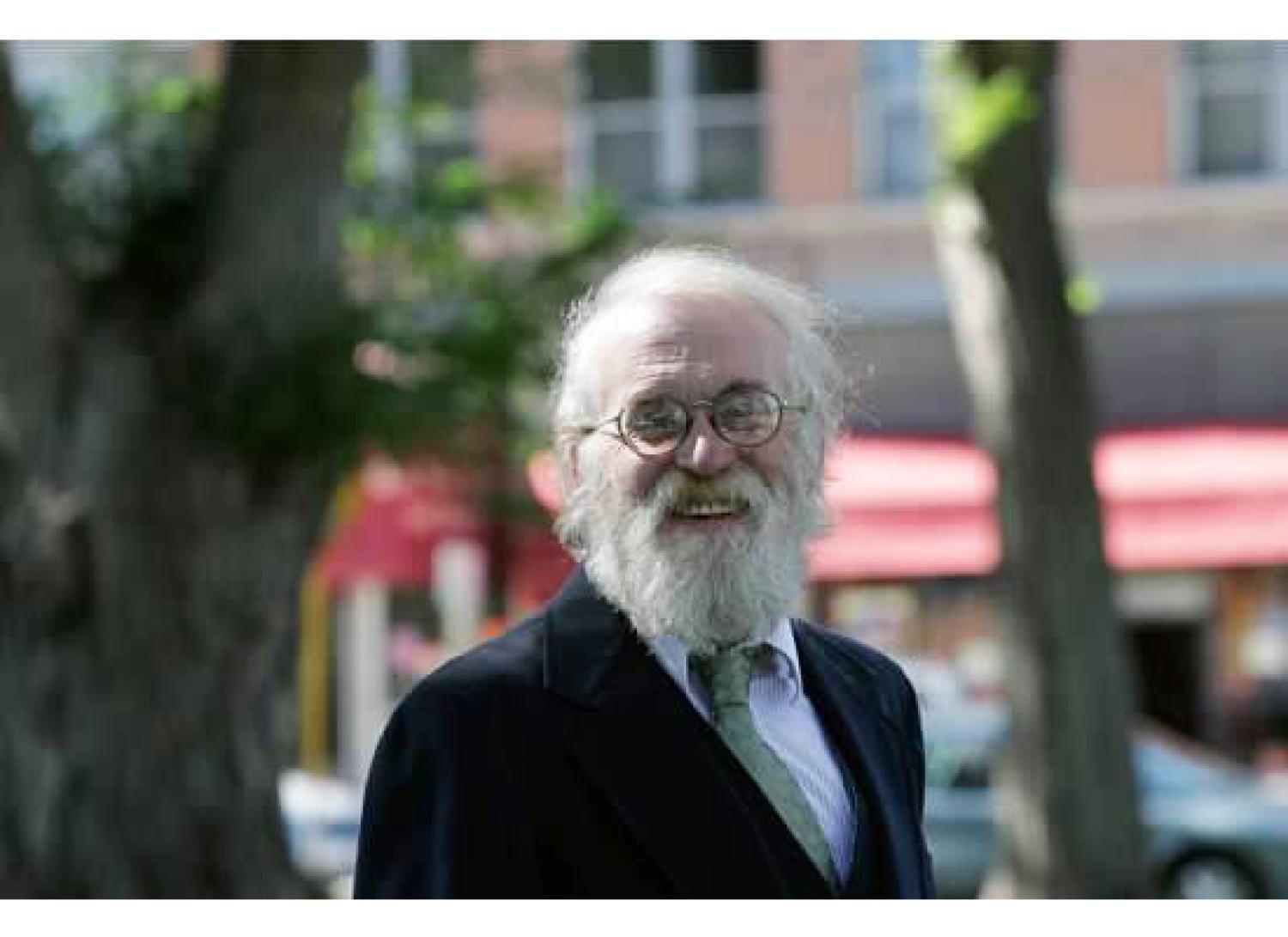

Banner cartoon image by Bob Mankoff. The cartoonist Bob Mankoff was the first visitor in the Center’s Humor Initiative series.