To Program for Writing and Rhetoric (WRTG) Teaching Associate Professor Rebecca Dickson, maps are an avenue for making a good argument. WRTG regularly partners with the Earth Sciences & Map Library to explore how maps can facilitate new ways of learning for first-year students.

“I tell my first-year students that maps can make a good argument for you,” Dickson said.

Dickson works with the map library to aid in teaching advanced Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) writing classes and recently started using maps for her first-year writing students as well. “I wish I would have started taking them to the map library sooner,” Dickson said. One of the learning goals for her WRTG 1100 students is to see their writing move from description to analysis.

“Most first-year students can describe an object or process in their writing quite well,” Dickson explained. “But analyzing the meaning of something can be very challenging.”

How do maps facilitate writing and critical reasoning skills?

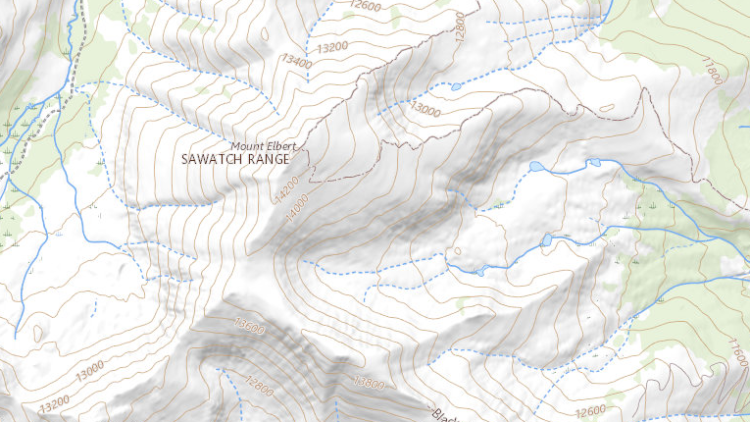

Having climbed every fourteener in Colorado, Dickson loves maps and typically opens her WRTG 1100 classes talking about topographic maps. “Maps can show you where you are and guide you to routes to get to the top of a mountain but sometimes maps are doing something completely different.”

USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer, Mount Elbert https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/topoexplorer/index.html

Physical maps are at once objects and messages. Maps can be described by their physical characteristics and information they provide. They can be further analyzed in terms of what they are trying to communicate and to whom. These are just some of the qualities that make maps excellent subjects to write about.

“It’s a collaborative process,” explained Ilene Raynes, map library program manager. “We meet with a faculty member, study their syllabus and class materials, discuss what kinds of connections they want to make and help facilitate their goals for the class.”

National Geographic, “Diversity of Life” 1999

“We really know our map collection,” added Naomi Heiser, map curator and metadata projects manager. “We’re able to draw on the rich and varied content to curate relevant maps for a given class.”

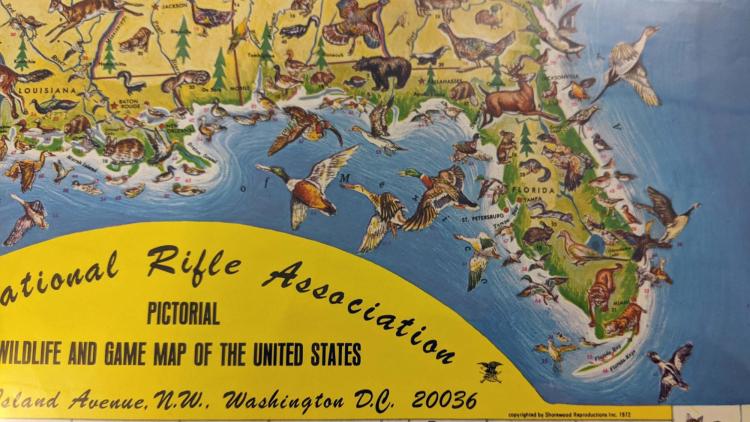

Dickson’s class was invited to view a selection of maps curated by Raynes and Heiser. Of the assembled items, the students were attracted to pictorial maps, particularly those depicting animals. The class gathered around a game and wildlife map by the National Rifle Association. “That got them started,” recalled Dickson.

NRA “Pictorial Wildlife and Game Map of the United States,” 1972

Dickson asked the students to ‘analyze the map,’ building on questions Heiser and Raynes regularly pose to classes: “Who is the intended audience for this map? In what historical context was it made? How does the map project authority? Why does the map exist?”

“They struggled at first,” said Dickson. “Initially, they would repeat the claim that the map appears to be making.” One student suggested that the NRA map depicts animals in the locations where they can be found. Dickson asked if one could realistically use the map as a tool to locate animals to hunt. “No,” she suggested to the class, “Something else is going on here...”

Facilitating communication, post-pandemic

Since the pandemic, many first-year students exhibit a marked reluctance to speak up in class. In the map library, Dickson’s first-year students are asked to form small groups to analyze and discuss selections of one to three maps. Being in smaller groups relieves the pressure to speak before the class and the instructor. Heiser observed, “They relax and engage with each other more freely and we just circulate among them and answer questions as they arise.”

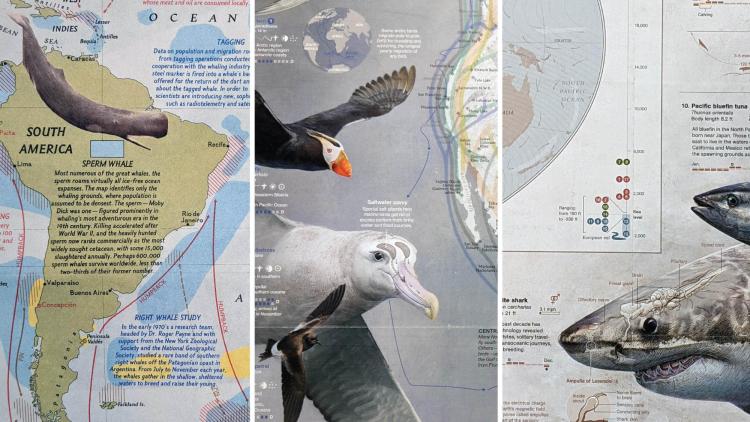

National Geographic: “The Great Whales” 1976; “How Birds Migrate” 2018; “Great Migrations” 2010

One student suggested that while the National Geographic maps depicting the ranges and migratory patterns of whales, birds, fish and sharks contain explicit usable information, they also convey an implicit advocacy for protection and conservation of these animals. Developing the ability to write clearly and convincingly about these kinds of insights is essential.

Descriptive and analytical writing

Students were drawn by the colors and playful depictions of animals in the 1940 illustrated map “The Flora and Fauna of the Pacific.” Dickson noted to the class that the stylistic qualities of the map may have served as a kind of emotional respite from the anxiety surrounding the beginning of World War II and the potential consequences to the peoples and lands in the Pacific Basin specifically.

First-year student Piper Enderlein chose “The Flora and Fauna of the Pacific” as the subject for her final essay. In her introduction, Enderlein writes that the map, “gives us a general education on the different climates and kinds of vegetation of this region, and shows us the most characteristic wildlife of different places through artistically rendered drawings of animals.”

Excerpt from “The Flora and Fauna of the Pacific,” Covarrubias, 1940

Enderlein discovered that the map print was derived from a 15 x 24 foot mural created in 1939 by the artist Miguel Covarrubias for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. “Flora and Fauna of the Pacific” is one of six large murals painted for the exhibition which was collectively titled “Pageant of the Pacific.” Enderlein observes that “This is not the kind of map you would want to use for navigation, but that is okay because navigation is not its purpose.”

‘Planting Seeds’

“I want my students to be more curious at the end of the semester, to ask questions, to realize the world is a lot bigger than they thought when they came in,” Dickson said, recalling the metaphor of scattering seeds in a field. “The teacher may not actually witness the magic moment of learning. Like seeds in a field one has to trust they will germinate each in their own time.”