Photo: Ball Brothers Orbiting Solar Observatory with employees and rocket parts, 1961-64. Courtesy of Boulder Historical Society.

CU Boulder and Ball Aerospace have been collaborating for decades to solve mysteries of the universe. That partnership was also the university’s first commercial spin-off and it greased the gears of an entrepreneurial engine that continues to power innovation within the university and far beyond.

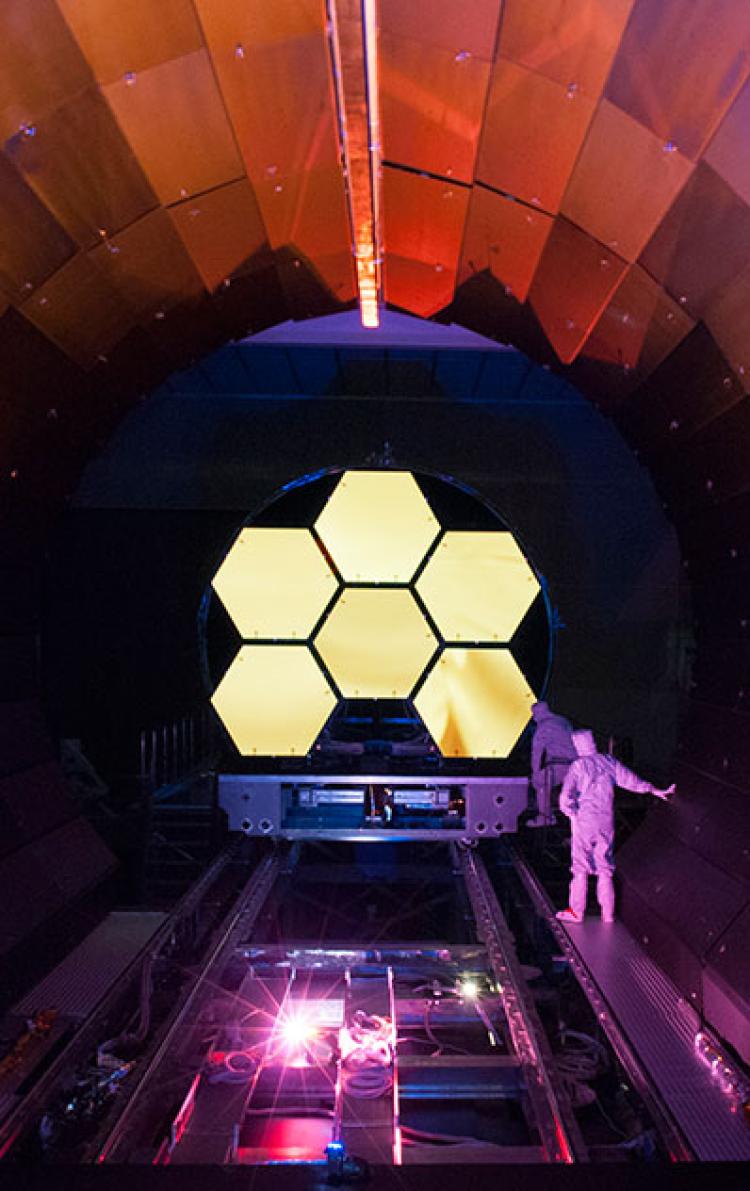

Photo: Ball designed and built the advanced optical technology and lightweight mirror system that enables the James Webb Telescope to look 13.5 billion years back in time. Courtesy of Ball.

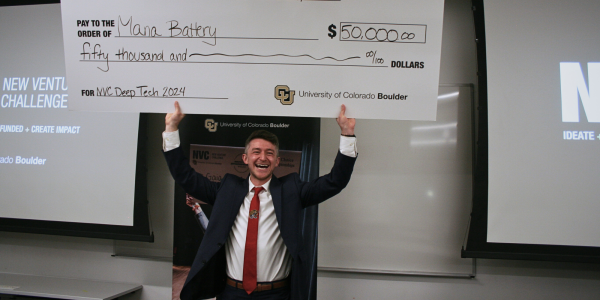

When NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope launched in late 2021 the work for some scientists was just beginning. As the observatory reached its deep-space destination, its 18 hexagonal mirrors had to be deployed and aligned over several months by engineers working round-the-clock.

One of those scientists was Katie Melbourne who, at the time, was a part-time CU student (Aerospace) and a scientist at Colorado-based Ball Aerospace. The company designed and built the advanced optical technology and lightweight mirror system that will allow Webb to look 13.5 billion years back in time, adding to Earthlings’ knowledge of the evolution and properties of distant galaxies. “I got really lucky because I was actually on shift when they stepped out all the mirrors from their stowed position and the mirrors were fully deployed,” she said.

Melbourne’s team focused on properly positioning each of the mirrors, a task requiring intense patience and precision. “We were working on aligning the mirrors so that Webb can actually take science data. And so that’s a four-to-six month, 24/7 process,” she said. That painstaking work paid off as the telescope captured its first remarkable images in mid-2022.

“I grew up with Webb being this future thing and thinking maybe I’ll do astronomy and use data from it someday. Working on it was a dream come true,” said Melbourne, who is now pursuing a PhD full-time in astrodynamics and satellite navigation systems in the department of aerospace engineering sciences at CU Boulder.

Melbourne’s work and studies are emblematic of the ongoing, and often historic, collaborations between Ball Aerospace and CU Boulder over the past 75 years. Since the company launched decades ago, over 500 CU alumni have joined Ball Aerospace and the company continues to sponsor research, scholarships and student projects. The partnership endures in another influential way: Ball paved the way for CU researchers to turn their discoveries into innovations with real-world impact across fields as diverse as healthcare, quantum systems and sustainability.

Setting their sights on the sun

Photo: In 1953, UAL succeeded in launching the first rocket to observe the Sun's ultraviolet radiation above Earth’s atmosphere leading to the spinoff of Ball Aerospace in 1956. Courtesy of LASP.

In 1948, a decade before NASA was formed, the U.S. Air Force contracted with professors and graduate students in CU Boulder’s physics department to run a first-of-its-kind suborbital program to study the sun. With their “Rocket Project,” the CU scientists set their sights on the still-mysterious sun to measure deep ultraviolet radiation emanating from it and, with that data, improve communications and expand understanding of astrophysics.

It was no small feat to invent and affix precise and durable instruments that could take measurements from the back of a wobbly rocket in the still-unknown vacuum of space—but physics department chair William Pietenpol was keen to try.

For years he and his team toiled in the basement of the Hale Science Building and, as their operation grew, in tents on the lawn outside. Ultimately, they created the first “biaxial pointing control” system, built to ride on retrofitted World War II munitions. Those “sounding rockets,” or research rockets, carried scientific instruments within their otherwise ordinary-looking nosecones and, if successful, would collect data during short, suborbital flights.

After four prior attempts, the sun-seeking Aerobee-Hi rocket was successfully launched in the early 1950s from the White Sands Proving Ground. The sounding rocket climbed beyond the ozone layer and into Earth’s upper atmosphere while keeping its payloads sun-facing to take spectrographic measurements of the sun.

“That mission was driven by the scientists, the physicists here on campus, saying, ‘Hey, we really want to do these cool measurements of the sun outside the atmosphere, and rising to the challenge of, ‘How do we do that’?” said Smead Director of the Ann and H.J. Smead Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences Chris Muldrow. “That was the beginning of the development of the science of how to use aerospace platforms, technologies, aircraft, spacecraft, to do really cool science.”

Pietenpol’s team went on to start the Upper Air Laboratory (UAL). The UAL was renamed the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) in 1963—and it remains one of the nation’s top university-based space research institutes. Rocketry is still fundamental to LASP, CU’s oldest and highest-budget research institute. It is the only academic research institute in the world to have sent scientific instruments to every planet in Earth’s solar system—plus the sun and many moons.

They didn’t know it then, but those early CU space researchers were laying the foundation for two important and enduring entities. Those include LASP, an institute that remains at the cutting edge of space science and Ball Aerospace, a company that would later be a key player in many of the nation’s pioneering space missions.

From glass jars to distant stars

Photo: A rocket pointing control unit being checked by four Ball Brothers staff, 1965. Courtesy of Boulder Historical Society.

While the CU Boulder physicists were working around the clock on campus, Edmund Ball—the president of a well-known glass jar manufacturer in Indiana—was looking to fuel a new research and development division to diversify Ball’s industry base. Five Ball siblings (including Edmund’s father) had founded Ball Brothers Glass Manufacturing Company in 1880, making tin cans, then hundreds of millions of now-iconic glass jars, eventually becoming a household name.

Why was the leading manufacturer of Mason jars interested in Earth’s upper atmosphere? At the time, the “space race” was heating up (the former Soviet Union launched Sputnik, Earth’s first satellite, in 1957) and Edmund Ball was eager to be on that new frontier. The “space field” was, he said, “the beginning of the biggest scientific effort in our nation’s history.”

The CU Boulder scientists’ huge achievement with the sounding rocket had made national news and, when Ball was visiting Boulder on different business, he met David Stacey, a CU physicist who had taken the lead on several important aspects of the Rocket Project.

In late 1956, in a climate of post-war optimism and exciting technological innovation, Ball asked Stacey and several other Rocket Project key players to join forces with him to form CU Boulder’s first spin-out and Boulder’s first high-tech company—Ball Brothers Research Corporation (now Ball Aerospace). They moved into a new building on Arapahoe Road in Boulder and, crucially, brought with them their pointing control system designs

Despite lucrative contracts in Ball Aerospace’s early days, innovation was expensive and the nascent company’s profitability faltered. In 1958, they brought in Ruel “Merc” Mercure to help write Ball’s next chapter. Mercure had gotten his PhD in physics at CU Boulder and had designed the instrument that photographed the sun while atop the Aerobee rocket.

Years later, Mercure told the Denver Post what it was like in those early days of launching rockets and, ultimately, the space business. “It was great, great, great, great fun,” he said. “The word today is passion—that’s probably a good way to describe all of us that were involved at the time…Nobody had done these things before. Aerospace was very, very new.”

Mercure wrote in his CU dissertation that space was an “area of scientific endeavor in which the smallest success brings with it a great personal sense of achievement and pleasure.” Nevertheless, it was giant leaps that lay ahead. “Merc built a reliable and reusable satellite platform at a time when satellites were becoming an important thing—and Ball was the SpaceX of its generation,” said Kyle Lefkoff, founder and general partner of Boulder Ventures who later worked with Mercure.

As one of the founding engineers of UAL/LASP and later the president of Ball’s research group, Mercure helped put CU Boulder, Ball and the city of Boulder at the center of aerospace science and engineering. He also encouraged innovation and investment to come together in new and meaningful ways. “Merc was the founder of Boulder’s entrepreneurial ecosystem that is a fundamental driver of economic benefit for the whole country,” said Lefkoff. “He was motivated by venture creation, entrepreneurs, the quality of science–the importance of taking ideas from the laboratory into products.”

Removing barriers to innovation

Photo: R.C. “Merc” Mercure Jr., a CU Boulder alumnus and entrepreneur who helped launch Boulder into the pantheon of aerospace science and engineering, died on Feb. 10, 2022, in Boulder. He was 90.

Mercure ultimately moved on from Ball to found and invest in several other ventures, and to impact—on an even larger scale—how university labs can be major economic drivers. He returned to CU Boulder in 1988 to serve as (among other positions) director of CU’s new Technology Transfer Office.

At the time, the U.S. government had recently begun to grant ownership of inventions back to the universities that had created them with federal funding (which enabled the field of “tech transfer”) to better connect academic innovation with the mainstream economy—boosting economic development in the process. Dubbed the Bayh-Dole Act, the legislation allowed universities to license federally funded inventions to private industry, which CU soon did.

Lefkoff worked on tech transfer with Mercure from 1986 to 1999. “Merc and I helped CU design the tech transfer program based on what was best practice among the best universities at the time,” he said. “We let the professors know that when you invent something at CU, if you have the human capital to make that happen, there’s no institutional barrier. That was an epiphany for many of them. Mercure parted that sea of institutional resistance and created opportunity.”

Given his monumental success in business, it may seem like an unusual move for someone like Mercure to return to academia but not to those who knew him. “I think it was natural for him. He was probably at that time one of the only people who knew how to take a university technology or innovation and translate that into a real business,” said Bryn Rees, associate vice chancellor for research and innovation, and managing director of Venture Partners at CU Boulder. “Nowadays, a lot of people have experience doing that kind of thing, but that just simply didn’t exist back then, and Ball Aerospace was really unprecedented in that way.”

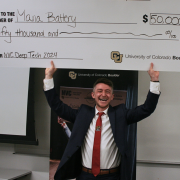

Today, Venture Partners, the successor to CU’s Technology Transfer Office is the commercialization arm of the CU Boulder, Colorado Springs and Denver (Physical Sciences) campuses with a mission to translate research into high-growth ventures and partnerships. It’s now a globally impactful organization helping innovators to bring cutting-edge technologies to the marketplace through tech transfer and startup creation, growth and development.

Recent metrics reflect the success of that approach. CU Boulder now sees roughly 150 inventions per year and nearly 100 license and option deals per year. Additionally, companies working with Venture Partners have raised $2.5 billion in venture capital in the past three years, which contributes to a commercialization program with a $5.2 billion economic impact in Colorado and an $8 billion economic impact nationally.

Still reaching for the sky

When a university startup is created, it is the culmination of years of research and significant work by the founders to build a compelling company vision, strategy and business model. The team at Venture Partners is here to help with each step along the way, including:

- intellectual property (IP) services,

- entrepreneurial training through the I-CorpsTM Hub West,

- a network of industry mentors,

- funding through the Lab Venture Challenge,

- the Ascent Deep Tech Accelerator,

- fast and simple IP licensing through the Licensing with EASE® program,

- and many other resources.

From the pioneering early days of Ball Aerospace and tech transfer at CU, Colorado is now home to more than 500 space-related companies and suppliers including several of the nation’s top aerospace enterprises. “We actually have the largest aerospace population per capita in the nation,” said Chris Muldrow, and CU Boulder continues to be a key player both regionally and internationally.

CU Boulder faculty, staff and students receive about $50 million annually for space research to advance understanding of cutting-edge instruments and spacecraft. Technology has progressed immensely since the days of the Rocket Project, but the spirit of the mission remains much the same today on campus, said Muldrow—to let science drive every mission.

Such work has generated, and will continue to generate, knowledge of the universe that the first UAL physicists could only have dreamed of decades ago. Today, for an astrophysicist like Katie Melbourne, it’s the continuation of a passion for space that began when she was 10 years old. Learning about the universe is something that should be accessible to everyone, she said, “I think it adds immense value to your experience as a human.”

Ball’s legacy of leading the way for researchers to share their innovations with the world is still going strong through Venture Partners, which now supports researchers with many programs including intellectual property management, mentorships, funding opportunities and support, entrepreneurial training and more. What began with Ball has expanded into many sectors and includes over 175 CU Boulder startups such as SomaLogic, Solid Power and newly national brands like Meati Foods (which recently announced a deal with Whole Foods).

“If it wasn’t for companies like Ball Aerospace, we wouldn’t have this whole entrepreneurial ecosystem, this tried and true pathway with the resources you need,” said Rees. “All of that is based on those trailblazers who did it first.”

Note: This publication follows the recent announcement that Ball had reached an agreement in mid-August 2023 to sell its aerospace business to BAE Systems for $5.6 billion.