Social media shakes up disaster communications

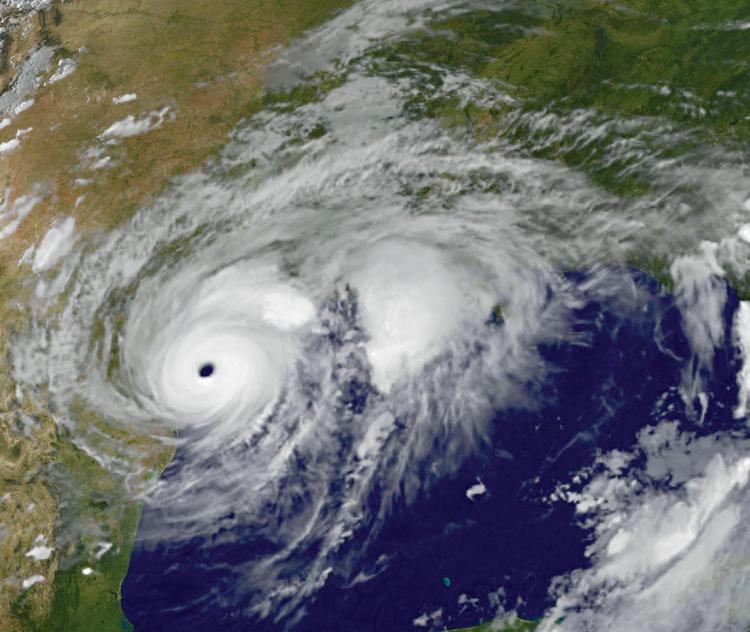

As Hurricane Harvey bore down on Houston in August 2017, the Twitterverse lit up with satellite images warning of danger and 140-character exchanges between worried residents.

For those in Harvey’s path, the tweets provided information, comfort and sometimes confusion. For Leysia Palen, they provided data points.

“I am interested in the nature of human cooperation and coordination. How does it happen? How does it fail? And what can we do to make it better?” said Palen, founding chair of the information science department and pioneer in the burgeoning field of “crisis informatics.” “There is no more extreme environment to study this in than a natural disaster, and social media makes it possible on a mass scale.”

Since 2006, when Palen was awarded a $600,000 National Science Foundation CAREER Grant that helped her launch the field, she’s attracted 6 million dollars to study how digital technology shapes disaster response.

She and her students were embedded among emergency personnel during the 2013 Colorado floods, collected tweets in real-time during the 2015 Nepal earthquake, and evaluated how digital maps helped and hindered aid workers after the 2010 Haiti quake. Now they’re scouring tweets from the 2017 hurricane season for a project designed to make forecast images easier for those in harm’s way to understand.

“Crisis informatics enables us to use technological skills to solve real-world problems,” said Melissa Bica, a PhD candidate who was drawn to CU Boulder by Palen’s research.

In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit, smartphones weren’t so common or “smart,” and Twitter didn’t exist. Today, digital technology gives ordinary citizens a voice once largely reserved for government officials or media: describing the scene, soliciting aid and drawing sympathetic gazes from afar.

But with this shift has also come misinformation.

“People have this expectation of journalist accuracy, that the images of disaster they see on social media represent what is happening in real time on the ground,” Bica said. “That is not always the case.”

For instance, one study of 13 million tweets exchanged during the Nepal earthquake found that Twitter users (especially outside of Nepal) sometimes appropriated images from elsewhere—a 2007 photo of young siblings in Vietnam, monks praying in 2010 in Thailand— saying they were from Nepal.

While such photos may be posted without ill intent, information intended for purposes other than eyewitness accuracy can cause problems for aide or rescue organizations that use social media to inform decisions. Even posts from official sources can be misinterpreted.

For the hurricane study, a collaboration with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Palen and her students collected 10 million tweets from Harvey, Irma, Maria and Nate, zeroing in on those containing risk forecast images such as satellite imagery or graphics showing the “cone of uncertainty” where the storm may hit next.

“We are finding that, often, people don’t understand what they see,” said James Dykes, a PhD student in information science. Eventually, he hopes, the data and feedback gathered through the study can help forecasting agencies improve their images.

With six of her PhD graduates having started crisis informatics research around the country, and emergency response officials using the research to inform their work, the field Palen founded has almost certainly saved lives.

As she put it: “Being part of a small, innovative department at a research university can lead to pretty amazing things.”

Principal investigator

Leysia Palen

Funding

National Science Foundation

Collaboration + support

College of Media, Communication, and Information; Information Science; National Center for Atmospheric Research