Hollywood Lesbians: Annamarie Jagose interviews Patricia White about Her Latest Book, Uninvited: Classical Hollywood Cinema and Lesbian Representability

[1] JAGOSE: Given the Motion Picture Production Code’s determination to corral “sex perversion” outside the cinematic field of vision, classical Hollywood cinema might not seem a promising archive for the consideration of lesbian representability. Can you talk me through what your book takes as its founding paradox, the Production Code’s prohibition against lesbian representation and classical Hollywood’s dissemination of lesbian meaning?

[2] WHITE: Hollywood films constructed and disseminated images of desirable femininity and worked consciously to address and solicit the desire of women in the audience. In the United States as many as eighty million people were attending films weekly in the 1940s – this enormous cultural power invested in women’s images and needs also shaped the lesbian identities that emerged in this period, even under the Code’s prohibition of “sex perversion or any inference to it.” It is a fairly familiar Foucauldian argument that censorship has productive effects – the Code favored particular narrative and visual codes, and lesbian representability extended beyond examples of “sex perversion” that censors could look out for and forbid. For example, it could be imbedded in women’s genres. Genre, with its way of structuring response through typical plots and iconic types, doesn’t require overt depictions, it relies precisely upon inference.

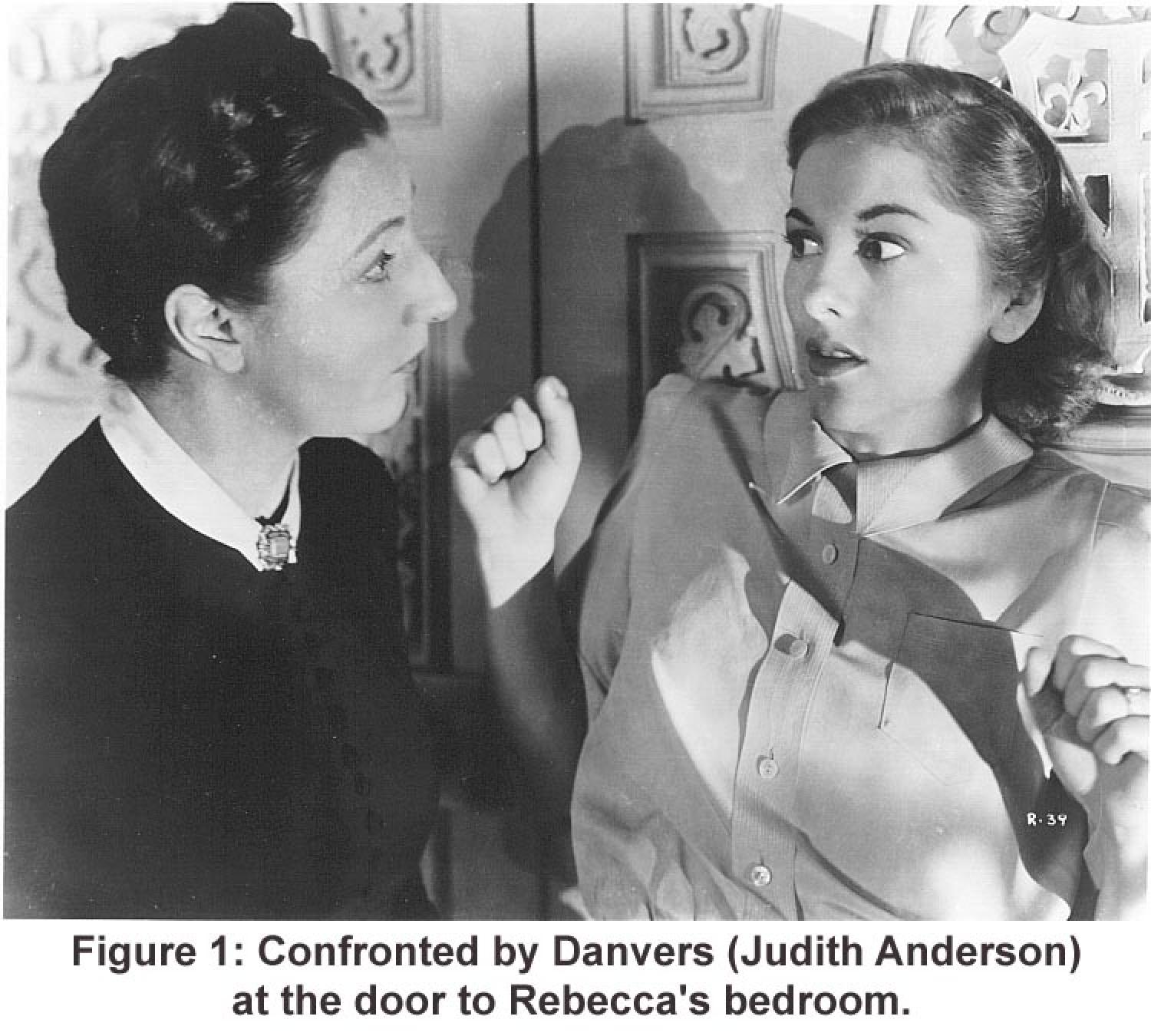

[3] WHITE: Take a film such as Rebecca whose

script the Production Code Administration actually did scrutinize for lesbian “inferences” (Rhona Berenstein has documented this). The film won the Oscar, not because it had been sanitized but because it put all of the sensual resources of Hollywood into adapting elements of an enormously popular, genre-defining woman’s novel (about maladjustment to marriage). It’s also a good example of the movies as “archive,” as you suggestively put it, because it condenses a number of strategies of representability. Mrs Danvers, the sinister housekeeper, is a recognizable and “unfeminine” visual type; the heroine is an unformed girl who parallels the audience’s own subjection to the “influence” of a woman. And Rebecca, the object of fascination, is literally unrepresentable, we have to rely on our imagination. [FIGURE 1] I think audiences were well trained de-Coders.

[4] JAGOSE: So does the concept of “inference” mark the difference between “representation” and – your favoured term – “representability”? Can you outline for me how a concept like representability works in relation to your argument about lesbianism and classical Hollywood cinema?

[5] WHITE: Yes, that’s right. Representability is a mouthful, but “representation,” implying that there’s lesbianism out there in the social world that could be “presented again” on screen just isn’t applicable under censorship and in dominant cinema. Lesbian desires and identities as we recognize them today were just taking shape at the time these films were made. Representability suggests some of the work of encoding and of decoding lesbianism that goes on in cultural forms – it designates the favored tropes that viewers have learned to recognize and that lesbian filmmakers today might even deploy for their own purposes. Freud uses the term representability when talking about how the latent content of dreams evades internal censors – concepts must find sensual, pictorial form to be capable of being represented. I liked that resonance with movies as well.

[6] JAGOSE: As you know, there is currently a good deal of debate about the historical emergence of lesbianism as a category of sexual identity and, in that historiographic context, the classic Hollywood period (1930-1968) is a fairly late dating for the cultural consolidation of lesbianism as an intelligible identity category. InUninvited, you argue for an attentiveness to “the institutionalization of female spectatorship and its potential coincidence with lesbianism as an emerging cultural identity.” On what grounds do you argue for the historic conjunction of lesbianism and female spectatorship?

[7] WHITE: The historical work you refer to is extremely valuable; I’m especially interested in what it tells us about how representations (sexological, literary, popular) contributed to that emergent identity – at the end of the nineteenth century and after. In my account of the classical Hollywood period, I’m not referring to an historically new lesbian sexual identity; rather I’m suggesting that a genealogy of our contemporary sense of lesbian cultural identity (essentially the position from which we view these films and read their subtexts) ought to include women’s pictures, female stars, and their reception contexts.

[8] JAGOSE: OK: so what significance do you attach to the simultaneous consolidation of lesbianism as an available cultural identity and classical Hollywood cinema?

[9] WHITE: In the United States in the 1930s, cinematic censorship was made official, while a discussion of lesbianism, already present, exploded in other venues from doctors’ offices to theaters to pulp novels. But it was the cinema that delivered weekly doses of desire to female audiences. The “homosocial” dimensions of spectatorship such as fandoms, like the “women’s worlds” depicted onscreen, were not at this point “innocent” of sexual possibility – lesbianism was a definite presence in the social formation. In retrospect, the movies “taught” us how to be lesbians even in the absence of lesbian characters – not only in individual encounters with gorgeous icons, but by (mass) mediating those encounters socially.

[10] JAGOSE: I’m interested in the way in which your last couple of responses – like your book – move between two scenes of spectatorship, that of the classic Hollywood audience and that of the contemporary audience for whom the pleasures of classic Hollywood cinema are importantly bound up with retrospection. How might lesbian representability be differently secured across those two scenes?

[11] WHITE: Certainly I’m interested in how lesbianism can be represented differently today, after decades of lesbian visibility and self-representation (including in film) than at the time of these films’ production – sex, subcultural verisimilitude, girls going to the prom together can be shown. Yet I’m also suggesting that representability as a concept depends on uniting, articulating together, what you have aptly called two “scenes”. I’m not writing as an historian; the conditions of the “encoding” of lesbianism in films like Queen Christina or These Three are reconstructed, decoded through the different repertoire that’s available to me. I wanted both to avoid and to address accusations of “presentism” leveled at gay/lesbian readings of historical cultural artifacts (“you’re just reading lesbianism into Dracula’s Daughter – she’s stalking that girl because she’s hungry“!). I don’t use the idea of subtext; instead I tried to theorize the critic’s (that is, the viewer’s) desiring look back.

[12] WHITE: In the concept of “retrospectatorship” I draw upon the psychoanalytic notion ofNachtraglichkeit, deferred meaning or retrospection, and upon Teresa de Lauretis’s work on fantasy and sexual structuring. An unconscious “scene” becomes meaningful in retrospect, it is opened onto and transformed by experience in the present. I think genre, and other ways cultural representations are given structural consistency, can work as a form of public fantasy.So for meThelma and Louisetaps into a lesbian fantasy scenario, but more realist – or diegetically or sexually explicit – lesbian depictions may not activate those same structures. If I’m extrapolating from the subjective to the social formation, it’s because fantasy moves between these two scenes – the “contents” of subjective fantasy are social. To make this more concrete: Mrs. Danvers was encoded as a lesbian inRebecca sixty years ago – the censors picked up on it, new biographies of Rebecca’s author Daphne du Maurier suggest her concern with lesbian desire. [FIGURE 2] Today’s viewers’ – possibly extensive – experience of similar representations might be drawn upon to access the film’s fantasy in part from that character’s perspective.

[13] JAGOSE: So your coining of the term “retrospectatorship” indexes, among other things, the unpredictable workings of fantasy across the field of meaning constituted between the film text and the individual spectator. As such, is retrospectatorship a tightly focussed description of the processes of spectatorship generally or does it have a particular resonance in relation to lesbian spectatorship?

[14] WHITE: While I do think the concept of retrospectatorship could have a more general application, I try to use this unpredictability of fantasy to overcome a particular block in feminist psychoanalytic film theory around lesbian spectatorship. In an essay first published in the early 1980s, Mary Ann Doane argued that women are failed voyeurs who are destined to “become” the image: “For the female spectator there is a certain overpresence of the image, she is the image.Given the closeness of this relationship, the female spectator’s desire can be described only in terms of a kind of narcissism – the female look demands a becoming” (Doane, Femmes Fatales, 22). Against this paradigm, I posit a kind of lesbian “second sight”– a look of desire, recognition and retrospection – to help us get a little distance from the model of overidentification. In a female genre such as the gothic, the heroine’s fear (of her husband, usually) is haunted by another scene, often by another woman. In the third chapter of my book, “Female Spectator, Lesbian Specter,” I trace a genealogy of films which work through this relation between ghostliness and lesbian spectatorship; the specter of lesbianism in a film like Rebeccadoubles in The Uninvited – there are two actual ghosts in this film, which is in many ways an explicit attempt to reproduce Rebecca‘s formula. By the time of The Haunting, we have a houseful of pretty scary ghosts complemented by a flesh-and-blood lesbian (played by Claire Bloom). [FIGURE 3] These figures are part of the same fantasy, in which desire and prohibition, pleasure and paranoia are mixed up in different degrees for different viewers.

[15] JAGOSE: Let me put aside for a moment the haunting quality of Hollywood screen lesbians. First, I want to talk some more about the theoretical impasse you mention that structures feminist film theory in relation to the (im)possibility of lesbian spectatorship. In your book, you write, quite densely and evocatively, that “Female spectatorship may well be a theoretical “problem” only insofar as lesbian spectatorship is a real one.” Can you unpack this sentence a little? What is the problem of female spectatorship and how do the structures of lesbian spectatorship raise those difficulties to the second power?

[16] WHITE: I argue that lesbian specters haunt both the gothic women’s picture and the “house” of feminist film theory itself. At the moment of its greatest intellectual coherence and influence, from Laura Mulvey’s work in the mid-70s through at least the mid-80s, feminist film theory also suffered from a case of what Monique Wittig calls “the straight mind.” Theorizing female spectatorship from an anti-essentialist position influenced by Lacanian psychoanalysis led to an impasse. Despite the radical critique of identity offered by psychoanalysis and poststructuralism in general, sexual difference was conceived heterosexually, and “woman” – though understood as a position, not a person – was the object, not the subject of desire. Vision was aligned with desire, and – presto! – the “female spectator” disappeared – “she” became a theoretical impossibility. Historical and empirical work on female audiences – who obviously looked, desired, identified, and enthusiastically – led to a revision of this orthodoxy, and my work was part of a critique mounted by a number of lesbian theorists in psychoanalysis’s own terms – your own work and that of Judith Roof, Judith Mayne and Lynda Hart among others. In feminist film theory, it sometimes seemed as if the – obviously anti-intuitive and counter-productive – insistence on the impossibility of female spectatorship was defensive. In my ghost chapter, I go so far as to link its rhetorical traces with the “defense against homosexuality” Freud argues is behind paranoia,the defense that provides some of the anxious and alluring atmosphere of the films I’ve I locate my book in its wake. mentioned. Not all women who look with desire at other women are lesbians, but lesbians do exist! For me this is a way not of dismissing this work on spectatorship as heteronormative but of reading its symptomatic omissions. Psychoanalytic feminist film theory was rigorous, persuasive, and exciting – and what an archive it was working with – Marlene Dietrich, Mae West, Bette Davis films! [FIGURE 4]

[17] JAGOSE: I like the way your argument about the gendered separation of the trajectories of desire and identification which structured an influential strand of feminist film theory pulls together the (feminist) critique and its (classical Hollywood) object by diagnosing the similarity of their symptomologies, their insistent summoning of lesbian spectres. You mentioned earlier a connection between ghostliness and lesbianism which is legible across an archive of horror films. How does the figure of the ghost or the scene of its haunting articulate with your larger argument about lesbian representability?

[18] WHITE: There are literal and figural connections. Seeing ghosts in a number of films that had lesbian overtones– most notably in The Haunting– is what inspired me to undertake this project and to work with the concept of representability. Hollywood censors wanted the studios to conform to the “spirit” as well as to the letter of the Production Code; yet literal spirits seemed able to get around the Code’s prohibition against homosexuality. Ghosts aren’t simply re-presentations; they appear as a result of what Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams called “considerations of representability”– they are mediated, visual manifestations of thoughts, wishes, prohibitions (375). As a trope of absent presence/present absence, the ghost illuminates the theory of homosexuality as the excluded, abjected other against which heterosexuality constitutes itself as norm. Classical Hollywood cinema is relentlessly heteronormative; homosexuality as a “structuring absence” is manifested in the ghost. Horror links fear and desire, it explores the lure of the supernatural– the “unnatural”– and Hollywood ghosts seem to have a particular affinity with lesbianism (rather than with other “unmentionables” such as racial others or male homosexuality). Perhaps this is because modern ghosts tend to haunt houses, and the domicile is associated with femininity.

[19] WHITE: This is certainly the case in the films I explore. InThe Haunting, the ghosts are female– the architect male– and the house itself is sexualized, threatening, alive. Shirley Jackson wrote the 1959 book upon which the film was based, The Haunting of Hill House. Like Daphne du Maurier, author of Rebecca , Jackson explored the association between lesbianism and the supernatural in several of her works. Unlike more corporeal monsters, ghosts allow an oblique strategy of representability, one that eludes patriarchal visual capture and objectification. We see ghosts with what Monique Wittig calls an “out-of-the-corner-of-the-eye perception,” rendered in the films by camera and editing techniques (Wittig, 62). But the ghost is also a figure of prohibition. Paranoia, rendered through visual and auditory hallucinations, works as a defense against homosexuality in these female authors’ works and in the films that are adapted from them. The violence of “the haunting” registers homophobia as well as homophilia. Danvers dies in Rebecca; the heroine of The Hauntingalso dies; both stay on to “haunt” the houses with which they are identified. The different supernatural effects in The Uninvited are ultimately attributed to the two female ghosts, defined in polar opposition: one makes the heroine feel warm all over, the other’s iciness makes the heroine pass out and finally attempt suicide.

[20] WHITE: The ghost film may elude the association of femininity with “presence,” with a visibility that is subject to (male) mastery or knowability. But this very invisibility allows the possibility that I’m just “seeing things,” or it supports a variation of the Lacanian dictum on “woman”: “the lesbian does not exist.” Finally, since ghosts are disembodied there’s no sex in these films, just shivers. Flesh-and-blood lesbianism appears in other genres– vampire flicks, pornography. Yet something is there in these films, hinted at through cinematic strategies of representability, even though lesbianism is not “represented.”

[21] JAGOSE: Since we’re talking about the ways in which particular generic conventions enable different articulations of lesbian desire – the eroticised haunting of the ghost film, the more carnal transfusions of the vampire movie – perhaps we can turn to your work on the woman’s film, in particular the maternal melodrama. Of this seemingly more anodyne genre, you argue “Rather than offering explicit depictions of lesbianism, the genreaddresses – in both sense – women’s desire for women.” How does this reading of the maternal melodrama intervene in the more traditional feminist critical take on the genre?

[22] WHITE: I really see the argument of the entire book as engaging with the lesbian dimensions of the woman’s film and with the copious feminist criticism on that genre. Mary Ann Doane’sThe Desire to Desiredefines several subgenres of the woman’s film – the cycle of ghost/gothic films I discuss is related to her category “the paranoid woman’s film.” Even these films feature intensely Oedipal scenarios and in this way set up my discussion of the lesbian elements of the maternal melodrama (another category Doane discusses) in a chapter I call “Films for Girls.” If it is true, as Doane suggests, that women’s pictures attempt to address women’s desire, in the sense of talking about it and soliciting it, then it makes sense that the maternal, a primary way of defining the feminine in patriarchal culture, is such a central discourse in them. It also makes sense – and this what has not been talked about – that the difficulty with defining women’s desire that feminist critics see as a central preoccupation of genres addressed to women arises in part because that desire is too narrowly restricted to maternal and/or heterosexual scenarios. In other words, the maternal melodrama is also about the fantasy of being – having – “something else besides a mother” to quote a memorable line from Stella Dallas – just as the romance can be about wishing for an alternative to heterosexuality.

[23] WHITE: The female familial dynamics of women’s pictures are extremely perverse, and enjoyably so. The maternal melodrama is derived from nineteenth-century fiction and drama and has remained popular throughout Hollywood history. In the 1930s, major female stars played sacrificial mother roles (Dietrich inBlonde Venus for example), sometimes in order to shift focus away from the sexual indiscretion that might have resulted in the heroine’s having the child in the first place and thus to evade the censors. But the result was that the relationship with the child took precedence over the relationship with the male co-star, and this enabled an intense investment in the female star through identification with the child’s position. Of course this is an oedipal or pre-oedipal desire, but it is reducing the variety and intensity of these films to say it isn’t also sexual as well as socially and aesthetically mediated.

[24] WHITE: I was interested in dislodging what I saw as a hegemonic emphasis on the maternal in feminist psychoanalytic theory. While it is important to “rescue” the mother from the obscurity and lack of power to which Freudian theory may have consigned her, there’s a risk of subsuming anything going on between women to the maternal and thereby negating it. It is especially difficult to extricate a psychoanalytic account of lesbian desire from a “scientific” and popular legacy of thinking of lesbianism as immature or a maternal fixation and indeed from well-intentioned feminist “solidarity” models that attempt to bypass the sexual nature of lesbianism and equate desire between women with “female-bonding” or the preoedipal attachment to the mother. Yet to refuse to touch the maternal melodrama for fear that one’s account could be assimilated to this non-sexual version would be to turn away from the perverse provocations of the women’s picture. By taking on films that are literally about mothers and daughters, I wanted to do the opposite of collapsing lesbianism into the maternal. I wanted instead to draw out the potential of the maternal as an available trope upon which lesbian scenarios are based. For example, intergenerational relationships – like the pedagogical – are a mainstay of lesbian fiction and of film classics such as Maedchen in Uniform. They “queer” or pervert maternal discourse. And by the 1940s, women’s films had become very ambivalent about mothering and about sororal bonds; I think this is because familial scenarios had become pretexts for stories the films couldn’t tell directly.

[25] WHITE: This is all fairly abstract. Let me start again from my point of departure in the book – Bette Davis in Now, Voyager. This is the mommy of all women’s pictures for me. I respond to it very viscerally as a lesbian film even though the heroine doesn’t have a significant relationship with another adult woman (as Davis’s characters do in a whole host of other films of the period). It’s a case history that ends with a different kind of “happily ever after.” “I shall get a cat and a parrot and live alone in single blessedness,” the heroine jokes at one point – and she ends up with a 12-year-old girl. She famously refuses her male lover, the girl’s father – “Don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars” – and many readings of the film’s ending celebrate this refusal (though many others bemoan the heroine’s “sacrifice”). Now, Voyager is a maternal melodrama from the daughter’s perspective – she escapes her mother, separates from her conservative will. But the heroine recreates that relationship with the girl Tina and revises the maternal in the process. I call it a governess fantasy – The Sound of Music is a lesbian film in the same way!

[26] WHITE: I think the genre itself is engaged in a revision of maternal discourse and of oedipal fantasy – I emphasis the link between genre and generation. Through a queer form of reproduction – you might even call it pedagogy – new fantasies are enabled, viewers are taught to see differently. For example,Now, Voyager is the culmination of a whole cycle of Bette Davis women’s pictures of the period, such as The Old Maid and The Great Lie, which offer permutations on the fantasy of having two mothers or “something else besides a mother.” In the last chapter of my book, I return to this queer idea of how private fantasy and public genre are linked through revision in my consideration of a later – and very different – intergenerational quasi-lesbian Bette Davis film, All About Eve.

[27] WHITE: Although there is a great deal of fine historical work and criticism on the maternal melodrama, most feminist scholarship tends to look for the “truth” of the mother or of the mother-daughter bond. I’m more interested in the fiction – and the genre gives us some twisted tales! On one level the woman’s picture expresses a utopian vision of a female world; I believe that there is a sexual element to the affect and excess so characteristic of the genre.

[28] JAGOSE: Although so far we have been talking about stars, the forceful centre screen presences of Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich and Mae West, you argue that lesbian signification frequently inheres in those less numinous supporting characters whose marginalisation constitutes for the spectator a kind of cinematic peripheral vision. How do you read the ideological work of the supporting character?

[29] WHITE: I focus on the periphery of the film’s action or mise-én-scène because often there is a critique of the status quo being mounted there. It can be as literal as a character who makes wisecracks about the central romance or as subtle as a fixed gaze from a peripheral character to the lead, perhaps anchored by the “mannish” way that character is dressed. I look at specific characters and actors and at fleeting moments of critique, but also at the more systemic function of such characters. Hollywood cinema is a very codified world, narratively and visually. Structurally, such characters “support” the primary storyline – invariably some version of heterosexual romance – and thus their marginalization also supports heteronormativity and the linked conservative ideologies that govern Hollywood fictions. Think of how often supporting characters have to die to bring the heterosexual couple together.

[30] WHITE: In art films and later in Hollywood when gay and lesbian characters are identifiable as such, they are restricted to supporting roles – a film like My Best Friend’s Wedding is almost a meta-commentary on this phenomenon. Nevertheless, through this compulsory – compulsive? – sidelining, the fact of marginalization itself is legible. For example, it is only on the margins that non-white women and women of different body types and class statuses can exist in classical Hollywood – the maids and the secretaries, the shopgirls and the prison matrons. Such figures both contrast with and also often seem to “couple” with the white leading ladies with whom they are paired in the frame – sometimes the exaggerated contrast looks like butch-femme coding. (I think this contrast works more vividly with female leading-supporting pairs than with male ones precisely because it is leading actresses who are supposed to be the focus of the sexualized gaze). Here I get close to a practice I’m actually quite wary of – “reading in” lesbian/gay significance to “benign” scenes, or into configurations that are about something else – say racial hierarchy. But I actually think that classical Hollywood is so resolutely apolitical and individualistic in how it deals with social and ideological contradictions, that it often has no other way of signifying difference than sexualizing it. I think here of James Baldwin’s scathing analysis of the mulatto characters’ sexual personae inThe Birth of a Nation.

[31] WHITE: The repetition of certain practices of type-casting, the proliferation of certain immediately recognizable role, generates its own story; this intertextuality interrupts the drive towards heterosexual narrative closure in individual films. At the end of Dark Victory, the dying Bette Davis has sent her uncomprehending husband away and she shares a wrenching moment with Geraldine Fitzgerald, her all-comprehending best friend – and finally her loyal, silent housekeeper is the last one there. These women are surrogates for the weeping female viewer, but the physical presence of bodies in proximity on screen sometimes makes us forget the plot’s attempts to give plausible reasons why two women are sharing such intimacy.

[32] JAGOSE: Given that many of the actors you discuss – Ethel Waters, for example, or Agnes Moorehead or Mercedes McCambridge – become associated with particular kinds of supporting characters, do they accrue a sort of second-order star iconicity that facilitates a lesbian reading such as yours?

[33] WHITE: Yes, absolutely. Even more than the narratological/structural function of these characters, their subversiveness is performative. That is, it is very much dependent on the specific actor’s performance in the role and the meanings that accrue to their image from other, similar roles and from what we might know about their “real lives” – the inter- and extratextual dimensions of any given moment. The subversiveness is also performative in the sense that speech-act theory accounts for doing things with words – or looks or gestures. Supporting characters are part of other entertainment traditions – they are often not successfully subordinated to the dictates of narrative verisimilitude.

[34] WHITE: Who pays attention to these performative dimensions – who recognizes what’s going on in the background?One example would be how African American audiences have been able to “see” African American actors in the context of their work outside mainstream Hollywood film – and thus to “see” their marginalization. Ethel Waters conveys so much more than her “mammy” screen roles as written – her hard-luck and her Harlem nightclub stories, her recording and Broadway successes all might filter audiences’ reception of her performances. [FIGURE 5] A performer like Mercedes McCambridge was used iconically by Orson Welles; he wanted her to play butch in Touch of Evil. But ultimately who pays attention to all of these stars is gay men. Whether it is Margaret Hamilton as the Wicked Witch of the West or some long-forgotten child star or a sissy floorwalker, there is camp appreciation for their uniqueness. In his influential bookStars, Richard Dyer – and it is crucial that he’s gay himself – discusses how particular star images catch on because they represent an imaginary resolution to a contradiction in social roles (stardom in general is most notably about the contradiction between the ordinary and the extraordinary). Supporting characters’ images tip the balance – they don’t have to resolve a contradiction – they can be purely shrew or slut or servicewoman.

[35] WHITE: The chapter I wrote on supporting characters is for a me a tribute to gay male writers,audiences and scholar fans – the followers of Joan Blondell, the wisecracking golddigger in 1930s film. There, I pay tribute to writers like Vito Russo, Quentin Crisp, Boyd Macdonald, James Robert Parish, and Michael Bronski – some of whom write, or wrote – popular or even sleazy film books and some of whom are very prominent gay activists and writers. I allow myself to gush a bit in this chapter to make my admiration for these performers – and their hagiographers – palpable, though I also try to theorize “gush.” I think that information about classical Hollywood stars, and viewing attitudes towards them, are often conveyed to lesbians via gay male cinephile/camp culture. I wanted to acknowledge that connection while exploring differences in lesbian appreciation historically. The latter tends to be more literal-minded – even clueless! – but is perhaps more attuned to the misogyny of a spinster character (such as the ones Agnes Moorehead played) – or to the sexual frisson that might bypass a gay male camp reading and appeal directly to lesbian lust or identification. [FIGURE 6]

[36] JAGOSE: Speaking of lesbian identifications, early on in your book, you discuss the lesbian appropriation of classic Hollywood imagery. I am thinking here of your discussions of Deborah Bright’s “Dream Girls” series in which the artist resignifies the archetypally heterosexual Hollywood still through the insertion of her own legibly butch image or Cecilia Barriga’s video compilationMeeting of Two Queensin which the techniques of editing engineer an affair between Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. What are the implications of these engagements with the artifacts of Hollywood for your arguments about lesbian spectatorship?

[37] WHITE: In a chapter called “Lesbian Cinephilia,” I explore one mode in which contemporary artists have negotiated lesbian representability now that lesbian representation – depicting dyke communities or women who fall in love or have sex with each other – is possible. They borrow from classical Hollywood – its iconography and its ways of seeing – in imagining what lesbianism can look like, and in this their practice as artists actually makes visible what lesbian spectators do unconsciously. As the term “cinephilia” suggests, a key concept here is fetishism. I discuss a number of contemporary lesbian photographers, filmmakers, and video artists who use Hollywood artifacts – glamor photography, film clips, and star lore – as fantasy fragments in their work. I think it is emotion that differentiates this strategy from the citationality of postmodernism more generally as well as from camp. Rather than achieving a distance that emphasizes the surface or the form of an image from the past, there is a surrender to its spell, a rehearsal of its charms. Even the most cliched images are cathected.

[38] WHITE: Deborah Bright’s wonderful series “Dream Girls” literalizes the concept of fantasy as “mise én scène of desire.” She pastes her own image into a series of film stills featuring stars of her personal pantheon, playing now against then, still against moving image. With a butch in the picture, the girls become lesbians, but the series also shows how heavily influenced butch styles have been by Hollywood glamor, male and female. I discuss Bright’s series in the context of an exploration of which stars captured lesbians’ erotic imaginations and why. This is something lesbians never seem to tire of discussing! Bright makes visible the mechanics of fetishism, foregrounding aspects of Katharine Hepburn’s complicated persona in several images. Hepburn could be butch or feminist – but she was trapped by her association with Spencer Tracy, something Bright captures by depicting herself as the couple’s chauffeur. Hepburn, like Garbo and Dietrich, is an “overdetermined” lesbian icon – their images evolved through significant interaction with lesbian history and styles.

Images from the 1930s of these three cross-dressing are cited so often by lesbian artists and in gay and lesbian visual culture more generally that they no longer give one a particular aesthetic experience so much as remind one of the history of lesbian appropriation of Hollywood images. Barriga’s video could be understood as fleshing out that history. It is made up entirely of clips from Dietrich and Garbo films – it incorporates the familiar girl-girl kisses from Morocco and Queen Christina into a highly plausible narrative of love and loss that shows how the two stars’ images, and the characteristic love scenarios of their films, incorporated tropes of lesbian representability – demimondaine, invert – that circulated in the early 1930s. [FIGURE 7]

[39] WHITE: It makes sense that the “lesbian chic” of the early 1930s could be so effectively mobilized in the early 1990s when that term was bandied about in the mainstream media – what’s changed is that today lesbians are constructing a public discourse. I recently came across a 1934 Vanity Fair prototype for Barriga’s videotape; it’s billed as “a composite portrait” of Garbo and Dietrich, and it superimposes two Edward Steichen images so that the stars appear poised to kiss. I found the image in a file of Garbo clippings collected by Mercedes de Acosta, an American of Spanish descent and herself a sartorially extravagant butch. She met Garbo and vacationed with her idol at an isolated mountain lake in 1931 – when Garbo left for Sweden early in 1932 de Acosta had a rebound affair with Marlene Dietrich. Even though de Acosta lived the ultimate fantasy of lesbian spectators, her having clipped this image shows that her relationships with the stars were mediated by the screen, just as ours are. Cecilia Barriga, a Spanish artist, could be considered a latter day de Acosta, and Deborah Bright might be proud of how de Acosta found her trousered way into a few paparazzi photos of Garbo. The point is that these 1990s lesbian artists, by rendering such lesbian cinephilia in their work, have found a way to make the spectator’s desire, and thus the ordinary lesbian herself, visible.

Works Cited

- All About Eve (Joseph Mankiewicz, 1950).

- All This and Heaven Too (Anatole Litvak, 1940).

- Baldwin, James. The Devil Finds Work. New York: Dell,1976.

- Berenstein, Rhona. “Adaptation, Censorship, and Audiences of Questionable Type: Lesbian Sightings inRebecca (1940) and The Uninvited (1944).” Cinema Journal 37: 3 (Spring 1998), pp. 6-37.

- The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915).

- Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

- Dark Victory (Edmund Goulding, 1939).

- De Lauretis, Teresa. The Practice of Love: Lesbian Sexuality and Perverse Desire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

- Doane, Mary Ann. The Desire to Desire: The Woman’s Film of the 1940s. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1987.

- ——. Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Dracula’s Daughter (Lambert Hillyer, 1936).

- Du Maurier, Daphne. Rebecca. London: Gollancz, 1938.

- Dyer, Richard. Stars. London: BFI, 1979.

- Freud, Sigmund. Interpretation of Dreams. New York: Avon Books, 1965.

- The Great Lie (Edmund Goulding, 1941).

- Hart, Linda. Fatal Women: Lesbian Sexuality and the Mark of Aggression. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- The Haunting (Robert Wise, 1963).

- Jackson, Shirley. The Haunting of Hill House. New York: Penguin, 1959; rprt. 1987.

- Jagose, Annamarie. Lesbian Utopics. New York: Routledge, 1994.

- Maedchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, 1931).

- Mayne, Judith. The Woman at the Keyhole: Feminism and Women’s Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

- Meeting of Two Queens (Cecilia Barriga, 1991).

- Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930).

- My Best Friend’s Wedding (P.J. Hogan, 1997).

- Now, Voyager (Irving Rapper, 1942).

- The Old Maid (Edmund Goulding, 1939).

- Queen Christina (Rouben Mamoulian, 1933).

- Rebecca (Alfred Hitchcock, 1940).

- Roof, Judith. A Lure of Knowledge: Lesbian Sexuality and Theory. New York, Columbia University Press, 1991.

- The Sound of Music (Robert Wise, 1964).

- Stella Dallas (King Vidor, 1937).

- Thelma and Louise (Ridley Scott, 1991).

- These Three (William Wyler, 1936).

- Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958).

- Uninvited (Lewis Allen, 1944).

- Wittig, Monique. The Straight Mind and Other Essays. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992.