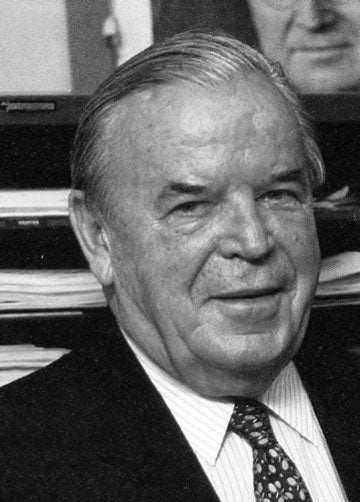

Edward Rozek

Near the end of World War II, a young Polish soldier, temporarily blinded by an anti-tank mine, began his new life in the dark.

By 1945, Edward Rozek had fled his homeland and spent time in a Nazi slave labor camp. He had fought his former captors in France and Germany, earning numerous medals. Then, as he spent nearly a year recovering from surgery on his eyes, he made a decision.

“Because he couldn’t see, he had plenty of time to think,” says Rozek’s wife, Elizabeth Rozek. “He began thinking, ‘Why is it that every generation or so the old men of one country send their young men to fight against the young men of another country?’ He decided that there had to be a better solution, and that started with teaching young people.”

Rozek died Feb. 19 in Boulder. He was 90.

When Rozek arrived in the United States, he carried $50 and a drive to find the best education in the country, his wife said. He worked on a dairy farm and in an auto shop to save enough money for tuition to Harvard, where he soon earned scholarships that carried him through advanced degrees.

For the next several decades, Rozek concentrated on studying his way into the top tiers of academia, earning a place as an international relations expert and vehement anti-communist. On campus, in the classroom and even in retirement, he consistently set sparks of debate and reveled each time they caught fire.

Rozek joined the CU political science in 1956. Soon afterward, one of his students was an accounting major named Hank Brown (Acct’61, Law’69).

“I remember in the first class I had from him I missed the third lecture,” says Brown, who served as CU president from 2005-2008. “And in a class of more than 250 he noticed I’d missed one lecture and he announced to the class that whoever knew me should tell me that I was to come to his office immediately…he made it clear to me that it was inexcusable that I miss a single class.”

During his 43 years at CU, Rozek chaired the Institute for the Study of Comparative Politics and Ideologies and directed the Central East European Studies Program, among others. He was known to spend days preparing for a single lecture, and quickly earned a reputation for classes as riveting as they were demanding.

“He took great delight in engaging with people who would debate with him – especially those who disagreed with him,” said Brown, who now teaches in the same department where Rozek taught. “People who did that would often get the best grades in the class.”

Throughout the years, Rozek never wavered in his staunch warnings about what he saw as the constantly lingering threat of communism and in 1980 was tapped as an advisor to Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign.

Following his retirement in 1999, Rozek focused his ire at university bureaucracy and what he saw as a lack of intellectual diversity, barraging local newspapers with editorials. He even trained his poison pen on a former student.

“Administrators were not his favorite group of people,” Brown says, in a not-so-subtle understatement. “I suspect that I was a bit of a disappointment to him in that regard.”

In 2008, Rozek bought a full-page advertisement in the Boulder Camera alleging a disparity between registered Democratic and Republican professors, claiming the university suffered from “ideological incest.”

“Ed’s view was that the purpose of an education is to get people to think, and if they don’t think they just accept,” says Elizabeth Rozek, to whom he dictated most of his op-ed articles. “He maintained that the purpose of education is not just ingestion of information. It’s learning to think for yourself.”

Despite his intimidating reputation, Rozek’s wife says he also remained guided by a compassion ingrained as he recovered from the injury that nearly blinded him in the war that shaped so much of his life. On his first visit back to Poland after the fall of communism, he spent hours at a Polish orphanage for blind and deaf children. After his death, his family directed all donations to the orphanage in his name.

“He was always mindful,” his wife says, “that there but for the grace of God, he could have gone.”