Making the Most of Science:

The Prequel and Sequel, Combined

The Power of Mudwrestling to Interrupt a Rescue

By the terms of a long-running dream, scientists were going to rescue us from our feuds and quarrels. When we lost our footing and sank into the swamp of squabbling, scientists would show us how to pull ourselves out of that bog. Researching the problems that had turned us against each other, scientists would reveal the origins and dynamics of those problems. These experts would shine a bright light on our dilemmas, and our trust in that light would deliver us to firm ground and to solutions. The core of the dream was this: the findings of scientists would provide citizens with an alternative to settling into the swamp of contention. Their findings would rescue us from putting the muck and mire of that swamp to use for prolonged mudwrestling among ourselves. But this dream has had a hard time turning into a reality. Instead, sometimes over their protests and sometimes with their full consent, we have often pulled the scientists into the mudwrestling.

Resurrection as a Literary Genre Whose Time Has Come

The opening paragraph that you just read goes straight to the heart of the worry that preoccupies me in 2020.

I fear that scientific efforts to end—or, at least, to slow down—the pandemic will struggle for success because of the troubled state of the relationship between society and science. Struggling to deal with Covid-19, we have placed an enormous burden of expectation on the microbiologists, epidemiologists, specialists in infectious diseases, and experts in public health who are investing endless hours in their search for vaccines, treatments, and ways to constrain the contagion. But the tensions of 2020 have generated mountains of impatience, skepticism, and distrust that will stand in the way of mobilizing the scientists’ findings to rescue the nation. Thus, the opening paragraph of this “Not My First Rodeo” post summarizes the range of attitudes— from hopeful expectation to disillusioned distrust—that are currently aimed at scientists.

You have every reason to think that I wrote the first draft of that statement in late October of 2020.

I did not.

Nearly all of it is drawn from a report, Making the Most of Science in the American West: An Experiment, co-authored by me and Claudia Puska, a talented young thinker affiliated with the Center of the American West. We wrote this report seventeen years ago.

So what are we to make of that?

Did Claudia and I foresee the arrival of the coronavirus, the multiple afflictions it has brought to our world, and the disputes aroused by the conundrums of testing, treatments, vaccines, and techniques for the prevention of contagion?

We certainly did not.

Made possible by support from the National Park Service (thanks in large part to Randy Jones, former Superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park and also former Deputy Director of the National Park Service), our 2003 report drew on the history of naturalists and scientists in the American West and applied that history to contentious issues in the management of public lands. It was our undisguised hope to lay out the terms of a better relationship between society and science. Many passages in that report give the impression that we wrote them this week.

Steering by the Center of the American West slogan of “turning hindsight into foresight,” I am resurrecting that report with the hope that this will help with our dilemmas in 2020. Written in an entirely different era from today, several features still qualify for another chance at life— the very definition of resurrection.

Resurrecting an old report is not a well-worked-out literary craft, and it has certainly not arrived as a literary art. The greatest danger of such an effort is easy to identify: any slip in the direction of the “I told you so!” stance will instantly reduce its value. A lesser peril lies in the boredom of a cut-and-paste operation of simply moving paragraphs from one format to another. To deal with that lesser peril, I have tampered a little with the original text in the interest of clarity and relevance, and, from time to time, I have added very explicit statements about conditions in 2020. And, to reduce the danger of the inadvertent adoption of a “We told you so!” stance, I will say again that Claudia and I did not predict the crises of 2020. Instead, we identified and called attention to patterns in the history of science in the American West that continue to be in play today, even though their long-running historical pedigree rarely gets recognition.

Here is a wild statement that takes a calculated risk in singling out two currently famous figures in order to explain why Making the Most of Science in the American West deserves resurrection in 2020:

Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Dr. Deborah Birx, Response Coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, would have been better prepared for the challenges they have faced in 2020 if they had read the Center’s 2003 report and become acquainted with the experiences of naturalists and scientists in the nineteenth-century American West.

Here’s why.

First, the history of westward expansion holds an abundance of evidence-based stories that double as cautionary tales, or even as maps to the landmines and pitfalls that scientists in later times would be wise to anticipate. This history discloses patterns in the relationship between science and society that have been in the picture for a long time and do not need to catch us by surprise.

Second, paying attention to history allows hard-pressed people to take an excursion in time—a brief departure from the conflicts and contests of the present—that can clarify the mind and calm the passions.

Third, the settlement of the West and the rise of American science are “sibling” histories. They grew up together, and you cannot understand one without the other.

What do I mean by referring to the history of science and history of westward expansion as “sibling” histories?

In the nineteenth century, the West offered American naturalists and scientists what the historian William Goetzmann called “a vast natural laboratory,” providing spectacular opportunities to build careers and reputations. Indeed, many Western landscapes seemed almost designed and prepared for scientific attention. In the West, aridity left landforms exposed and open for study, and also raised instant questions about the way that organisms had been able to adapt to conditions that seemed very alien to naturalists and scientists familiar with the Eastern United States. In innumerable ways, the professionalization of American science arose from and connected directly to the reconnaissance of the landscapes and resources of the American West.

Trying to conjure up a literary strategy for the resurrection of an old report, this is the best sequence of presentation that I could devise:

Part One: Two passages taken directly from the Making the Most of Science report that drive home two perspectives that I yearn to have widely recognized in 2020 and applied directly to the search for medical solutions for the pandemic.

Part Two: The statement of the central point of the report: American history does not record a golden age when science was separated from the federal government. In other words, American science was politicized from its origins.

Part Three: Three historical stories that offer themselves as parables that we should contemplate—not once, but repeatedly—in 2020.

Part One:

Two Recommendations Carrying Undiminished Relevance from a 2003 Report that Doesn’t Care that it Sailed Past its Expiration Date

When I found these two passages in Making the Most of Science, that moment of rediscovery gave me a sensation that surely everyone has experienced with the change of seasons. You put on a coat that you haven’t worn since last winter, and, in a pocket, you find a $20 bill that has been sitting in the closet since you last wore that coat. These two passages, I believe, are endowed with common sense that is in short supply in our world today. If I am in luck and you agree with me on the value of what you are about to read, please use any means you have to get these statements out into the world where they might do some good.

Extremely Relevant Passage #1: Recognize that there is a significant factor of uncertainty in nearly every scientific conclusion.

The hope that scientists can provide us with firmly settled answers that will last for the ages has been the source of much mischief. Ecosystems and humancommunities are enormously complicated sites of study; they are networks of relationships in which many entities change and transform each other. The direction of scientific discovery in this last century has led steadily toward findings of complexity, which is not the destination that most politicians or advocates prefer. The path of wisdom for Americans is to recognize the solidity and meaning provided by scientific study, while keeping expectations for full and final certainty at an appropriately realistic level. And, in many situations, we must face the fact that if we wait for studies to be completed and certified beyond any imaginable question or challenge, the moment for useful decision-making will be long gone.

Extremely Relevant Passage #2: Face the fact: human beings have many talents, and predicting the future is not one of them.

Forecasting the future is not an easy matter for mortals, no matter how accomplished those mortals may be in the experimental method or how firmly they base their predictions on solid data sets drawn from the past and the present. Asking scientists to predict what will happen, if we take one course of action or another, may be the toughest assignment we give anyone in society. There is much to recommend in the adoption of the “least regrets” strategy, by which we make our peace with the unknowability of the future and try to choose the actions that will be least likely to deliver us to outcomes we will regret.

Part Two:

American Science and the American West: Twins Politicized at Birth

An unmistakable characteristic of nineteenth-century scientific practice was its association with the federal government and its dependence on federal funding. Lewis and Clark, to take an early example, did not initiate or bankroll their own expedition. In our own times, it is not uncommon to hear people lament the fact that science has recently become politicized. A historical perspective reminds us that science became politicized several centuries ago, if we give “politicized” the definition associated with the purposes and goals of the nation and caught up in internal and external struggles to shape those purposes and goals. Indeed, from a historical perspective, one could argue that science today is notably less “politicized” than it was in past centuries. Imperial powers sponsored the expeditions of early European scientists, and the United States adopted that practice soon after the nation’s founding. Throughout the nineteenth century, scientists pursuing opportunity had to jockey for support and validation in the arena of politics, currying favor with Congress, the Army, the Secretary of the Interior, the voters, and sometimes, the President. To regret a loss of innocence in the practice of science today requires the “regretters” to shut their eyes to history. The historical record cuts short any temptation to imagine a past period of innocence, when scientists followed the mandates of pure curiosity and did their work in an arena sequestered from the interests and pressures of the nation’s elected and appointed officials.

Given the fact that the federal government played a central role in the origins and professionalization of American science, it doesn’t make an ounce of sense for anyone in 2020 to be shocked to find that “science has become politicized.” On the contrary, there is every good reason to draw on this long history to devise “Best Management Strategies” for refusing to be surprised by the current state of science’s politicization, and to get to work on assessing and managing the current manifestation of this centuries-old dilemma.

Part Three:

Three Historical Stories that Volunteer as Parables

Parable #1: Why Meriwether Lewis, if Given the Powers of Time Travel, Would Say to the Scientists Who Are Researching Covid-19 Vaccines, “So You Think YouHave a Tough Job”

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson gave Meriwether Lewis instructions for his expedition to the Pacific. Jefferson told Lewis to pay attention to everything under the sun, including the sun. Even a partial list of the items that Jefferson asked Lewis to observe and report on conveys a sense of the breadth and ambition of the nineteenth-century agenda for naturalists in the field.

- The courses of rivers and streams

- Astronomical observations to ascertain latitude and longitude (“to be taken with great pains and accuracy”)

- For each Indian tribe, the territories, intertribal relations, language, traditions, monuments, agriculture, fishing, hunting, war, arts, food, clothing, domestic accommodation, diseases, remedies, “peculiarities in their laws, customs, and dispositions,” and articles of commerce

- The “soil and face of the country, its growth and vegetable productions”

- The “animals of the country,” including the remains of those that might be extinct; “the mineral productions of every kind”

On top of all these terrestrial observations, Lewis was instructed to report on the climate, “as characterized by the thermometer, by the proportion of rainy, cloudy, and clear days; by lightning, hail, snow, ice; by the access and recess of frost; the winds prevailing at different seasons; the dates at which particular plants put forward, or lose their flower and leaf; times of appearance of particular birds, reptiles, or insects.”

Contemplate Meriwether Lewis’s assignment, and the society’s 2020 charge to scientists –“Find a safe and effective vaccine and find it fast!”—looks more like business as usual. It wouldn’t be the worst idea to include Jefferson’s instructions to Lewis in every training program in science, with the explicit statement: “Want to be a scientist? Anticipate the possibility of an absolutely impossible demand from society!”

Parable #2: How John Wesley Powell Stepped Forward to Remind Us that Scientists Are Also Citizens, and They Are Sometimes Citizens Who Feel an Obligation to Put their Expertise to Work to Warn their Nation of an Impending Peril

As a founding father of scientific practice in the American West, John Wesley Powell was a high achiever. In 1869 and 1871, John Wesley Powell led the first descents of the Colorado River. In the 1870s, he headed one of the major federal surveys of the West. In 1879, he published the influential study, ˆ. He became the second director of the United States Geological Survey and the founding director of the Bureau of Ethnology. Powell, his biographer Donald Worster declares, had become “the government’s leading scientist.”

While John Wesley Powell unmistakably enjoyed outdoor adventure, he was also a thorough utilitarian, not exactly “St. Powell of the Environmentalists,” as he has sometimes been por- trayed. Still, he certainly had a fine moment when he spoke to the Irrigation Congress in Los Angeles in 1893. The Irrigation Congress members thought of Powell as their founding father; they assumed they would hear his enthusiastic support for the cause of irrigating the West. But Powell caught them by surprise. “When all the rivers are used,” he said to the increasingly crestfallen Congress members, “when all the creeks in the ravines, when all the brooks, when all the springs are used, when all the reservoirs along the streams are used, when all the canyon waters are taken up, when all the artesian waters are taken up, when all the wells are sunk or dug that can be dug in this arid region, there is still not enough water to irrigate all this arid region.” “What matters it whether I am popular or unpopular?” he declared. “I tell you, gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply these lands.”

Contemplating this moment makes one wonder if it would be in our interests to license scientists to speak very directly, even sharply to us, if they think we are getting ourselves into a pickle. But it is common for policy specialists to caution scientists against confusing their personal values with their science. That is generally excellent advice, but it is also advice that discourages the reoccurrence of occasions like Powell’s warning to the Irrigation Congress. In 1893, Powell set a remarkable example of a scientist declaring his indifference to popularity and speaking truthfully and uncomfortably. Should we encourage today’s scientists to do more of that? Or would we only be setting ourselves up for irritation, and the scientists for trouble?

Back in 2003, Claudia Puska and I proposed a pretty good plan for recognizing that scientists are citizens with an uncompromised right to care about the well-being of the world they live in. We proposed a two-stage ritual of communication. In Stage One, scientists present the results of their research. In Stage Two, they shift gears and tell us the meanings that they themselves find in those results, as well as the actions that they would like to see adopted in response to their findings. A scientist could signal this shift with the statement, “I shall now exercise my constitutional right to speak as a citizen.” They could also do this with a flourish or two: shutting off the PowerPoint, taking off the psychological equivalent of an authority-laden lab coat, and standing before the audience as an appealing human being, momentarily without “tech support.” With this distinction—between the Scientist and the Citizen—made clear and unmistakable, it would be harder for partisans to dismiss the results in Stage One as the doubtful product of the preferences communicated in Stage Two.

In 2020, it seems unlikely that any scientists, working in biomedicine or climate science, begins every morning with the ritual of reciting Major Powell’s words: “What matters it whether I am popular or unpopular?” And yet, in a nation still attempting to conduct itself as a democratic republic, scientists might want to try an experiment, starting each day with a variation on Major Powell’s words: “It may or may not matter whether I am popular or unpopular, but it matters a lot whether I am trusted or dismissed.”

Parable #3: John C. Frémont Offers A Cautionary Tale in Telling One’s Bosses What They Want to Hear

John C. Frémont was far more an explorer scouting out the promise of the West for national expansion than he was a naturalist or scientist-in-the-making. But he devoted much of his attention to recording his observations of the natural settings he encountered, and the landforms, plants, and animals he saw. Only a narrow and persnickety definition of “scientist” would remove him from the history of science in the West. In that framework, Frémont’s report on the outcome of his fourth expedition offers a cautionary tale for the ages.

In 1848, Frémont’s fourth expedition was a solid disaster. He attempted to find a railroad route through the southern Rockies, venturing into very difficult terrain in winter. Out of the thirty-three originally in the party, eleven men died, and survivors accused one another of cannibalism and desertion. Frémont’s reporting of the outcome took some liberties with the reality: “The result,” Frémont said, “was entirely satisfactory. It convinced me that neither the snow of winter nor the mountain ranges were obstacles in the way of the [rail]road.” The desire to give a favorable report to one’s sponsors, as this example indicates, played a significant role in the written records of exploration, though few have equaled Frémont in this zone of achievement.

We are in his debt for this high-powered, industrial-strength cautionary tale.

A Heavy-Handed Concluding Remark

Whatever happens in the Presidential Election in November of 2020, the relationship between science and society in 2020 will require careful stewardship, resting on a foundation in historical perspective.

If there was no golden age for science in the past, and the history of science in the nineteenth century West offers us an abundant supply of inspirational tales and cautionary tales, then there are no grounds for naïveté today.

Anyone Inclined to Join the Team?

I eagerly invite audience participation, encouraging any readers so inclined to try their hand at tracking the similarities and difference between the challenges facing biomedical scientists today, and the challenges facing environmental scientists nearly twenty years ago. You can find the original report in its entirety at our website.

If you find this blog contains ideas worth sharing with friends, please forward this link to them. If you are reading this for the first time, join our EMAIL LIST to receive the Not my First Rodeo blog every Friday.

Banner Image Caption – 2020: The Right Time for Dr. Fauci and Dr. Birx to Get Better Acquainted with Captain Lewis and Major Powell.

Photo Credit:

Captain Meriwether Lewis image courtesy of: Wikipedia

Major John Wesley Powell image courtesy of: Wikipedia

Dr. Anthony Fauci image courtesy of: Wikipedia

Dr. Birx image courtesy of: Wikipedia

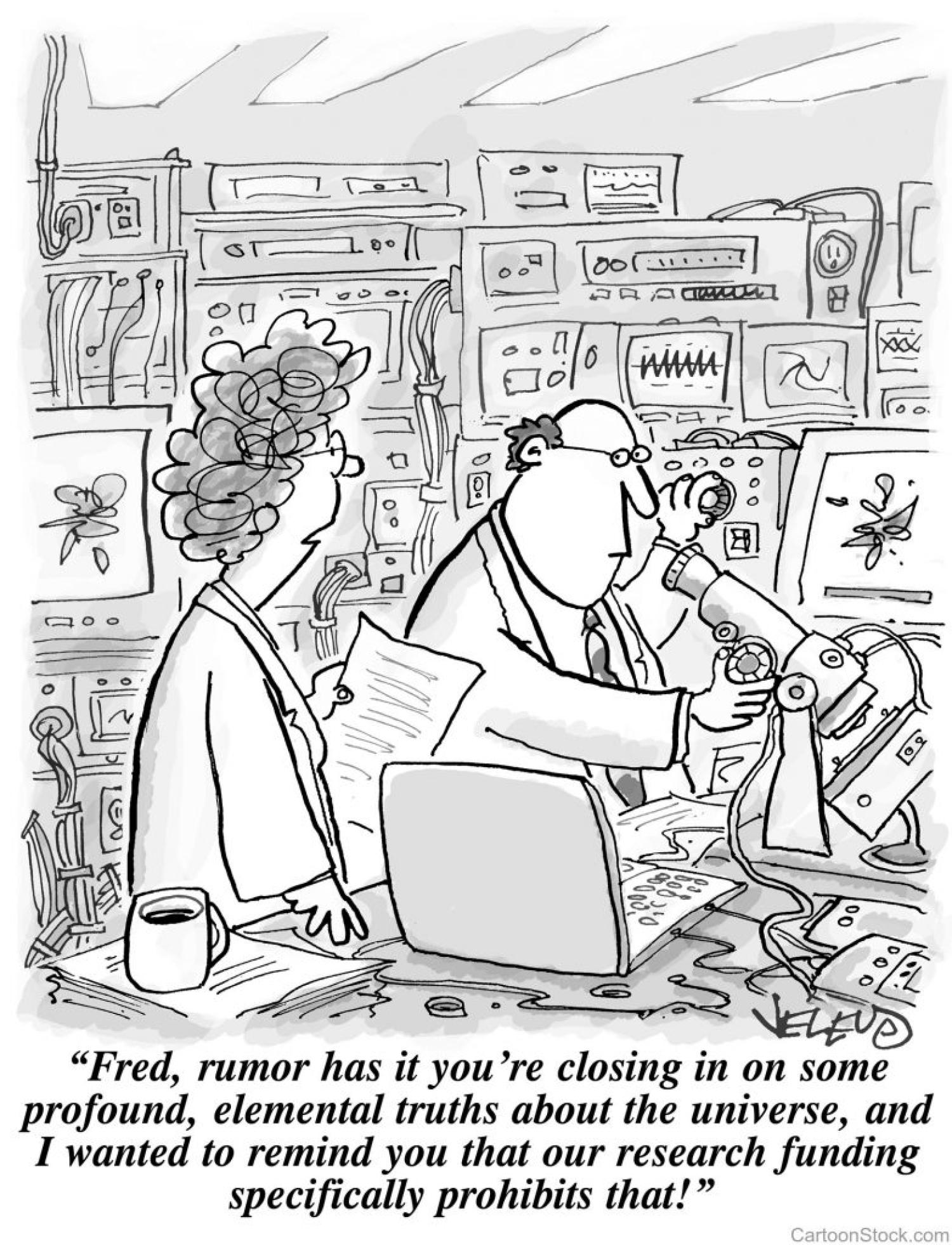

Cartoon image courtesy of: https://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=bven532