Engineers, students played key role in hunt for alien worlds

View of the Kepler Mission Operations Center at LASP (top); former CU Boulder graduate students Sierra Flynn and Evan Graser inspect information streaming down from the Kepler spacecraft (bottom). (Credits: Glenn Asakawa/CU Boulder)

Has NASA’s famed planet-hunting spacecraft met its end? Not so fast, say CU Boulder researchers.

Last week, NASA announced that the Kepler Space Telescope, which searched for planets orbiting stars far away from Earth, had run out of fuel and would finish its nine-year mission. In response, many news outlets reported that Kepler was dead

But Lee Reedy, flight director for Kepler at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), said that the mission’s legacy is far from over. To date, Kepler has found a confirmed 2,662 planets beyond our solar system. “And while it will no longer collect data, Kepler will live for a dozen years or more because there are going to be people mining the data it has collected for at least that long,” he said.

It’s a legacy that LASP has played an important, but mostly behind-the-scenes, role in. The institution has managed Kepler’s operations since its launch in 2009, overseeing the spacecraft’s day-to-day activities and responding to emergencies in space. Those operations were undertaken by professionals like Reedy, who led the Kepler team, and by undergraduate students who each completed 500 hours of training.

Their efforts—including late-night shifts at an operations center on campus—paid off, helping scientists reevaluate what they think exists in the universe, said LASP’s Darren Osborne.

“We really didn’t know before Kepler came along how prevalent planets were in the universe,” said Osborne, flight director for multiple NASA missions, including Kepler. “Now we know there are more planets than there are stars, and there are more stars in the universe than there are grains of sand in all of the beaches in the world.”

New life

Kepler had come close to finishing its mission before. In May 2013, the spacecraft signaled that it had lost two of its four reaction wheels, the motors that allowed the spacecraft to swivel in space. Kepler seemed dead in the water.

Engineers at Ball Aerospace, which built the spacecraft, came up with a strategy for saving the spacecraft with input from LASP’s Kepler team. They devised a workaround that would allow them to continue pointing Kepler at far-away stars while ensuring that the telescope could send data back to Earth.

“This is one of the very few space programs where you completely redesign the mission in orbit,” Reedy said.

While Kepler’s new lease on life highlighted LASP’s involvement in the mission, Reedy’s group did a lot more than manage crises. The team was in regular contact with the spacecraft, sending it commands, checking to make sure that it was working properly and downloading its observations. Over Kepler's lifetime, dozens of students sent more than 732,000 commands to the spacecraft, conducted analyses of its subsystems and trained other student command controllers.

LASP currently conducts similar operations for two other NASA missions: Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesophere (AIM) and the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE). The NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, leads Kepler’s science team. LASP’s efforts paved the way for a wealth of scientific findings. Among other coups, Kepler confirmed the orbits of seven planets about the size of Earth orbiting a star called TRAPPIST-1. It also located a huge pile of rubble circling “Tabby’s Star,” which scientists believe is made up of the remnants of a planet that broke up in orbit.

The telescope didn’t limit itself to planets, either: “We were looking at monster black holes,” Reedy said. “And we were looking at hot plasma jets and the beehive cluster,” a jumble of stars about 600 light years from Earth.

“One of the great things about this mission is that it captured the imagination of the world,” he said.

[video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yd18oZqdmdo&feature=youtu.be]

The hunt continues

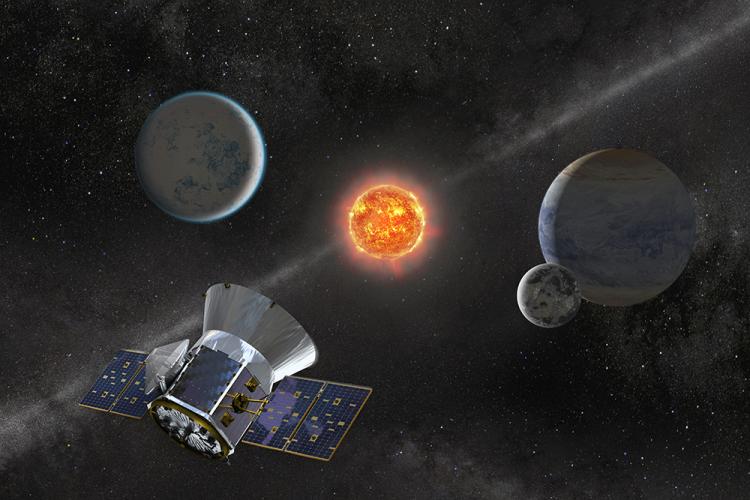

Artist's concept of the TESS spacecraft with exoplanets. (Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)

His student employees weren’t immune to that excitement. Reidar Larsen trained to work on Kepler and the other spacecraft that LASP operates in the summer between his freshman and sophomore years as a student studying aerospace engineering.

He remembers coming across articles about Kepler’s new discoveries. “I would say, ‘that’s the spacecraft that I operate. I probably helped to bring the data down for that discovery,’” said Larsen, now a graduate student at LASP.

The LASP team will soon send the official "goodbye commands" to Kepler, which will shut down the spacecraft's computer systems for good. The telescope is currently orbiting the sun about 106 million miles from Earth.

“I think for a lot of us, it’s bittersweet,” said Trevor Weschler, an undergraduate student studying aerospace engineering who also worked on Kepler. “It was cool to feel like we were taking part in something bigger.”

But scientists also aren’t done looking for planets, said Zachory Berta-Thompson, an assistant professor in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences at CU Boulder. He has studied exoplanets using Kepler data and is a collaborator on NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). That mission launched in 2018 and will take up Kepler’s banner of seeking out new alien worlds.

“Kepler stared at only a tiny fraction of the sky,” Berta-Thompson said. “Now that we know planets are common, TESS is taking the next step, searching the entire sky for the closest examples of every kind of planet that’s out there.”