Participation Without Power: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Community Meetings in North Denver

Sabrina C. Sideris teaches with INVST at the University of Colorado Boulder where she helps people become skillful change-makers. She has a Ph.D. in Higher Education from the University of Denver. She researches how universities contribute to displacement and gentrification. She also helps develop affordable housing cooperatives in her community.

See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Universities help shape cities. Historical forms of racial domination repeat themselves, reproducing spatial subordination. In Denver, residences and businesses owned by families of color will be cleared as Colorado State University (CSU), two museums, and the mayor’s office redevelop the area to build an educational hub. An examination of Citizens Advisory Committee (CAC) meeting transcripts shows that relationships between the higher education institution and the city are changing in racialized ways, as normative institutions overpower low-income communities of color. Reading discursive events from CAC meetings through a theoretical lens reveals the CSU expansion to be an instance of a predominantly white institution working with city leaders to remove people from land so it can be used to better fulfill economic ambitions, exemplifying theories about the spatialization of race and the racialization of space (Lipsitz, 2006, 2007, 2011). This occurrence has implications for higher education researchers and municipal leaders beyond Denver.

Keywords: discourse, displacement, racialization, spatialization

Participation Without Power: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Community Meetings in North Denver

Introduction

Colorado State University (CSU) has begun construction on a new global campus in North Denver, more than 65 miles from its flagship campus in Fort Collins, Colorado. The CSU expansion will provide a place for the study of agriculture, sustainability, and water in the West. The new complex will build upon a partnership that CSU has had since the early 1900s with an entertainment facility for agricultural expositions: the National Western Center (NWC), home of the annual stock show. CSU’s new campus is envisioned as an educational and entertainment hub for Denver and a global destination for agricultural research, drawing scientists from all over the world and infusing the Colorado economy with added conventions and tourism (NWC Master Plan, 2015). In 2018, travelers to Colorado spent $22.3 billion on trips and vacations (Colorado Tourism Office, 2019). Along with increasing heritage tourism, agricultural tourism, recreational tourism, and cultural tourism, the new campus will “serve as an additional site for meetings, banquets, conventions and trade shows, adding to Denver’s ability to grow this $650 million industry” (NWC Master Plan, 2015, p. 48).

The CSU global campus, with facilities covering 250 acres near the intersection of Interstate 25 and Interstate 70, will be a place for discovering solutions to world problems. CSU also plans to improve access to the South Platte River, add bike lanes and running trails, and provide jobs and educational opportunities to the residents of surrounding neighborhoods (NWC Master Plan, 2015). But residences and small businesses owned by low-income immigrant families on 38 parcels of land will be cleared in order for CSU to redevelop the area. The CSU expansion is an instance of a predominantly white institution (PWI) working with city leaders to remove low-income people of color from land so it can be used to fulfill the state’s economic ambitions.

This study examines the relationships between higher education institutions and the cities in which they are located. I examine the process of relationship formation between a campus and the city to determine if and how race plays a role as those relationships form. By examining racial undertones in community discussions about CSU’s expansion, I hope to advance the study of the role that higher education institutions play in urban restructuring. I ask the following research question: How are relationships between the higher education institution and the city changing in racialized ways?

In this research project, I use Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to comb through transcripts from more than 60 Citizens Advisory Committee (CAC) meetings, focusing on moments of import that reveal how power moves in groups of people and how their words build a social reality. Higher education leaders ought to focus more attention on how expanding a campus impacts the social and racial dynamics in the city in which that growth occurs. Colorado State University leaders who are presiding over the expansion into Denver have made promises about the collaborative process by which various stakeholders will be working together to build the new campus (CSU Center, 2018; NWC Master Plan, 2015; Source Newsletter, 2017). That is the process I have placed under a microscope, in this paper.

Background and Context

The City of Denver, led by Mayor Michael Hancock, is engaged in multiple urban development projects simultaneously (Denver City Government, 2018), grouped together under the name North Denver Cornerstone Collaborative (NDCC). In addition to redeveloping the NWC while creating a new CSU campus, the NDCC will:

- Widen a 10-mile section of Interstate 70, lower the interstate between Brighton Boulevard and Colorado Boulevard, and build a park on top of it (called the “ditch project”)

- Redevelop Brighton Boulevard

- Redevelop the River North (RiNo) district

- Develop a new rail line to help commuters travel more efficiently from the heart of Downtown to the Denver International Airport (DIA) (NDCC, 2017).

These projects will cost more than $1.7 billion according to the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT, 2018a). Measure 2C, which voters passed in November 2015, raises those funds through a tax imposed on hotels and rental cars. In addition, House Bill 1344 gives CSU access to $250 million in state funding to build education and research facilities and expand the university’s programming to the NWC (Salazar, 2015; CAC Meeting Notes, April 30, 2015).

The neighborhoods where displacement will occur are called Globeville, Elyria, and Swansea (GES). Daniel F. Doeppers once described Globeville as an old ethnic community of working-class Mexican-American residents. In 1967, he wrote, “The partial destruction of seven residential blocks and the resulting truncation of the community by the construction of Interstate 70 ... has had a demoralizing effect” (Doeppers, 1967, p. 522). These three neighborhoods have not seen significant infrastructure investments in well over three decades (NDCC, 2018). The new project will continue historic trends of displacement; between 1961-1964, the initial construction of Interstate 70 between Colorado Boulevard and Interstate 25 resulted in the loss of 30 homes in this particular area (CDOT, 2018b). The NWC and CSU will need to acquire 38 more private parcels in order to fulfill their redevelopment plans (CAC Meeting Notes, January 26, 2017 & May 31, 2018). This acquisition amounts to 64 acres currently inhabited by working-class Latinx families and individuals (Tracey, 2016; Piton Foundation, 2018).

CSU is becoming a developer in one of the 20 fastest-growing cities in the U.S. according to the S&P/Case-Shiller national home price index (Delmendo, 2018). In a May 2018 CAC meeting, Saunders Construction presented their demolition plans to the NWC and CSU. They shared an eight-phase plan to remove businesses and homes to clear a path for building the new campus. Some of these doomed properties can be seen in the Appendix. Since this pattern of displacement recurs in other cities as postsecondary institutions grow (Chatterton, 2010; Etienne, 2012; O’Mara, 2012; Smith, 2009; Smith and Holt, 2007), this study can inform higher education research because it depicts an intertwined administrative process and social phenomenon that occur in multiple cities.

Displacement Caused by University Expansion

In Baltimore, Maryland, my family lived in Hampden and Remington, two different neighborhoods with a university perched in between. Both Hampden and Remington were working-class white neighborhoods when I moved away in 1996. My aunts, uncles, and my grandmother paid between $330 - $470 per month per household in rent. As the years passed, when I called home, I would hear story after story of displacement.

“Jean had to move. Her landlord raised the rent.”

“Why?” I asked my mom.

“They’re trying to push my sisters out because they can get twice as much from Hopkins students.”

The neighborhoods that raised my family stopped being affordable or welcoming to them in the early 2000s as Hampden morphed into a trendy and expensive area that catered to Johns Hopkins University. By now, the same process has started to happen in Remington. University expansion that causes displacement is certainly not unique to Baltimore or Denver. Columbia University in New York used eminent domain to remove people from their property and bulldoze part of Harlem in order to build a $6.3 billion expansion (Moore, 2013). Cooper, Kotval-K, Kotval, and Mullin (2014) write about the area between Columbus Avenue and Tremont Street, at the edge of Roxbury, an area in Boston that was razed by Northeastern University, just as the rise of the knowledge economy enhanced the value of universities to the cities hosting them. In “The Downside of Durham’s Rebirth,” White (2016) describes Duke University’s role in remaking the city. Although unsightly vacancies were removed, so was affordable housing for Latinx and low-income families who had been long-time Durham residents. In Philadelphia, Temple University is currently in the midst of a growth spurt (WhatsPOPPYN, 2017). That expansion comes with an increase in the size of the university police force; there is a positive correlation between the presence of college students and increased surveillance of Black and brown communities (see Ferman et al., this issue).

Sometimes, the university’s expansion into the city is perceived as a rescue mission. Pittsburgh was reckoning with the collapse of the steel industry when Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh became major players in the city’s rebirth as a high-tech city, through a partnership with government, business, and the philanthropic sector (Ferman, 1996). In Boston, through a partnership between university staff and neighbor representatives, a harmonious town/gown relationship was created through a 50/50 split of the land that had been cleared for redevelopment: half the new units were built for university students and the rest were owner-occupied affordable housing for Roxbury residents, helping all parties thrive (Cooper et al., 2014). As Johns Hopkins University reshapes Baltimore, University President Ron Daniels says,

You can make the moral case of why, given the bounty of resources that we have, it’s incumbent on us to share with the city. But the other thing is to make clear that this is an enlightened form of self-interest. It is inconceivable that Hopkins would remain a pre-eminent institution in a city that continues to suffer decline (Mitter, 2018).

While some call this displacement process gentrification, Daniels considers the transformation of an 88-acre zone in East Baltimore to be a gift to the city and its diverse families and neighbors. The campus expansion that is currently underway will create, along with new research facilities for Hopkins, a new public school for the surrounding neighborhood, a restored park, job training programs, and more than 700 homes for mixed-income families, while attempting to breathe life back into an area of Baltimore that has suffered high crime rates and disinvestment (Mitter, 2018).

Colleges and universities can be assets to their communities, given proper planning with the community (Fox, 2014). If mechanisms are established to review and monitor social, economic, cultural, and physical changes in the community, the university and community can thrive together in a shared space (Fox, 2014). However, six years of CAC meetings in Denver attended by multiple stakeholders failed to produce effective mechanisms for CSU to honor the GES neighborhoods. Higher education leaders ought to create deeply democratic, anti-racist meeting processes. Universities that rebuild a city or region, while shoring up their own institutions (O’Mara, 2012), must do so without changing the ethnic and cultural character of urban neighborhoods and pushing out low-income people of color.

Studying Up

At first, this article was conceived as part of a multi-city study of the roles that higher education institutions play in displacement. While my study would focus on changing North Denver, within the same paper, other researchers would examine St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Santa Cruz. Together we would provide before, during, and after illustrations of how communities resist gentrification by colleges and universities. But when our peers read an early draft, they advised us to pare down the scope of our project. Four separate scenarios felt like too many for one article, so we separated out some of the cases. Now that mine stands alone, it can be read as a before illustration. The story I am telling is about a university that has spent more than six years planning a public-private partnership to redevelop a region of Denver, but construction only recently began on April 24, 2019. Displacement is inevitable (Tracey, 2016) and community resistance to gentrification has been occurring (GES Coalition, 2017). But my particular study focuses on the stages that take place before university-community partnerships form to resist gentrification.

It is common for people with access to normative institutions and their resources to study those without that access; researchers study disempowered people, further disempowering them in the process (Battiste, 2013; Patel, 2016; Smith, 1999). The contrasting practice of “studying up” comes from Laura Nader (1972), an anthropologist who examines the exercise of power and responsibility through administrative processes. One can ask questions about how and why powerful institutions function the way they do. Studying institutions that affect people’s everyday lives can help us develop theory (Nader, 1972) and by doing so, examine social and racial patterns that may be recurring from one city to another.

In this study, I examined the discourse of institutional leaders from a PWI. CSU leaders such as Amy Parsons, the Executive Vice Chancellor of the CSU System, have claimed to be engaged in a collaborative partnership. Parsons said, “Throughout the next several years the neighboring communities, project partners, civic and government leaders, and nonprofits will work together to build a campus” (Source Newsletter, 2017). Following her promise, CSU representatives have attended CAC meetings and participated in a public process to ultimately determine how GES neighborhoods will be permanently transformed by CSU’s expansion. But has it been a collaboration among equal partners? I argue that it has not.

Denver has much to learn from cities like Philadelphia and Santa Cruz, where university partners have co-created and evolved a set of tools and strategies for deep collaboration with the community as they resist displacement together. Before developing such community-based research (CBR) partnerships in Denver, studying up is an important step. Studying up can solve one of the dilemmas of CBR—researchers over-taxing community organizations. GES is a region of the city that has been surveyed, tested, photographed, researched, and recorded, while urgent needs like remediating lead contamination in the soil remain unfulfilled (U.S. EPA, 2019; CAC Meeting Minutes, March 12, 2015; April 30, 2015; February 25, 2016; January 26, 2017; September 14, 2018).

How will my research do anything more than bother folks who have already had so many promises made and broken (CAC Meeting Minutes, April 30, 2015)? How can I be sure an intervention or action will do more to help than harm? I use Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of the CAC meeting transcripts to ask a set of questions of a text about the way that social life is being organized. Who benefits from the way that social life is arranged and how could it be arranged differently? CDA facilitates studying up before taking the step to do CBR.

Theoretical Framework

Theories of the spatialization of race and the racialization of space interrogate how and why people of different races in the United States become relegated to different physical locations (Lipsitz, 2006, 2007, 2011). The factors that cause this to happen are historical, structural, administrative, institutional, and legislative. These factors include housing and lending discrimination such as redlining; zoning regulations; school district boundaries and the links between public school quality and property taxes; security, surveillance, and policing policies and practices; and public transit and connectivity. The racial makeup of the places where people live their daily lives exposes them to rewards and opportunities, as well as risks and challenges. There is a socially shared system of exclusion and inclusion that corresponds with the nation’s racial hierarchy, and with physical places. Relationships among race, place, and power stretch back to the founding of the United States.

Race and place determine who has access to certain life chances. The ability to accrue wealth and pass it down to subsequent generations; to own a home that will appreciate in value; to grant one’s children access to education and employment opportunities as well as physical health, safety, and security; to be surrounded by a clean and safe natural environment—these are spatial privileges that have been systematically granted to white people more often than to People of Color. Meanwhile, to be exposed to environmental hazards such as lead poisoning; to have unsightly or loud train tracks in close proximity to one’s home, with bleating horns, bright headlights, and loads of natural resources being carried to elsewhere; to find one’s neighborhood cut down the middle by the construction of a new highway, as is the case in North Denver—these are realities disproportionately faced by communities of color. In sum, people of different races in the U.S. live different spatial lives (Lipsitz, 2006, 2007, 2011).

George Lipsitz writes, “communities of color have experienced social subordination in the form of spatial regulation” (Lipsitz, 2007, p. 8). Systematic discrimination that has existed for generations prevents People of Color from acquiring assets that appreciate in value. Even when families and neighbors of color have the means to do so, it is more challenging for them to move to desirable neighborhoods with amenities and high-quality services including thriving public schools, because of racial discrimination by realtors, lenders, and insurance agencies. Not only do families of color find it challenging to move into areas of the city where they do want to live, but they also are removed from their homes and communities at a higher frequency than white families and neighbors. Urban renewal projects disperse communities of color, undermining the equity they had built in their homes and businesses and disrupting the social and communal routines from which happiness and mental stability were derived (Fullilove, 2004; Lipsitz, 2007).

As a result of systematic discrimination, “the placemaking practices of urban blacks differ from those of the white middle class” (Haymes, 1995, p. xiii). To describe and explain these differing placemaking practices, Lipsitz uses these terms: the Black spatial imaginary and the white spatial imaginary (Lipsitz, 2006, 2007, 2011). An imaginary is a set of values and priorities that guide the way a particular social group self-organizes. According to Lipsitz, the Black spatial imaginary emphasizes use value; it focuses on what people can do with or in the places they occupy. Lipsitz calls this defensive localism: it forms in places where people have been living with adversity and figuring out how to thrive in spite of disinvestment and political and economic abandonment. The Black spatial imaginary is characterized by mutual aid societies, often informal and unofficial, where neighbors help each other meet needs as they arise and pursue forms of self-help. When a GES neighbor who is a CAC member describes how people use space to socialize, she tells about hosting parties for decades as an Avon lady and she places emphasis and value upon knowing all her neighbors (Bettie Cram Oral History, 2013). This exemplifies an imaginary that “transformed these resorts of last resort into wonderfully festive and celebratory spaces of mutuality, community, and solidarity” (Lipsitz, 2011, p. 51).

According to Lipsitz, there is a contrasting way that predominantly white groups of people imagine themselves as part of a social whole. The white spatial imaginary emphasizes exchange value. Economic development is the central aim of the white spatial imaginary (Lipsitz, 2011), which is fixated on increasing the property value of the space. Privatization and exclusivity are typical in neighborhoods with more race and class privilege. My study explores the degree to which normative institutions structure society according to the white spatial imaginary. In North Denver, I interrogate CSU’s role in racially re-organizing the city.

Lipsitz’ theory is applicable not just to Black communities but to other communities of color as well. He argues, “all communities of color have experienced social subordination in the form of spatial regulation” (Lipsitz, 2011, p. 52). Examples in the U.S. include the Trail of Tears, the creation of reservations, Japanese internment camps, and the theft of Native American and Mexican lands (Lipsitz, 2011). There are many examples of white supremacist uses of space that have affected non-Black communities of color. Theorizing the Black spatial imaginary holds the possibility to create new life chances for all people, not just Black communities. Theories of the spatialization of race and the racialization of space were applied to this instance of CSU, a PWI expanding into three neighborhoods of color. I examined the CAC meeting transcripts to see whether discursive strategies worked to create or sustain racialized hierarchies in North Denver.

Research Literature

In addition to Lipsitz, I relied on other literature as I examined the CAC meeting transcripts through this theoretical lens. Fine et al. (2004) argue, “The production and maintenance of white privilege is a difficult task. … Racial hierarchies work with and through … institutional life to produce and sustain power inequities” (p. viii). The Philadelphia Negro by W.E.B. DuBois (1899), an ethnography of the Black community in Philadelphia, rejected assumptions about inherent racial differences, refused to fault individual Black people for challenges they experienced, and instead drew attention to structural inequalities imposed and upheld by whites. Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton’s book American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (1993) explained how racial isolation was manufactured by white people through a series of purposeful institutional arrangements when they wrote, “Segregation concentrates poverty to build a set of mutually-reinforcing and self-feeding spirals of decline” in neighborhoods of color (Massey & Denton, 1993, p. 2). Cultural anthropologist Melissa D. Hargrove’s work on the collection of skills, techniques, and capacities that institutions use to claim, distribute, and redistribute capital focuses on power struggles and strategies for domination and control. For example, the leaders of institutions know and use laws related to finance and real estate in order to grow their power and control within cities, counties, and the state (Hargrove, 2009). These scholarly works helped me learn to read the CAC meeting minutes through a theoretical lens focused on the racialization of space and the spatialization of race.

Methods

Language is used to construct particular realities during an administrative process of decision-making and action-taking among multiple actors, extending across a number of years. The higher education institution under study is opening doors for itself. In the process, other doors are being closed as it gains a very particular identity as a university. How members of the campus community will interact in the future with residents of surrounding neighborhoods hangs in the balance. Through this process, CSU is co-constructing a new social reality in North Denver that will have ramifications for how people will be able to live together and share the city. This study focuses attention on institutional actions that will be, once time moves on, buried amongst the roots of the social and racial reality that will – in the future – characterize this particular place.

After studying the words that contribute to the genesis of a particular racialized world, one can better identify the moments of import in that administrative process upon which other decision-making will hinge, and then one can more skillfully intervene and act to transform that imperfect, socially stratified world. Critical Discourse Analysis is the best method for this study since it focuses on such moments of import and enables the study of the way power moves in groups of people by attending to their words and the effects of those words on building a shared social reality. Through CDA, I seek to understand the phenomenon of the university’s contribution to re-shaping a city.

Examining language, which is a fundamental part of social life, can allow us access to act to transform the social world. As CSU enters North Denver, I have used the public archives from Citizens Advisory Committee (CAC) meetings about the National Western Center’s redevelopment process to unearth competing discourses by CSU, the mayor’s office, multiple developers and subcontractors, as well as those who live in Globeville, Elyria, and Swansea neighborhoods. I identified and traced both dominant and resistant discourses. The dominant discourse is that the institutions can better use property because they can make it more economically productive. The resistant discourse opposes displacement and gentrification. Conflict and tension arise because discourse is a site for both the construction and contestation of social meaning.

Research Questions

Since social, racial, and even spatial reality are constituted in part through discourse, I explore these focus questions in my study: In the context of the Colorado State University partnership to redevelop the National Western Center in North Denver, how is the college-community relationship unfolding? And in what ways is the relationship between the institution and the city being racialized?

Generating Data

I considered the public archives representing the six-year process of meetings with the GES community about the campus redevelopment. This process is still under way, as monthly meetings continue taking place. Meeting transcripts dating back to October 1, 2013 are available at http://www.nwc-cac.com/documents.html and maintained and updated by CRL Associates, a consulting firm describing themselves as “experts in public decision-making and experts in the world where communities, public servants, and organizations meet” (CRL, 2018). By reading the proceedings at more than 60 CAC meetings and listening to audio from one meeting, I found themes and patterns that reflect George Lipsitz’s theory.

Analyzing Data

I reviewed all transcripts once, then performed a second close reading, pausing to create codes. During my second reading, I searched the data for predominant themes and patterns that either exemplified or defied Lipsitz’s theory of the spatialization of race and the racialization of space. I relied on Saldaña’s explanation of how this is done: “In qualitative data analysis, a code is a researcher-generated construct that … attributes interpreted meaning to each individual datum for later purposes of pattern detection” (Saldaña, 2016, p. 4). Some examples of codes that pertain to space and race include “infrastructure improvements,” “land acquisition,” “property value,” “use value,” “what neighbors want,” and “outside expertise vs. local wisdom.” In addition, I coded the words, phrases, and moments between meeting participants where either the dominant or the marginalized discourse seemed to impact thought and shape social practice. Examples of clashing worldviews used as codes in my analysis include “tension between neighbors and developers” and “neighbors ask for slower pace/more information.”

In addition to what is said at CAC meetings, there are also absences and silences which can be as instructive as the words and phrases that are spoken aloud (Allan, Iverson, & Ropers-Huilman, 2010). While analyzing meeting transcripts, I asked of the data the following questions (Fairclough, 2003): How does the discourse make gentrification seem inevitable? How do CSU administration and the city represent desire as fact? How do they manage to represent their own preferences as foregone conclusions or present the results they hope to achieve as the way the world actually is?

Sometimes I found it challenging to code the transcripts or trace a pattern in the data. Individuals have multiple, overlapping, potentially conflicting identities, loyalties, and allegiances. According to Weedon (1997), there may be a range of incompatible discourses. I found excerpts that were challenging to code because they destabilized identity labels. For example, there were GES neighbors who supported CSU’s expansion into their neighborhoods and hoped for a mutually beneficial outcome, as well as others who were skeptical and distrustful of institutions. Several people’s sentiments shifted back and forth over time. There was no monolithic neighbor perspective. Wrestling with conflicts arising in the data was one of my leaping off points for analysis. Subtle meeting disruptions, as well as times when a CAC member worded the same proposal in markedly different ways from one meeting to another—these were flags that showed me where to look more closely. My project emanated from the places where there was tension among CAC members.

In “Aims of Critical Discourse Analysis” (1995), van Dijk provides the following ways to evaluate CDA work: CDA ought to focus on group relations of power and the ways these are reproduced or resisted through text and talk; CDA ought to trace discursively enacted strategies of dominance and resistance in social relationships; and CDA should uncover what is hidden or implicit, as well as focus on strategies of manipulation and the manufacture of consent. In addition, the CDA project should search for, catalog, and analyze discursive means of social influence, and identify “counter-power and counter-ideologies in practices of challenge and resistance” (van Dijk, 1995, p. 18). Finally, van Dijk states that CDA ought to involve analysis of how linguistic form and function correlate with each other, and how those correlations relate to specific social practices. These criteria guided me in choosing certain CAC meetings to really delve into. Figure 2 shows select meetings. Since the six-year data set was so extensive, the criteria above helped me decide how to drill down on certain moments and meetings.

Critical Discourse Analysis

CDA can be used to reflect critically on the social order, asking: what do the texts reveal about how social relations of power, domination, and exploitation are established and maintained (Fairclough, 2003)? Can power relations be altered? As Barbara Johnstone says, “discourse both reflects and creates human beings’ ‘worldviews’” (Johnstone, 2008, p. 33). Our speaking habits reveal the ways we imagine the natural and uncontestable world to be. Words call forth a system of beliefs about how the world works, how social life is organized, and why it came to be this way. The more we grow accustomed to hearing certain things, the more real and uncontestable they begin to seem. Johnstone says, “each time a particular choice is made, the possibility of making that choice is highlighted” (Johnstone, 2008, p. 46). It gains clout. This applies to the ways we speak about history, space, cities, institutions, education, social power, race, and each other: familiar ways of talking begin to make certain things invisible, as they recede into the blurry background of taken-for-granted common sense.

In Denver, those with concern about how quickly the city is changing can study the meetings where such changes are actually being negotiated. In this paper, I use CDA to search the meeting transcripts for “the legitimizing common sense which sustains relations of domination” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 207). I trace the evolution of the relationship between CSU and GES neighbors. Tension emerges in those relationships: what some consider gentrification, others see as an altruistic transformation of an area of the city that simply needs the gifts that a university can bring.

Findings

Speaking Power in the CAC Meetings

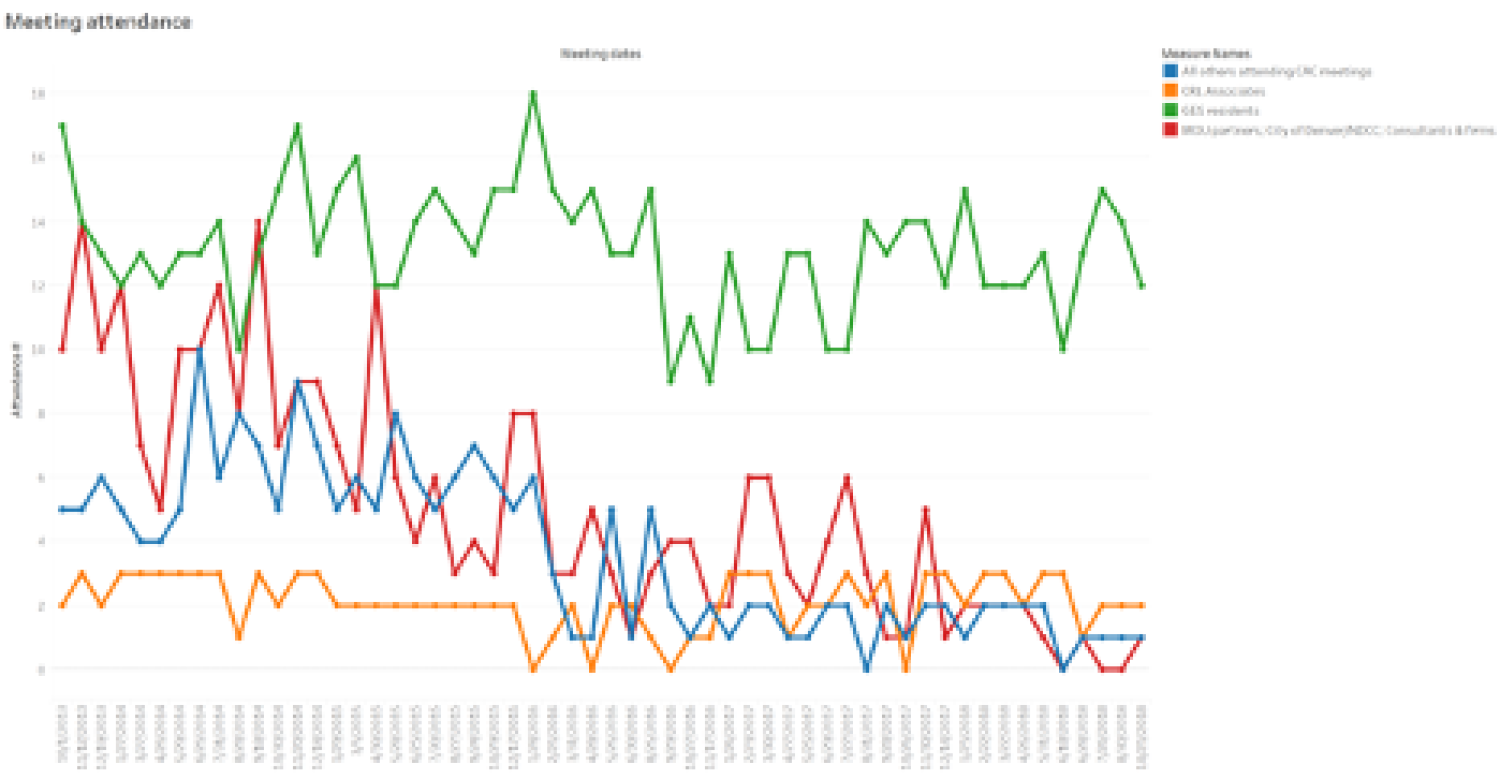

Table 1 (see Appendix) shows how many meetings took place over six years, bringing together CSU, the mayor’s office, developers, subcontractors, and CRL facilitators. Analyzing CAC meeting transcripts revealed how power moved through this administrative process. It is significant that in Meeting One, on October 1, 2013, 485 words were spoken by institutional partners before any GES neighbor uttered their first comment. That means the first 39% of the words uttered at Meeting One belonged to MOU partners—those institutions who signed a Memorandum of Understanding to redevelop North Denver together (see Figures 1 and 2; CSU is one of the MOU partners represented in red in Figure 1 and represented in green in Figure 2).

Only 22% of the words uttered at the entire meeting in October 2013 were from GES neighbors (274 words out of 1,245 total). Despite a written commitment from Councilwoman Judy H. Montero to create “strong communication and advocacy exchange between the neighborhoods” and the institutions in order to create “benefits to the community” (Master Plan, 2015, p. 3), MOU partners and the mayor’s office dominated Meeting One. What this did was convey to neighbors that social power would need to be wrestled away from normative institutions. The power and dominance of one class of CAC members was established through talk (van Dijk, 1995). Figures 1 and 2 show that this pattern continued in subsequent CAC meetings. While more GES residents consistently attended the monthly CAC meetings, the institutional leaders did more of the talking.

Figure 1

Meeting Attendance

Figure 2

Spoken Word Count at Select Meetings

Promises Made/Promises Broken

The dominance, inequality, and abuse of social power (van Dijk, 2003) did not go un-noticed by GES residents. A noteworthy moment of tension occurred when a neighbor attempted to push the CAC past a performance of inclusion and collaboration, into authentic deliberation and deep dialogue across difference. Vernon Hill’s letter (April 16, 2015, retrieved from the public archive) indicated that he wanted slow discussion and shared power between CSU, the NWC, and the families and neighbors living in GES. Neighbor Hill’s discourse of resistance and refusal attempted to interrupt institutional leaders from overpowering low-income communities of color. The letter said,

… In the history of Globeville Elyria and Swansea neighborhoods, a lot of promises have been made and not kept. We would like to see commitments to the neighborhood outlined and written down so that future generations of leaders … will continue to have a significant place at the table. … (Retrieved on 23 April 2019 from https://www.nwc-cac.com/documents.html).

The letter used resistant discourse, placing under scrutiny the relationship between the institutions and the community. “Promises … made and not kept” spoke to the history of economic neglect and infrastructural disempowerment faced by North Denver residents (Page and Ross, 2016; U.S. EPA, 2019). These words by Hill echoed John Zapien, another GES neighbor who spoke in a prior meeting of “poverty pimps that want to take advantage of people in this neighborhood” (CAC Meeting Transcripts, December 18, 2014, p. 1). Another neighbor named AE said she

sometimes feels like things are spun in the [NWC] newsletter. CRL is hired to facilitate [the monthly CAC meetings] but National Western Stock Show is their client and they often [sic] not supportive of the neighborhood. … We sincerely want to cooperate with NWC, and honor the stock show … We have opportunities for more mutuality between Globeville and the Center (CAC Meeting Transcripts, April 9, 2015, pp. 1 & 3).

No longer content to trust paid meeting facilitators to lead a frank discussion on how power moves in and through the CAC, the Hill letter was a discursive artifact that interrupted the status quo. Hill demanded that neighbors be the co-authors of a change process with institutional actors. The letter tried to stop the dampening, subduing, softening, and concealing of GES neighbor appeals. The institutions’ discursive practices and the desires from which they emanate were in tension with the residents’ discursive practices and desires. Neighbors were not content to merely participate on the CAC without power.

As I combed through the data, I catalogued moments when the neighbors’ counter-power and counter-ideologies were verbalized; they challenged and resisted the institutions (van Dijk, 1995). One of the GES residents attending an early CAC meeting, Tom Anthony said, “The Elyria neighborhood had a plan in 2006 …. We also had over 500 signatures to this plan …. We did a lot of this planning, and it appears that our concern is secondary to the National Western—not primary” (CAC Meeting Transcripts, December 19, 2013, p. 1). John Zapien said, “I’m concerned that this is just another page in the way this part of the city is treated” (CAC Meeting Transcripts, December 19, 2013, p. 2). AE picked up where her neighbors left off:

There is a real need for a transparent process; we need to know why certain things are happening. We haven’t had a conversation about our weight in this Advisory Committee, I’m feeling marginalized, and this doesn’t feel participatory ... This feels very “puppet mastery” and so how will we track accountability? We don’t want to be treated like we’re just another item on the checklist. … It’s important to understand how we live in these neighborhoods and connect with one another. (CAC Meeting Transcripts, December 19, 2013, p. 3).

This CAC meeting was marked by heightened tension over who would have power and control of North Denver’s redevelopment process.

CSU as Sunshine for GES

Fast-forwarding to a later CAC meeting, a CSU official illuminated a discourse about how inherently positive a university is. When she used a PowerPoint presentation that depicted new CSU facilities in bright greens and yellows against a backdrop of colorless GES neighborhoods on a map (CAC Meeting Transcripts, May 31, 2018), Jocelyn Hittle, CSU’s Director of Denver Program Development, chose to represent the new campus facilities as beacons for North Denver.

Lori D. Patton (2014), who also uses CDA to research higher education, suggests critically thinking about what listeners will take from a speech act, including both overt and subtle messages. What listeners in the CAC meeting in May 2018 might have taken from Hittle were these overt messages: new facilities will add value to our neighborhoods; the campus will serve our needs; the university is being responsive to our requests and ideas; CSU is collaborating with us. Even more subtle messages could also have been derived from Hittle’s framing of the CSU move to North Denver: because CSU is coming to GES, our neighborhoods are finally getting the attention and amenities we have been seeking for decades; higher education is good; CSU will give GES residents the opportunity to improve our life chances; the university is coming to help us.

Hittle chose phrases such as “supports the existing community” (CAC Meeting Transcripts, May 31, 2018, p. 3) that insinuated a beneficial relationship was forming between CSU and the neighborhoods. Her words made that so. No one in the CAC meeting held her accountable for justifying her claim or further explaining the contours of the eventual university-community relationship. CSU was not making promises about how access to the facilities by neighbors would be managed by the institution, nor were the neighbors in the meeting challenging Hittle to spell that out. Hittle’s characterization of the university-community relationship remained uncontested in the May 2018 CAC meeting. Through her words, Hittle discursively enacted a relationship among equals, as opposed to a relationship of dominance by the institution over neighbors.

Using a discourse of future-orientation and optimism, Hittle spoke about constructing together, and used words like “collaboratory,” “convening,” “solutions,” and “public meeting space” to evoke a bright shared future. She suggested that the surrounding neighborhoods would benefit from the new campus. She said, “These [buildings and facilities] will be accessible to the community, and educational for all” (CAC Meeting Notes, May 31, 2018, p. 4). Hittle’s discursive logic suggested that the presence of a university would bring distinction to the surrounding neighborhood. With CSU in their back yard, GES residents would have something of high value. Hittle also said, “CSU is introducing itself as a future neighbor to the Globeville, Elyria, and Swansea neighborhoods in an authentic way that respects, listens to, and supports the existing community” (CAC Meeting Notes, May 31, 2018, p. 5). Hittle focused listeners’ attention on benevolent acts by CSU, orienting the CAC toward the future. Hittle’s words promised GES neighbors and their dependents a brighter tomorrow. Hittle discursively enacted a relationship among equals, as opposed to a relationship of dominance by the institution over neighbors, by using the words “authentic,” “respects,” and “listens to.”

Elsewhere in the presentation by Hittle, architectural drawings of the planned campus reiterated this message, showing full-grown vegetation inside and outside. Hittle used these words and phrases to describe new campus facilities: “restored South Platte River” and “Site Re-generation.” Hittle’s discourse signaled that the university-community relationship should be interpreted in the following way: CSU will bring light and life to GES. Hers was a discourse of future-orientation and optimism; it promised a brighter future in a general sense. She used discursive strategies that focused attention on benevolent acts by the university.

Tour/Counter-Tour: A Deficit Orientation/An Implicit Strengths Orientation

Two competing conceptualizations of what should have transpired in the CAC meetings could be detected. These animated the dominant and resistant discourses. The dominant discourse by the institutions maintained that they were driving this change process. CSU, the NWC, two museums, and the Mayor’s office had the most unfettered access to professional expertise including consultants and subcontractors. They believed CSU and other institutional and municipal leaders should bring their plans to the CAC where neighbors could hear, ask questions about, and comment upon their plans. The resistant discourse was that institutions, residents, and neighbors should work together at every stage to collaboratively decide how to change North Denver. Both discourses, the dominant and resistant, were linked to the CAC’s confidence in the eventual redevelopment of the campus. One thing was for sure: this change was definitely coming.

Rewinding to an earlier meeting, a poignant moment from the data was a tour of the NWC that focused on dilapidation and crumbling infrastructure. We learned from National Western staff in Meeting One that “survival of the National Western requires year-round operations and bringing in [Colorado State University] helps with that” (CAC Meeting Minutes, October 1, 2013, p. 2). The first tour focused the CAC’s attention on the priority of making physical improvements to venues, stadiums, service roads in and out of the NWC, underpasses, and railroad tracks. Rather than conveying the CAC’s scope of work in words only, the tour punctuated the committee’s purpose for existing: to make decisions about upgrades to facilities. On the first tour, CAC members were shown a deficit perspective of North Denver: they saw infrastructure improvements that were sorely needed.

As the months went on, GES neighbors created a counter-tour that reframed the way space, cities, institutions in GES neighborhoods, and most importantly, people dwelling in North Denver were characterized and positioned in relation to each other. These two tours constituted the genetic makeup of the relationship between the institutions and the people who already lived in North Denver. At its core, the CAC meeting was a place of tension and conflict over the Citizens Advisory Committee’s very purpose: Did the CAC exist to plan physical improvements and enhance the earning capacity of the institutions, and were neighbors merely present in the room while plans were hatched by institutional leaders? Or was the committee’s purpose to be the democratic lever that GES residents could pull, in order to express to the institutions how the neighborhoods wished to change on their own terms? These were “instances of discourse [that] can be considered instances of social practice” (Fairclough, 1992, p. 207); they were efforts to steer the actions of the CAC according to differing worldviews. Higher education’s role in racially organizing cities could be seen in the tension between the tour and counter-tour. Differing discursive strategies worked to sustain racialized hierarchies in the city. Where institutional representatives saw and named dilapidation, GES neighbors highlighted use value (Lipsitz, 2011).

The neighbors on the CAC used the counter-tour to challenge the imaginary that had been articulated by CSU and the NWC. The counter-tour stepped outside the meeting, where GES neighbors shared a feeling of home, a multicultural celebration, and an honoring of the history of GES as priorities, ranking these as equal concerns alongside financial security and organizational growth for CSU and the NWC.

I found the theory from Lipsitz embedded in the sense-making process and the push-back by GES neighbors who planned the counter-tour. Neighbors argued back and insisted that while GES has real needs, they also have assets such as pride in their history and local organizations with resourceful and capable leaders. The counter-tour was intended as resistant discourse to influence the worldviews of CSU, an external institutional actor and a newcomer to GES. The counter-tour showed, despite heavy train traffic that freezes locals in place as they try to pass through their own neighborhoods, there are also parks in the community, scientific school-community partnerships with value, the Elyria-Swansea-Globeville Business Association, and many small, independently owned businesses catering to a Latinx clientele. The counter-tour asserted the value that GES neighborhoods already intrinsically had. GES residents on the CAC used the counter-tour to challenge the white spatial imaginary that was articulated by CSU and the other normative institutions.

Discussion

While the CAC offered GES neighbors a way to participate in the administrative processes to change North Denver, they participated without equal power. Institutional leaders merely performed inclusion. I use the word “performance” with intention: Sara Ahmed (2012) helps us conceive of the utterance of certain words as performances. Ahmed uses Austin’s (1975) term when she explains: “an utterance is performative when it does what it says: ‘the issuing of the utterance is the performing of an action’” (Austin, 1975, p. 6). Jocelyn Hittle utters the words, “CSU is introducing itself as a future neighbor to [GES] … in an authentic way that respects, listens to, and supports the existing community” (CAC Meeting, May 31, 2018, p. 4). This statement evokes Ahmed when she discusses how university leaders say they value diversity and hope that, just by saying so, the diversity work will be accomplished. Ahmed argues that these kinds of utterances fail to commit an institution to anti-racist action. Utterances alone are insufficient. Institutional actors must be held accountable to act, consistent with their utterances. Ahmed suggests that “‘texts’ are not ‘finished’ as forms of action, as what they ‘do’ depends on how they are ‘taken up’ …. To track what texts do, we need to follow them around” (Ahmed, 2012, p. 117). Likewise with discourse, I would argue.

After following institutions around in CAC meetings, I concluded that the administrative planning process by CSU and its allies in urban development were not sufficiently inclusive of GES neighbors. CSU and the NWC estranged neighbors from the administrative process of building the new campus. While the city’s administrative leaders were entitled to accumulate property and trusted to redevelop it, neighbors were not as successful at steering the decision-making that took place in CAC meetings. On the CAC, having neighbors present in the meeting room became a substitute for authentically including them. Even after Vernon Hill named this dynamic and demanded to become a co-author of the change process with institutional actors, and after the counter-tour made the resistant discourse vivid, neighbor inclusion was merely performed. CSU communicated in a way that painted higher education as a savior in a general sense, all the while, in this very specific, localized instantiation, CSU was engaged in a process of accumulation even as they used discursive strategies to make what they were doing sound like it would benefit everyone equally. The CAC represents a missed opportunity. CSU leaders could have taken advantage of six years of committee meetings to do deeper collaborative work with neighbors and community-based groups, dismantling spatial and racial oppression (Lipsitz, 2006, 2007, 2011) through the CAC meetings.

The administrative process used to grant valuable urban property to a PWI could easily have gone un-noticed. There was no one CAC meeting that deserved to make headlines in TheChronicle of Higher Education. Nonetheless, white privilege materialized in CAC meetings. In this study of a process of the racialization of higher education’s relationships with cities, I used moments of tension from meeting transcripts to show that racism is difficult to see, hear, and follow around, but it is still alive and well. In the most ordinary administrative spaces, in meeting rooms and on committees, “the ideologies of the powerful are central in the production and reinforcement of the status quo” (Bonilla-Silva, 2013, p. 74). Institutions have overpowered low-income neighborhoods of color in North Denver. The CSU expansion is an instance of a PWI lending itself to business interests and municipal leaders. Together, these institutional actors are removing people from land so that it can be used to fulfill their economic ambitions.

Conclusion

In my study, I sought to understand the racial context in which language was constructed. I sought to learn how social relationships were organized amongst CSU leaders, city staff, the NWC, and GES neighbors. I learned that the MOU partners dominated planning meetings, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. These findings have implications for higher education leaders, who ought to search for better ways to share power, deepen democracy, and forge symbiotic university-community partnerships. In addition, universities in the city ought to re-imagine how they serve and respond to the public. I recommend, moving forward, that CSU change their administrative practices to genuinely and deeply include GES neighbors. There are years of development and physical change to come. CSU still has the chance to act as an agent of racial and economic justice in North Denver.

This study also has implications for further inquiry, including more research into the complex topic of university expansion into cities. Since Darren P. Smith (2009) warns that concentrations of students can undermine the sustainability of neighborhoods and reconstitute urban areas, a long-term research project in North Denver could examine whether social exclusion, the marginalization of low-income families, the fragmentation of the community, deepening segregation, or a decrease in the availability of affordable housing (Smith, 2009) actually result from CSU’s presence. Another study could consider the advantages of the facilities, programs, and services that Jocelyn Hittle describes above, examining whether regeneration, increased spending power in the local economy, workforce readiness training, infrastructural improvements, access to the South Platte River, environmental education and remediation, art, and enhanced cultural vibrancy (CAC Meeting Minutes, 2013-2017) have truly come to GES, as neighbors requested. These priorities have guided the way that neighbors as a social group self-organized (Lipsitz, 2011) in the CAC meetings. Researchers could also measure the degree to which long-term residents have remained in the area, as well as study their quality of life, compared with pre-CSU expansion levels.

While it has been appropriate for the publicly available CAC meeting minutes to be the data set for this study, given my positionality as a white researcher who lives outside GES, in the future, another step that could be taken would be a Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR) project with residents who belong to the GES Coalition Organizing for Health and Housing Justice. CPAR is a form of community-based research that is accountable to those who have the most at stake. CPAR is about epistemic justice, counterhegemony, and decoloniality. CPAR assumes those who know the most about a community problem, such as displacement, are those who are living through it (Fine, 2008, 2018). This approach to research “helps researchers and the community integrate research with practice; enhance community involvement and control; and increase competence and sensitivity in working within diverse cultures” (Israel et al., 1998, p. 174). Through interviews collaboratively designed and data collaboratively collected, analyzed, and presented back to GES, this project could be taken beyond analysis to anti-racist action. Both the GES Coalition and Project VOYCE are organizations in North Denver that have already used community-based research to develop surveys and gather data on displacement. A future research collaboration with them could continue to grow new knowledge about the racialization of relationships between universities and cities.

In future studies, higher education researchers could further examine democratic processes at the municipal level: How does white privilege impact community advisory committees and their decision-making processes and outcomes? What would happen if those who serve on committees and advisory boards demand more power, using strategies like the counter-tour or Vernon Hill’s letter? What discursive strategies or conditions on committees and advisory boards could move more power into the hands of neighbors and families? In each of these thought experiments, the gaze is focused on white supremacy. More study of how to dismantle white supremacy in institutions and cities is urgently needed. Higher education leaders must keep focusing attention on whiteness in order to learn about administrative tendencies that reify white supremacy and re-entrench white power and perspectives. We must continue to investigate how to point to whiteness, make it visible, challenge and contest it, and choose deeper democratic and public processes that are anti-racist.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Allan, E. J., Iverson, S. V. D., & Ropers-Huilman, R. (2010). Reconstructing policy in higher education: Feminist poststructural perspectives. Routledge.

Austin, J. L. (1975). How to do things with words. Clarendon Press.

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing.

Bettie Cram Oral History. (2013, September 14). Denver Public Library Digital Collections.

Bettie Johnson Cram. Retrieved September 1, 2018, from http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15330coll23/id/12819

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2013). Racism without racists: Colorblind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Rowan & Littlefield Publisher.

CDOT. (2018a). Retrieved from https://www.codot.gov/projects/i70east/i-70-east-construction

CDOT. (2018b). Retrieved from https://www.codot.gov/about/CDOTHistory/50th-anniversary/interstate-70/construction-timeline.html

Chatterton, P. (2010). The student city: An ongoing story of neoliberalism, gentrification, and commodification. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(3), 509 - 514.

Colorado Tourism Office. (2019, August 8). Colorado tourism sets all-time visitor spending record in 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2020 from https://www.colorado.com/news/colorado-tourism-sets-all-time-visitor-spending-record-2018.

Cooper, J. G., Kotval-K, Z., Kotval, Z., & Mullin, J. (2014). University Community Partnerships. Humanities, 3(1), 88-101.

CRL. (2018). About. Retrieved from http://www.crlassociates.com/about/

CSU Center. (2018). CSU Center. Retrieved from https://nwc.colostate.edu/media/sites/78/2016/10/CSU-Center-1-pager.pdf

Delmendo, L. C. (February 12, 2018). U.S. house price rises continue to accelerate. Global Property Guide. Retrieved from https://www.globalpropertyguide.com/North-America/United-States/Price-History

Denver City Government. (2018). About. Retrieved from https://www.denvergov.org/content/denvergov/en/north-denver-cornerstone-collaborative/about-ndcc.html

Doeppers, D. F. (1967). The Globeville neighborhood in Denver. Geographical review, 57(4), 506 - 522.

DuBois, W. E. B. (1899). The Philadelphia Negro. University of Pennsylvania.

Etienne, H. F. (2012). Pushing back the gates: Neighborhood perspectives on university-driven revitalization in West Philadelphia. Temple University Press.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse. Routledge.

Ferman, B. (1996). Challenging the growth machine: Neighborhood politics in Chicago and Pittsburgh. University Press.

Ferman, B., Greenberg, M., Le, T., & McKay, S. (2021). The right to the city and to the university: Forging solidarity beyond the town/gown divide. The Assembly, 3(1), 10-34.

Fine, M. (1994). Working the hyphens: Reinventing self and other in qualitative research. In. N. K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 70-82). Sage Publications, Inc.

Fine, M. (2008). An epilogue of sorts. In J. Cammarota & M. Fine (Eds.), Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion (pp. 213-234), Routledge.

Fine, M. (2018). Just research in contentious times: Widening the methodological imagination. Teachers College Press.

Fine, M. E., Weis, L. E., Powell, L. C., & Wong, L. (1997). Off white: Readings on race, power, and society. Taylor & Francis/Routledge.

Fox, M. (2014). Town and gown: From conflict to cooperation. Municipal World Publishing.

Fullilove, M. T. (2004). Root shock: How tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America. New Village Press.

GES Coalition. (2017). Globeville Elyria Swansea People’s Survey: A Story of Displacement. Retrieved from https://www.gescoalition.com/download-housing-report

Gordon, S. P., Iverson, S. V., & Allan, E. J. (2010). Constructing the double bind: The discursive framing of gendered images of leadership in The Chronicle of Higher Education. In J. Storberg-Walker & P. Haber-Curran (Eds.), Theorizing women and leadership: New insights and contributions from multiple perspectives (pp. 81-105). Information Age Publishing.

Hargrove, M. D. (2009). Mapping the “Social Field of Whiteness”: White racism as habitus in the city. Transforming Anthropology, 17(2), 93-104.

Harris, C. (1995). Whiteness as property. In K. Crenshaw, N. Gotanda, G. Peller, & K. Thomas, (Eds.), Critical Race Theory: The key writings that formed the movement. The New York Press.

Haymes, S. N. (1995). Race, culture, and the city: A pedagogy for urban Black struggle. State University of New York Press.

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health.” Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173-202.

Johnstone, B. (2008). Discourse analysis, second edition. Blackwell Publishing.

Lipsitz, G. (2006). The possessive investment in whiteness: How white people profit from identity politics. Temple University Press.

Lipsitz, G. (2007). The racialization of space and the spatialization of race: Theorizing the hidden architecture of landscape. Landscape Journal, 26(1-07), 10-23.

Lipsitz, G. (2011). How racism takes place. Temple University Press.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press.

Mitter, S. (2018, April 18). Gentrify or die? Inside a university’s controversial plan for Baltimore. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/apr/18/gentrify-or-die-inside-a-universitys-controversial-plan-for-baltimore

Moore, T. (2013). Harlem and the Columbia Expansion. The Harlem Times. Retrieved from http://theharlemtimes.com/online-news/harlem-columbia-expansion

Nader, L. (1972). Up the anthropologist: Perspectives gained from studying up. U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Office of Education, Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED065375.pdf

National Western Center Master Plan (2015). NWC Master Plan. Retrieved from: https://nwc.colostate.edu/media/sites/78/2016/12/NWC_MPdoc_FINAL_web-3.3.15.pdf

NDCC (2017). “North Denver Cornerstone Collaborative,” The Six Portfolio Projects. Retrieved from https://www.denvergov.org/content/denvergov/en/north-denver-cornerstone-collaborative.html.html

O’Mara, M. (2012). Beyond town and gown: University economic engagement and the legacy of the urban crisis. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(2), 234-250.

Page, B., & Ross, E. (2017). Legacies of a contested campus: Urban renewal, community resistance, and the origins of gentrification in Denver. Urban Geography,38(9), 1293-1328.

Patel, L. (2015). Desiring diversity and backlash: White property rights in higher education. Urban Review (47), 657 - 675.

Patton, L. D. (2014). Preserving respectability or blatant disrespect? A critical discourse analysis of the Morehouse Appropriate Attire Policy and implications for intersectional approaches to examining campus policies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(6), 724-746.

Piton Foundation. (2018). Globeville Neighborhood Data. Retrieved from https://denvermetrodata.org/neighborhood/globeville

S&P Case-Shiller Denver Home Price Index, (April 24, 2018). Retrieved from https://us.spindices.com/indices/real-estate/sp-corelogic-case-shiller-denver-home-price-nsa-index

Salazar, P. (November 3, 2015). Press release: Denver voters say yes on 2C! Retrieved from http://www.nationalwestern.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/11.03-Yes-on-2C-Passes.pdf

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

Smith, D. P. (2009). ‘Student geographies’, urban restructuring, and the expansion of higher education. Environment and Planning A, 41(8), 1795 - 1804.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Smith, D. P., & Holt, L. (2007). Studentification and “apprentice” gentrifiers within Britain's provincial towns and cities: Extending the meaning of gentrification. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space,39, 142-161.

Source Newsletter. (November 3, 2017). National Western Center Breaks Ground. Retrieved from https://source.colostate.edu/national-western-center-breaks-ground-denver/

Stein, S. (2016). Universities, slavery and the un-thought of anti-Blackness. Cultural Dynamics, 28(2) 169 - 187.

Stein, S. (2017). A colonial history of the higher education present: Rethinking land-grant institutions through processes of accumulation and relations of conquest, Critical Studies in Education, 61:2, 212-228.

Tracey, C. (2016, July 14) “White privilege and gentrification in Denver, America’s favourite city,” The Guardian (UK). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/jul/14/white-privilege-gentrification-denver-america-favourite-city

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2019). Vasquez Boulevard and I-70 Retrieved from https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/cursites/csitinfo.cfm?id=0801646

van Dijk, T. A. (2003). Introduction: What is critical discourse analysis? In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, & H.E. Hamilton (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 352-371). Blackwell Publishers Incorporated.

Weedon, C. (1997). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory, second edition. Blackwell Publishers Incorporated.

WhatsPOPPYN. (Producer). (November 9, 2017). “Temple University and displacement in North Philadelphia.” WhatsPOPPYN. Podcast retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8DhXI2fWzV4

White, G. B. (2016). “The downside of Durham’s rebirth.” The Atlantic Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/business/

archive/2016/03/the-downside-of-durhams-rebirth/476277/

Appendix

Figure 3

Business Slated for Demolition

Note: Street View of 1632 E. 47th Ave. in Denver, CO, Google Maps, 17 March 2019.

Figure 4

Home Slated for Demolition

Note: Street View of 1655 E. 47th Ave. in Denver, CO, Google Maps, 17 March 2019.

Figure 5

Home Slated for Demolition

Note: Street View of 4657 Baldwin Ct. in Denver, CO, Google Maps, 17 March 2019.

Figure 6

Homes in Front of the Denver Coliseum

Note: Street View of 4681 Baldwin Ct. in Denver, CO, Google Maps, 17 March 2019.

Figure 7

Home Already Demolished

Note: Street View of 4660 Baldwin Ct. in Denver, CO, Google Maps, 17 March 2019.

Figure 8

Business Already Demolished

Note: Street View of 4712 Baldwin Ct. in Denver, CO, Google Maps, 17 March 2019.

Figure 9

Homes Already Demolished

Note: Street View of 4667 Baldwin Ct. in Denver, CO, Google Maps, 17 March 2019.

Table 1

CAC Meeting Minutes Analyzed in this Study

Date Topics

9-11-18 Placemaking, Citizen Comments

8-30-18 Community Benefits Agreement, Choosing NWC Board CEO

8-23-18 Placemaking

7-26-18 Placemaking, Youth Water Expo

6-26-18 Construction Update

6-18-18 Cultural Plan

5-31-18 Demolition Plan, Placemaking

4-26-18 Campus Energy Options

4-3-18 Stormwater Study

3-22-18 Campus Placemaking

2-22-18 Parking and Transportation

1-25-18 RTD Station Naming, Construction Alerts

12-14-17 Placemaking Survey

11-30-17 CSU Community Outreach

10-26-17 Parking and Transportation Demand Management

10-12-17 Citizen Comments

9-28-17 Branding Presentation, Citizen Comments

9-7-17 Framework Agreement, Citizen Comments

8-31-17 Citizen Comments

8-23-17 Citizen Comments

8-10-17 Framework Agreement, Citizen Comments

7-27-17 Campus Placemaking Study

6-29-17 Governance and Terms Briefing, Branding, Placemaking

5-25-17 Placemaking Study by MIG, Inc.

4-27-17 Placemaking

3-30-17 Parking and Transportation Demand Management

2-23-17 NextGen Agribusiness Economic Study, New NDCC Staff

1-26-17 CSU Staff Report, Citizen Comments

12-15-16 Meeting Canceled

11-17-16 Denver General Obligation Bond Presentation

10-27-17 Washington Street Study

9-29-16 47th Avenue Bike Lane Presentation

8-25-16 Citizen Comments

7-28-16 Meeting Canceled

6-30-16 CSU Water Resources Center Presentation

5-26-16 Draft Economic Study

4-28-16 Memorandum of Understanding Between Collaborators

3-31-16 Draft CAC Meeting Guidelines and Membership Criteria

2-25-16 CSU Agriculture Innovation Study, Regeneration Presentation

1-28-16 Yes on 2C Presentation, Parking and Transportation Demand Management

12-17-15 Work Session, Citizen Comments

10-29-15 Citizen Comments

9-24-15 Citizen Comments

8-27-15 Riot Fest Presentation, Citizen Comments

7-30-15 Historic Resources Work Plan

6-25-15 Call for Self-Nominations, Citizen Comments

5-28-15 GES Implementation Committee, Neighborhood Activation Plan

4-30-15 Vernon Hill Letter, Brighton Boulevard Presentation, Citizen Comments

4-16-15 Zoning

4-9-15 Zoning

3-25-15 Citizen Comments

3-19-15 Zoning

3-12-15 Zoning

3-5-15 Zoning

1-29-15 RTA Letter

1-13-15 Preamble Draft Presentation

1-6-15 Citizen Comments

12-18-14 Master Plan Presentation, Citizen Comments

11-20-14 Master Plan Tentative Timeline, Citizen Comments

10-30-14 Project Summary, Citizen Comments

9-18-14 Citizen Comments

8-28-14 Master Plan Presentation, Citizen Comments

7-31-14 Planning Presentation

6-26-14 Vision and Values Statements, North Denver Cornerstone Collaborative (NDCC) Presentation

5-29-14 Roundup Retreat Presentation

4-24-14 Citizen Comments

3-27-14 Feasibility Study, Vision Discussion

2-27-14 Historical Assessment, Master Plan Discussion

1-27-14 Neighborhood Tour

12-19-13 Master Plan

11-12-13 Citizen Comments

10-1-13 Welcome to CAC, Citizen Comments