Blanketflower is native to western North America. In Colorado, it is most common from the grassland-forest ecotone at the edge of the foothills to the upper limits of the ponderosa pine at elevations of approximately 9,000 feet. It is part of a fascinating relationship with a night-flying moth, the Schinia flowermoth (Schinia masoni). Insects and flowering plants have been competing and cooperating for ages – these ecological relationships have played an important evolutionary role in shaping species. The Schinia flowermoth is completely dependent on the blanketflower as its only host plant. The flowermoth lays it eggs solely on blanketflower, allowing its larvae to feed on the plant’s seeds. To avoid being eaten, the adult moth has evolved coloring very similar to the blossoms of the plant. This relationship is the result of a long process of coevelolution.

Connection to Fire

Blanketflower increases dramatically in areas where there has been fire, usually flowering withing one year after an area has burned. The Schinia moth follows the Blanketflower into these areas. Over time both populations decrease and become uncommon in places that have not burned for decades. The presence of these specis help researchers understand how fire influences the ecology of a region.

Here is a lovely description of one observer’s experience with blanketflower:

“I saw my first flowermoth in early June 1987, near Boulder, Colorado. The half‐inch‐long moth was dallying on a blossom of blanketflower (Gaillardia aristata); the flower's burgundy and yellow colors reminded me of a split, ripe peach. The wine‐colored wings and yellow head and thorax of the moth were a perfect match. I was amazed and delighted, and I began to look into what was known about this species.”1

Connection to Collections

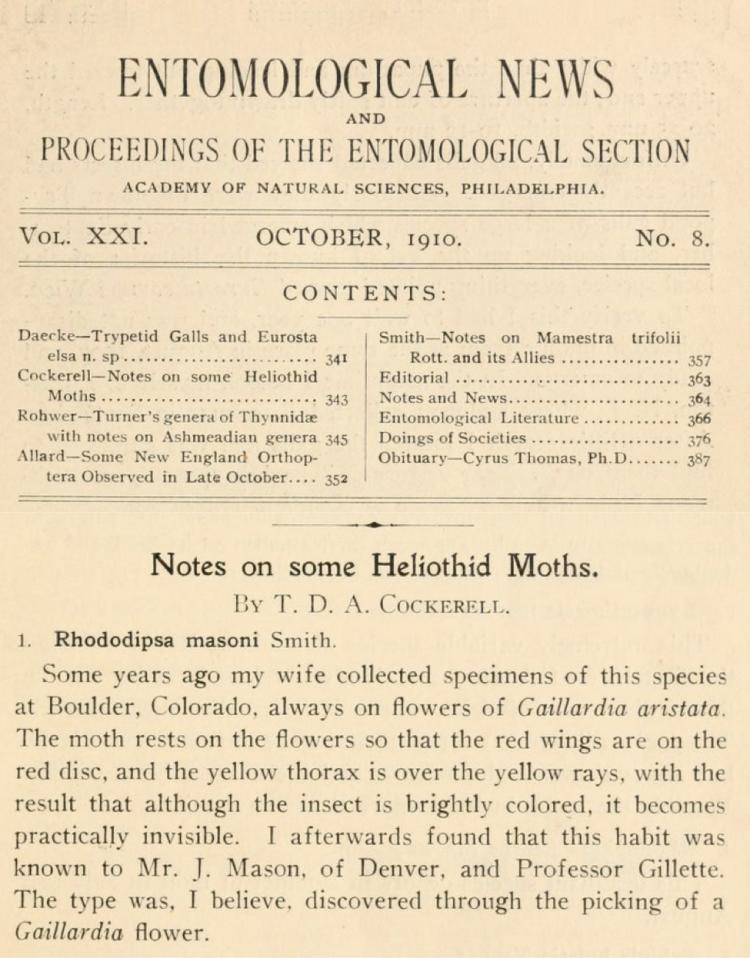

The moth Schinia masonii was named for Mr J Mason who had collected butterflies and moths in Denver. He knew of the link between this moth and host plant species. T.D.A. Cockerell speculated that Mason had found this link while picking a Gaillardia flower on which a moth happened to be resting2.

The CU Museum’s Entomology collection holds a Schinia masonii specimen collected by Cockerell on flowers of Gaillardia aristata. It is possible that this is the specimen reported on by Cockerell3. Cockerell was important in the early development of the CU Museum.

So, we started with a plant dug up while abloom in a Colorado canyon and ended with a unique moth in a museum collection 110 years after its collection. Thus is the way of these wonders.

Taxonomy: Gaillardia aristata

See All Wonders of the Week!

1. Bruce Byers, 2017. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment: 51-52.

2. Cockerell, 1927. Zoology of Colorado.

3. Cockerell, 1910. Entomol News 21: 343-44.