History of Early Cyprus

Introduction

Introduction

The island of Cyprus is located in the northeast corner of the Mediterranean Sea, south of Turkey, west of Lebanon and Syria, north of Egypt, and southeast of Greece. Its location made the island a crucial link in trade relationships between Greece and the Near East, the Levant, and Egypt and, as a result, Cyprus was always subject to myriad foreign influences.

The modern word "copper" is derived from the island's name, a nod to the island's rich copper resources, which also contributed to its broad significance in the ancient Mediterranean world.

The chronology of ancient Cyprus in some ways matches the established chronologies for other Mediterranean cultures, but the development of the island followed its own trajectory. Absolute dates are hard to pinpoint, but scholars generally agree on the broad outline of developmental stages of the island's art, technologies, and culture.

Neolithic Period (Stone Age): 7,000-4,000 B.C.E.

The earliest visitors to Cyprus around 10,000 B.C.E. were seasonal hunters of pygmy elephants and pygmy hippopotami. A significant early settlement site on the island, called Choirokoitia, dates to as early as 7,000 B.C.E. and was occupied until around 4,000 B.C.E. Residents here lived in circular houses of mudbrick and stone with flat roofs and used vessels made of stone. This phase is divided into two sub-phases: the Aceramic Neolithic and the Ceramic Neolithic, based on the production and use of ceramic vessels. In the latter phase, which started around 5,500 B.C.E., residents of the island began using Combed Ware pottery, which had arrived with an influx of new settlers (1).

Chalcolithic Period (Copper Age): 4,000-2,600 B.C.E.

A major earthquake around 3,800 B.C.E. heralded the end of the Neolithic and marked the beginning of the Chalcolithic Period. The number of settlements on Cyprus increased during the Chalcolithic period and although we can identify cultural changes, it is clear that this was a continuation of cultural development from the Neolithic period. Chalcolithic Cypriots continued using stone, but also began using copper for objects like chisels, hooks, and jewelry (2). This combination of materials contributes to the name of the period, which is a combination of the words "chalkos," meaning copper, and "lithos," meaning stone.

Red-on-white pottery predominates during the Chalcolithic period. Also common are clay and stone female figurines, such as a limestone figurine of a fertility goddess at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The accentuated genitals on these figurines contribute to their association with fertility rites. Some figurines, however, are more abstract, including three cruciform figurines in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. These other cruciform figurines may have developed from the stump-like figurines of the preceding Neolithic period. Given their usual findspot in burials of women and children, cruciform figurines may be associated with fertility, like the female figurines.

Early Bronze Age: 2,600-2,000 B.C.E.

The transition into the Early Bronze Age is hard to pinpoint exactly, as most of the evidence for Early Bronze Age culture on Cyprus comes from tomb excavations and not the examination of actual settlements (3). Some pottery from this period, such as Red Polished Ware, shows a strong resemblance to Anatolian pottery (4) and may have been introduced by newcomers to the island. Several objects found on Cyprus, such as daggers from Minoan Crete and beads from Egypt, also indicate the existence of trade contacts with both these civilizations. At this time, the main export of Cyprus was probably copper, which would likewise be the basis for later development of trade (5). Figurines, especially female figurines, continue to be popular on the island.

Middle Bronze Age: 2,000-1,600 B.C.E.

This was a short transitional period between the Early and Late Bronze Age. Increasing trade relations with Egypt, Syria, and Palestine resulted in the growing importance of the harbor towns on the southern coast. Cypriot pottery began to be traded as well, although the main export continued to be copper (6). The construction of a number of fortresses on the island suggests a period of unrest, although its cause is not known.

Late Bronze Age: 1,600-1,050 B.C.E.

At this time, a new period of peace in the eastern Mediterranean allowed for an unprecedented growth in trade. Cyprus's location in the Mediterranean and its abundant copper resources attracted Mycenaean Greek merchants who established themselves on the eastern and southern coasts of the island in order to conduct trade with the Near East. This increase in trade led to the development of the Cypro-Minoan script (7). Increased trade also stimulated the development of new pottery styles stemming from earlier Bronze Age traditions. These include White Slip and Base Ring Wares, both of which were very popular as exports. Base Ring Ware was especially popular in Egypt, where numerous jars called bilbils, which resemble inverted poppy heads and are thought to have been used to store and transport opium, were exported (8). Mycenaean Greek pottery, both imported and locally made (9), also appears in great numbers on Cyprus, fulfilling the demand of the Cypriot market for the exuberant styles of Mycenaean pottery, especially the Pictorial Style, a famous example of which is the Mycenaean Warrior Vase (10).

Around 1,200 B.C.E., as Mycenaean civilization on the Greek mainland was collapsing, several major cities on Cyprus were destroyed. These destructions have been attributed to Mycenaean refugees who fled their collapsed societies, as well as others who may have joined them in their travels. These invasions are sometimes associated with the mysterious Sea Peoples, a group of raiders known mainly from Egyptian texts but whose identity remains uncertain (11). Following this destruction, a wave of Achaean immigrants settled on Cyprus, bringing with them the culture of mainland Greece and advanced metallurgical techniques. There is also evidence for immigrants from Crete and Persia (12). Many new cities appear at this time, which, according to legend, were founded by Greek heroes from the Trojan War (13). Around 1,050 B.C.E. the Late Bronze Age was brought to a close by a disaster, possibly major earthquakes, which destroyed many of the island's cities (14).

Cypro-Geometric Period: 1,050-750 B.C.E.

Following destruction on the island at the end of the Late Bronze Age, Cypriot residents moved away from the interior of the island towards the coasts and founded several new cities. Immigrants to Cyprus, especially Greeks and Phoenicians, were attracted by the island's rich copper resources, as well as its by its supply of timber. The influence of mainland Greece at this time can be observed in contemporary artifacts, yet a distinct separation was evident between the culture of the Greek settlers and native Cypriot traditions. Toward the close of the Cypro-Geometric period, these two cultures were blended together. Around 850 B.C.E., there was extensive contact with the Phoenicians, who established several colonies on the island (15).

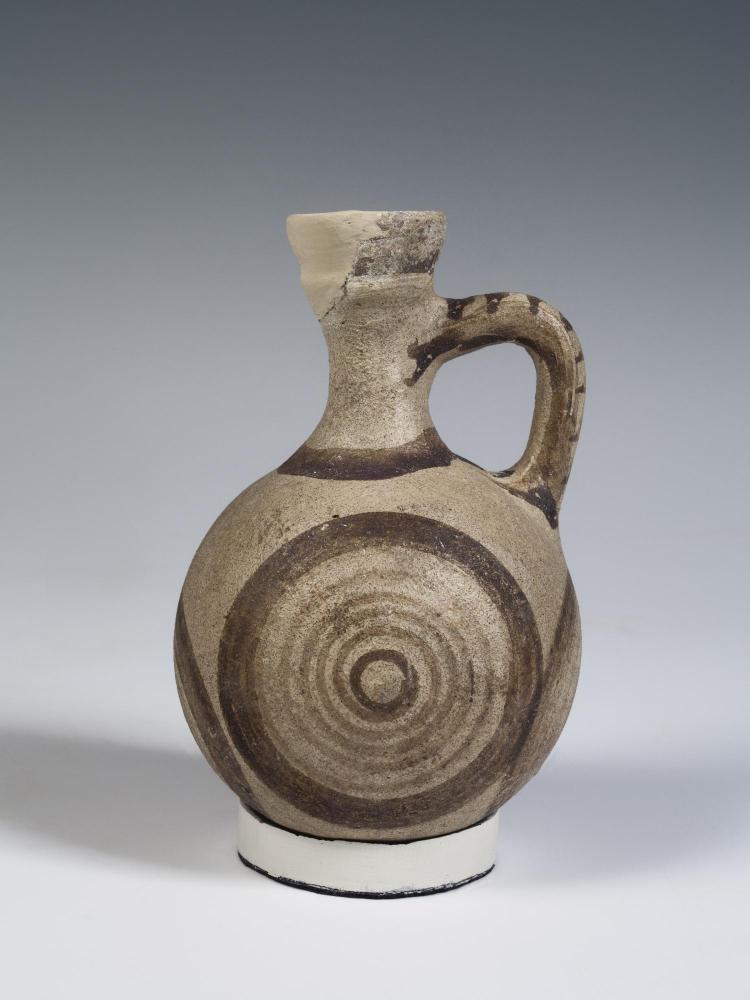

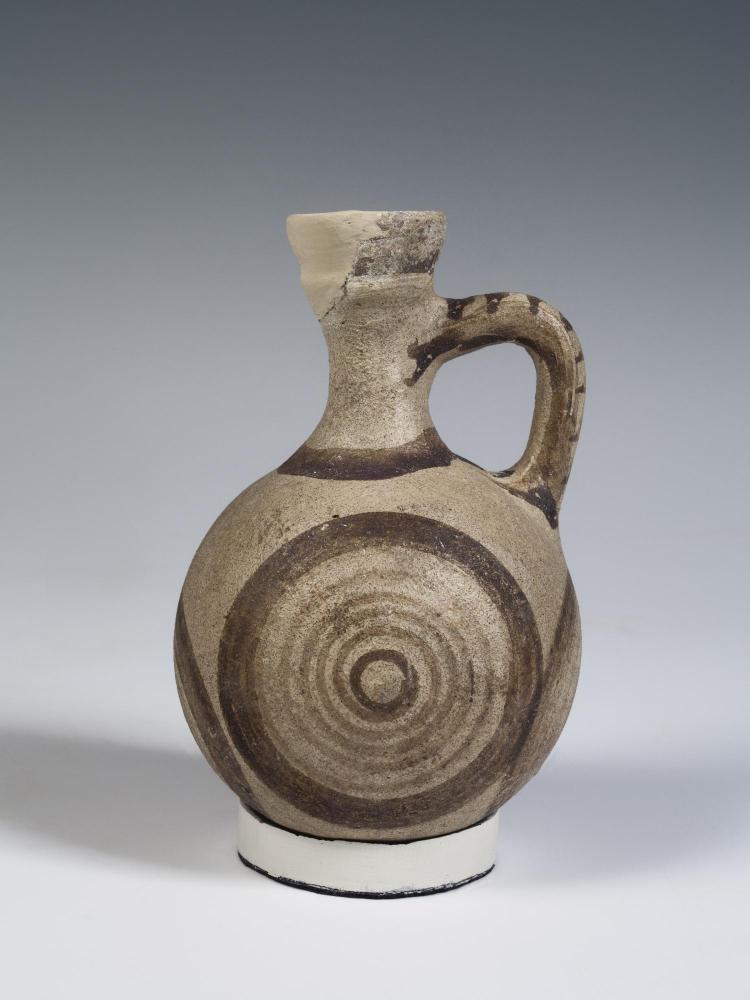

Pottery at this time included white-painted wares, bichrome wares, and black slip wares. A bichrome cup in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is representative of this period. Red slip wares appear later in the Cypro-Geometric period, and pictorial styles continue from the preceding Late Bronze Age. The influx of immigrants, as well as increased trade contacts resulted in blended styles, and an Early Iron Age juglet from Cyprus demonstrates some of the blend of local and foreign influences in Cypro-Geometric art.

Cypro-Archaic Period: 750-500 B.C.E.

By the Cypro-Archaic period Cyprus was divided into a series of city-kingdoms. Around 700 B.C.E., the kings of Cyprus came under the rule of the Assyrian king Sargon II. Cyprus remained under Assyrian domination until after the collapse of the Assyrian Empire around 669 B.C.E.. Assyrian rule was lenient as long as tribute was paid and Cypriot rulers grew rich and pleasured in exotic goods, as the royal tombs at Salamis on the east coast of the island indicate. Under the Assyrians, contact between Cyprus and the Aegean world increased (16).

After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, Egypt grew in power and by 570 B.C.E. Cyprus was essentially ruled by the Egyptians. Though Egyptian control only lasted for 25 years, Egyptian art styles, along with Ionian styles, had a marked influence on Cypriot sculpture, as well as Archaic sculpture in general (17). In 545 B.C.E., Cyprus came under the control of the Persian Empire.

Pottery in the Cypro-Archaic period is similar to that of the preceding period and included white-painted wares, bichrome wares, and black and red slip wares. A whimsical example of Cypro-Archaic pottery is a trick vase in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This vase is shaped like a bull and unlike typical vases, it is filled through a hole in the foot and its contents poured through a hole in the bull's mouth. Trick vases first appear in Cypriot art in the Cypro-Geometric period. This

Classical and Later Cyprus: 500 B.C.E. and Beyond

After 499 B.C.E., Persian rule became much harsher (18) and Cyprus remained in Persian control despite attempts at liberation by the Greek city-states (19). Throughout the Classical period (5th and 4th centuries B.C.E.) Cyprus remained under Persian control. Cyprus finally regained relative freedom for a short time when the Macedonian king Alexander the Great granted greater independence to the island. Following his death in 323 B.C.E., Cyprus was annexed by Egypt, under whose control it remained throughout the Hellenistic period (20). In 58 B.C.E. Cyprus became a Roman province (21).

This essay was written to accompany a collection of Greek artifacts at the CU Art Museum.

Collections of Cypriot Antiquities Online:

- The Cesnola Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

- The Belcher Collection at the Institute of Cypriot Studies at SUNY Albany in New York

Footnotes

- Vassos Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1982): 16-27.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 30-37.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 40.

- Vassos Karageorghis, The Ancient Civilization of Cyprus (New York: Cowles Education Corporation,1969): 38-39.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 46.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 52-60.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 61-66.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 73-76.

- A. D. Lacy, Greek Pottery in the Bronze Age (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1967): 167-168.

- Emily Vermeule, Mycenaean Pictorial Vase Painting (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982): 6-9.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 82-86.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 89-106.

- Andreas Demetriou, Cypro-Aegean Relations in the Early Iron Age (Cyprus: Zavallis Litho Ltd., 1989): 88-93.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 112.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 114-127.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans:128-136.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 138-139.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 152.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 157.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans:167.

- Karageorghis, Cyprus from the Stone Age to the Romans: 177.