It’s been 25 years since sociology professor Michael Radelet decided to publicly denounce the death penalty, but he can still recall the children’s cries that made him do it.

It’s been 25 years since sociology professor Michael Radelet decided to publicly denounce the death penalty, but he can still recall the children’s cries that made him do it.

It was 1 a.m. on July 13, 1984, six hours before David Washington, a convicted triple-murderer, was to be sent to the electric chair. Radelet, then a young sociology professor with an interest in capital punishment, had gotten to know Washington well through his research. When execution day came, he looked on as the man’s wife and young children said their tearful goodbyes. Then he walked them out of Florida State Prison’s death row.

“His daughters just kept screaming as we left, ‘Please don’t kill my daddy,’ ” Radelet recalls. “I thought, ‘What good is it going to do to kill this guy and leave another family behind to mourn the loss of a loved one?’ ”

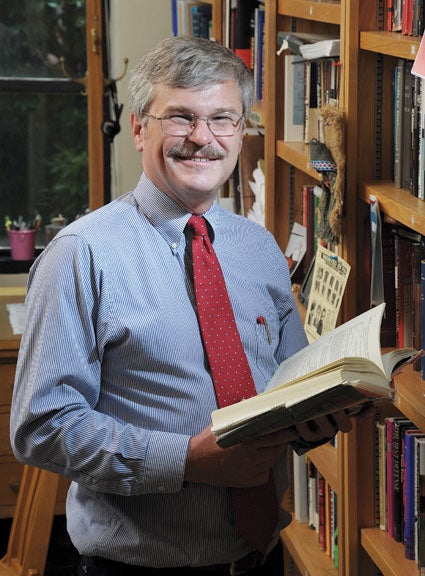

A quarter-century later, such unconditional sympathy for victims of tragedy remains a driving — albeit controversial — force in Radelet’s career, leading the 58-year-old to advocate as fiercely for death row inmates and their families as he does for the parents of homicide victims. Since publishing his first paper in the ’80s, he has written dozens on wrongful conviction, racial bias and other issues surrounding capital punishment. He also has conducted pivotal research that has led legislative bodies to reconsider the death penalty, testified at 75 trials and developed relationships with more than 100 death row inmates, including infamous serial killer Ted Bundy.

Radelet also has forged a less-publicized, seemingly unlikely alliance with those who occupy the other side of the courtroom aisle — families of murder victims. Since his arrival at CU-Boulder in 2001, he and his students have gathered reams of data on unsolved homicides in Colorado and worked alongside family members to craft a first-in-the-nation bill that would ban the state’s death penalty and put the money saved toward investigating cold cases.

In March, it failed in the Colorado senate by one vote after passing in the house.

“I have found that families of homicide victims and families of death row inmates have a lot more in common than they have differences,” says Radelet, seated in a cluttered office decorated with personal notes from Bundy and recognition plaques from the Families of Homicide Victims and Missing Persons. “They have all taught me an incredible amount over the years, and I can pass that knowledge on to my students,” he says.

The bottom of the ladder

Radelet’s gravitation toward society’s underdogs began in his teens when, as a student at a Catholic high school in Lansing, Mich., he traveled to Chicago to do charity work with elderly poor. After earning his doctorate in sociology from Purdue, he landed a teaching job at the University of Florida in 1979, and before long his curiosity brought him to a Students against the Death Penalty meeting.

“I always had an interest in working with people at the bottom of the ladder,” he says.

Sociology professor Michael Radelet conducted a 2003 study with 50 undergraduate students finding, among other things, nearly one-third of those executed in Colorado have been minorities.

Initially, he had no firm opinion about capital punishment. But the more he learned, the more it troubled him.

In 1981, he published a seminal study of 600 Florida homicide cases, concluding that those accused of murdering whites are far more likely to be sentenced to death than those accused of murdering blacks. Since then, his research, along with that of others, suggests ethnic minorities are more likely to be sentenced to death than whites, and that wrongful convictions are higher than previously believed.

Since the 1859 hanging of John Stoefel from a cottonwood tree in Denver in what was then the Kansas Territory, another 102 legally mandated executions have been carried out in Colorado through April 2009, Radelet says. Ninety percent of those were put to death for killing white people, according to a 2003 study conducted by the professor and his students. Nearly one-third of those executed have been minorities, a “disproportionate” number given the state’s small minority population for most of its history.

To date, 238 felony inmates have been exonerated nationwide due to DNA evidence, according to the Innocence Project (17 had been sentenced to death). In all, 133 inmates have been released from death row with either a pardon, charges dismissed or an acquittal. And studies in Florida and Illinois suggest death penalty cases are often riddled with errors.

“The question people have been asking for 30 years is ‘Who deserves to die?’ The more important question is ‘Who deserves to kill?’ ” Radelet says. “We make so many mistakes that the only clear lesson is that we do not deserve to kill.”

Criminals and their families

Much of his research is based on studying and developing working relationships with hundreds of death row inmates and their families. His goals are to learn what their family backgrounds are, details of the criminals’ lives, what living in prison is like and how they view the problem of criminal violence.

For a decade, he and Bundy met regularly in a Florida prison, where Bundy scrawled drawings of his cramped cell and shared hundreds of letters he had gotten from what Radelet calls “death row groupies.”

He offered Radelet a unique insight into the disturbed mind of a serial killer; in return, Radelet offered a connection to the outside world.

“We got along quite well as long as he was in handcuffs,” he quips.

Make no mistake, he stresses. “You don’t oppose the death penalty because these guys are great citizens. You oppose it because of what it does to us as a society.”

Others disagree.

Radelet met a barrage of criticism and death threats after publishing a 1985 study reporting that since 1900, 23 innocent people had been executed. Since then, detractors have accused him of being insensitive to victim’s families.

Others like retired Adams County, Colo., prosecutor Bob Grant, who has prosecuted more than a dozen death penalty cases, feels the death penalty should remain intact. He frequently visits Radelet’s classes to offer his perspective.

“There has never been an execution in this country where the individual was later exonerated,” asserts Grant, noting that “not convicted” and “innocent” mean very different things. He feels many people have been released from death row either for political reasons, lack of evidence or prosecution errors — not because someone proved they did not commit the crime.

Investigating homicides

Howard Morton, whose son was murdered in 1975 at age 18, had just founded Families of Homicide Victims and Missing Persons when he first heard Radelet speak in 2001. For him, he says, the death penalty was a nonissue at the time.

“I told him, ‘You can’t be for or against the death penalty if you haven’t found the murderer yet.’ You’re talking to the wind.”

In response, Radelet invited Morton to speak to his criminology class, and soon 12 of his students embarked on a project to investigate unsolved homicides. Thanks in part to those student efforts and those of subsequent classes, The Families of Homicide Victims and Missing Persons group has grown from 11 members to 600 and collected data on 1,445 unsolved Colorado murders. Kelly Fernandez-Kroyer (Soc’04) — one of the original 12 students — took a job with the organization.

A growing body of research shows that a death penalty sentence — complete with its multiple appeals, lengthy trials and fees for expert witnesses — costs taxpayers more than a life sentence without parole.

For instance, a 2008 California study found that the state pays $90,000 per year more to confine an inmate to death row than to a maximum security prison, costing the state an extra $63.3 million annually. Such numbers swayed Morton.

“In the last 40 years there have been 7,000 murders in Colorado, and we have executed one guy and it has cost us millions of dollars a year,” he says. “It is a failed government policy.”

Such comments make Radelet proud.

“When I teach, I really challenge students to become involved in the important issues of our day. I tell them,

‘I don’t care what side you are on. I don’t care if you agree with me. The trick is to pick an issue to get involved in, make a stand and stick with it for the long haul.

I teach commitment.”