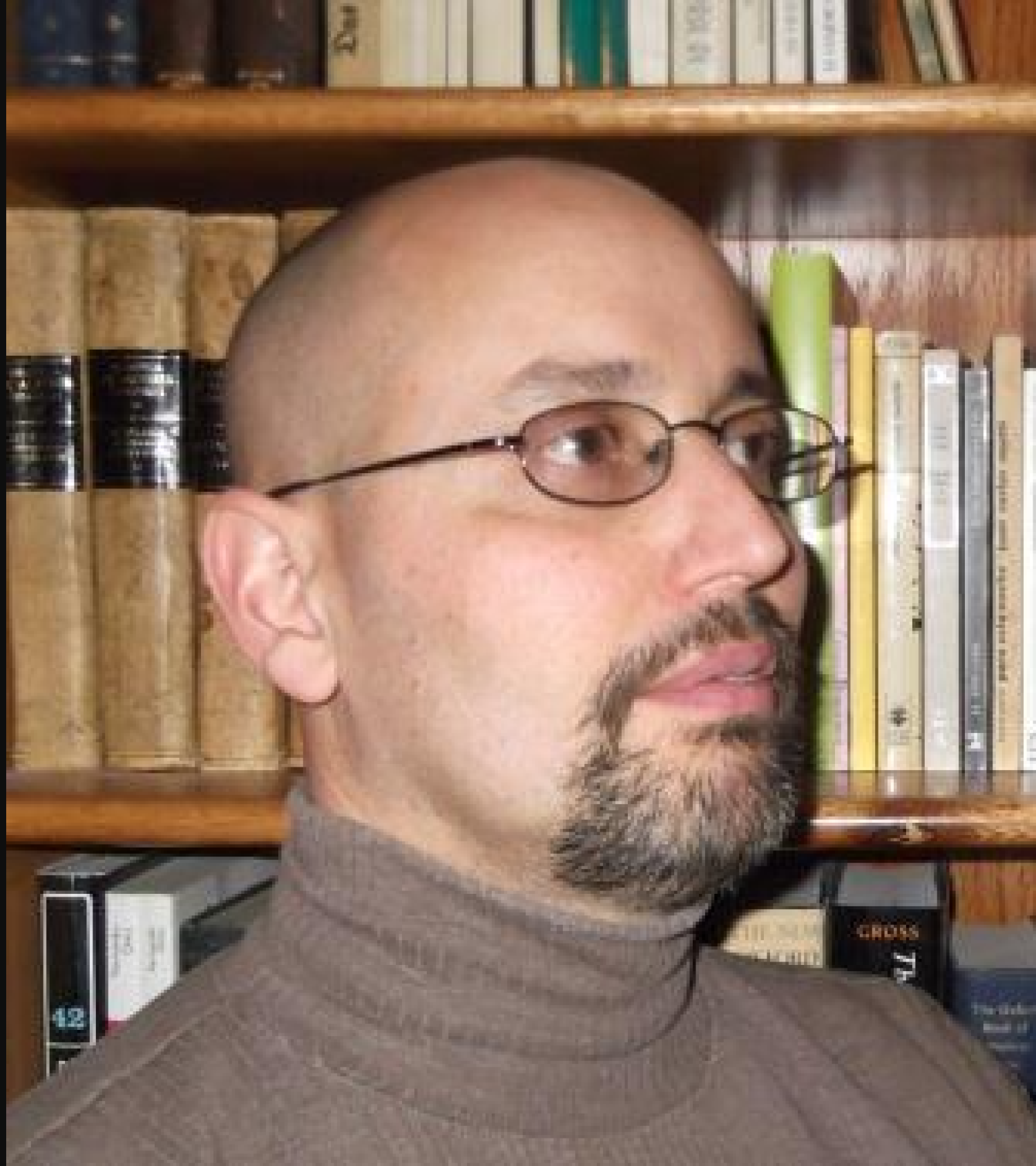

Juan Pablo Dabove

- Professor

- SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE

Juan Pablo's family will hold a memorial for him, which his students and colleagues are invited to attend. It will be Friday February 28th at 3:30pm at the Koenig Alumni Center. Those unable to attend in person are invited to join us on Zoom.

Juan Pablo Dabove (1969-2025)

Research Interests:

Postcolonial Latin American Literature and Culture. Bandit Narratives. Gothic Literature.

Overview:

Considered one “of the most significant commentators of Hispanic narrative” by the Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos, Juan Pablo Dabove’s research focused on 19th- and 20th-century Latin American literatures, cultures, and history. His book, Nightmares of the Lettered City: Banditry and Literature in Latin America, 1816–1929 (Pittsburgh, 2007) was the winner of the 2010 Kayden Award and was met with critical acclaim for its insightful and comprehensive analysis of the portrayal of banditry in Latin American literature. Drawing on the concept of the “lettered city,” coined by Ángel Rama, Dabove explored how bandits were constructed in literature as symbols of resistance, rebellion, or disorder, depending on their alignment with or opposition to emerging state powers. This book was followed in 2017 by Bandit Narratives in Latin America: From Villa to Chávez, also published by Pittsburgh. In this sequel, Dabove extended his exploration of banditry into the 20th and 21st centuries, focusing on how the figure of the bandit has evolved in literature, film, and political discourse. The book examines iconic figures like Pancho Villa and Hugo Chávez, analyzing their representation as both heroes and outlaws. Dabove considered how bandits challenge traditional notions of power, justice, and social order, emphasizing their symbolic role in critiques of state authority and capitalism. Like its predecesor, Bandit Narratives was critically acclaimed, particularly for the way in which illuminated the intersection of history, nation-building, literary, cultural, and social traditions in Latin America, engaging in a broader discussion about the nature of language, literature, and the role of intellectuals in the region.

In the last few years, Dabove became interested in Gothic literature, probing the relationship between Gothic modes of representation and the crisis of liberalism in Latin America. By exploring how the Gothic aesthetics has been employed by Latin American writers, and its role in expressing social anxieties and historical traumas, Dabove’s research shed light on the Gothic’s role in articulating Latin America’s complex histories and identities. At the moment of his passing, Professor Dabove was working on a book project titled, The Gothic Moment in Argentine Culture.

Professor Dabove lectured nationally and internationally, being invited to deliver keynote addresses or as guest speaker at several conferences and universities in Latin America, Europe, and the United States. He contributed several entries for various dictionaries and encyclopedias of Latin American literature and culture, as well as several book chapters and articles for edited volumes, ranging in topic from canonical authors, such as José Fernández Lizardi or Jorge Luis Borges, to lesser-known writers. Dabove was also very active in the Latin American Studies Association, the largest association of scholars studying the region.

Personal Remembrances:

Smart. Funny. Driven. Juan Pablo was all of these things and more. He convinced me to pursue a master's degree in Spanish literature at CU-Boulder. If it hadn't been for his encouragement, I never would have applied. His unique perspective and insights opened up a whole new world for me and gave me a greater appreciation of Latin American literature.

He left us too soon and will be dearly missed. I take solace in my fond memories of him and the works he left behind.

-Nikki

Juan Pablo and I were not close friends. More often than not we were on opposite sides of issues discussed at a Departmental meeting, or in an exchange of committee emails, or even during an M.A. or PhD comprehensive exam. Our explicit or subconscious agendas were at times mutually exclusive, and that meant frequent clashes. That frequency, though, that amount of interaction, that abundance of point/counterpoint engagement built, over the years, a measure of mutual respect as solid as personal friendship, because one thing that we had in common was the worship of sincerity, the unmovable basement of honesty, and the impulse to shake a worthy adversary’s hand.

When we were hiring for his position, I asked around, among my own Pittsburgh-related friends (he was later surprised to find out that I had a few), and the answer I got (more confidential and perhaps more sincere than rec letters) was that Juan Pablo Dabove was a superb candidate. It was a time in our Department in which we were building a strong Latin-American program which included the recruiting of the many top-notch Latin American graduate students that now are our colleagues in Academia not only in the US, but also in Latin American countries. Juan Pablo, a true workaholic, was vital in the spectacular lift-off of our Latin American section.

We couldn’t be more different. From the way our stuff is written to the way we kept our offices. His was in perfect order (compulsive at times) while mine was, as you all know, a mess, “una leonera.” It was in his office that I saw him for the last time, about a year ago, when I went to campus to attend a lecture by John Gardner, whose PhD dissertation I directed years ago. Juan Pablo was not attending the lecture—he had class—but he was in his office. I knocked and entered, and he received me with a big smile of both surprise and joy, and a big hug. He was happy to see me, and so was I.

Before this encounter, we had another one in which we managed to express to one another our friendship, our great respect for one another, and our vast reservoir of values and ideas in common. It was at his house. I was retiring—it was at the end of the covid pandemic—and the Department was trying to organize something in my honor, which eventually happened, but not before Juan Pablo organized something at his home, with a few colleagues invited, in which I felt deeply moved, and surrounded by the best company. It was not an institutional act. It was the personal initiative of a not-close friend who held me in high esteem, just as I held him. “Thanks for all these years: we’ll miss you”—he was saying to me. Thanks for all these years, Juan Pablo: we’ll miss you—is what I now want to say to him.

-Julio Baena

Juan Pablo was a respected scholar whose work played a key role in making the Department of Spanish and Portuguese one of the top graduate programs (as recognized by the National Research Council). His research had a strong impact on the academic community. At literary conferences, mentioning CU Boulder instantly brought to mind the name "Juan Pablo Dabove." We will miss the gaucho!

-Tania Martuscelli

When I first joined CU Boulder and I didn’t know I would end up being part of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese (I was in the Humanities Program for one semester), Juan Pablo sent me a welcome to CU email. In addition to the formalities about work and collaboration of a welcome email, Juan Pablo explained the context of why he was “tuteándome" right away noting that using “usted” in Argentina is currently a sign of deliberate distance, rather than a show of respect. Immediately, I knew I would have a respectful and careful colleague on campus. When, a few months later, I joined the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, this became even truer.

-Élika Ortega

Juan Pablo joined the department in an important moment of transition and hit the ground running by making valuable contributions across all areas of crucial departmental need: teaching, research, service. During these early years, we both had our offices next to each other in the basement. He used to listen to loud music when he was preparing his seminars. The energy coming through the wall was contagious, and I remember him telling me with joy “This is what I always wanted to do.”

-Mary K. Long